Ronald John Henry (Ron) Kaulback

(23 Jul 1909 – 2 Oct 1995)

Kaulback, Ronald (Ron) John Henry (1909-1995)

The British explorer, geographer and herpetologist Ronald John Henry Kaulback was born on 23 July 1909 at the Royal Military College in Ontario, Canada, where his father was staff adjutant. He died in Hoarwithy, Herefordshire on 2 October 1995. The family had German origins. In 1922 Ronald's father Henry Kaulback changed his name from 'Kaulbach' to 'Kaulback'.

Kaulback grew up in Richmond in Yorkshire, England, and was educated at Rugby and Pembroke College, Cambridge, where he read History, German and Russian. Initially he wanted to become a diplomat, but was urged by two friends of the family, General Sir Percy Sykes (1867-1945) and General Sir Percy Cox (1864-1937), both Fellows of the Royal Geographic Society, to join the botanist Frank Kingdon-Ward on his next expedition to Tibet.

When Kingdon-Ward asked for his credentials, Kaulback suggested his senior tutor at Pembroke, who wrote: 'I have known Kaulback well through three tumultuous years at this College, and can confidently recommend him to you as an explorer-companion, or as a buccaneer, or probably best of all as president of a South American republic.

Kingdon-Ward, Kaulback and the photographer and cinematographer B.R. Brooks-Carrington (1888-1976), set out in March 1933 and reached Tibet via the Lohit Valley in April. Brooks-Carrington had been added to the expedition at a late stage; his task was to document the expedition with photographs and films in colour. After only three months Kaulback and Brooks-Carrington had to turn at the border of the provinces Zayul and Nagong because their papers were not in order. Kaulback returned with the ailing Brooks-Carrington along another route to Burma, passing over the Diphuk La, a pass between the valley of the Di Chu, a minor tributary of the upper Lohit in Assam and the valley of the Seingkhu, a tributary of the Nam Tamai, which is itself a tributary of the Nmai Hka. He finally reached Fort Hertz (near the village of Putao) in Burma on 24 September.

Kaulback was fascinated by Tibet and in 1935 he organized his own expedition, which lasted from April 1935 to the end of 1936. He was accompanied by John Hanbury-Tracy. Their aim was to find the sources of the Salween and to map its drainage area. They failed to reach the sources due to the tense political situation - Hanbury-Tracy had grown a large beard while on expedition and was suspected of being a Russian spy at some point - but they managed to map a large tract in southeastern Tibet and did some natural history collecting besides.

In 1938-1939 Kaulback spent 18 months hunting for reptiles and amphibians on behalf of the British Museum (Natural History) in the Triangle, the area in Burma between the Nmai Hka and the Mali Hka, two rivers which join to form the Irrawaddy. Though he complained that the area was not as rich in reptiles and amphibians as he had expected, the results were interesting. His specimens contained one new species of snake, Kaulback's lance-headed pit viper (Protobothrops kaulbacki, synonym Trimeresurus kaulbacki) and several other novelties, such as a frog, Rana kaulbacki. Kaulback's correspondent at the Natural History Museum was the herpetologist Hampton Wildman Parker (1897-1968), at the time Assistant Keeper of the Department of Zoology. His collections were described by another herpetologist, the physician Malcolm Arthur Smith (1875-1958). From the correspondence it becomes clear that Kaulback had become quite knowledgeable about reptiles and amphibians.

At the outbreak of WW II Kaulback returned to England where he was commissioned to the Intelligence Corps as an instructor at Netheravon, Wiltshire and in Canada. He asked to be given a chance to see action, and was sent to South-East Asia as a lieutenant-colonel. There, as Officer Commanding Tactical Wing, Kaulback led an intelligence group working in the Lashio area in Burma, behind the Japanese lines. When in 1944 the 14th Army started an offensive, Kaulback's force turned to guerilla warfare and sabotage. By 1945 he had 13,000 Karen tribesmen and 20 British officers under his command; they liquidated 13,500 Japanese soldiers with very little loss on their own side. For his contribution Kaulback was appointed to the Order of the British Empire in1946

When the war was over Kaulback moved to Ardnagashel House on Bantry Bay in County Cork, Ireland, and turned it into a hotel. The botanist Ellen Hutchins (1785-1815) had lived for a few years on the estate where her brothers had planted many exotics; Kaulback added trees and shrubs from the Himalaya. The house was destroyed by fire in 1968, but partially rebuilt in 1969 and housed a restaurant until Kaulback retired in 1974, the year he had a heart attack. Later Kaulback moved to Hoarwithy in Herefordshire, where he lived until his death.

Kaulback was married twice: in 1940 to Audrey [Howard] (1916-1994); they had two daughters and twin sons. They separated in 1976, but the marriage was not officially dissolved until 1984, the year Kaulback married Mrs. Joyce Woolley.

Note. The years of birth and death of Brooks-Carrington vary according to the source. I have not been able to discover anything about the pictures and films shot by Brooks-Carrington while on expedition with Kaulback and Kingdon-Ward.

Click here for his very meagre and underwhelming Wikipedia entry (which I look forward to improving in the near future).

And here for his entry in Who's Who in 1967 (just prior to the Ardnagashel fire). Likewise, here for his entry in the Rugby School Who's Who edition of 1989.

Click the titles for his very detailed and entertaining obituaries in the Daily Telegraph and The Times.

Click here for his biographical details (including his two books Tibetan Trek and Salween) as summarised from his brother Bill's family history The Kaulbacks, and here for a transcript of the diary he kept during his expedition to Burma.

And for a fascinating retrospective dialogue between Ron and Bill also reproduced from The Kaulbacks, click here.

Click Coffeebean the Goat or Losing a Leg, amusing or thought-provoking in turn.

Click here for an unpleasant supernatural encounter of his.

And here for a photographic timeline – not many pictures just yet, but many others will surely emerge in due course.

The Kaulback Collection

Ronald Kaulback in early 1930's

Ronald Kaulback's tangible legacies from his first two expeditions (to Tibet) were his vastly entertaining narratives, Tibetan Trek and Salween, plus the many photographs that he took and the detailed maps that he drew. The books were widely appreciated, of course, but the photographs and maps initially achieved less prominence, as the irruption of the Second World War sent him in new directions. Fortunately, they were eventually rescued from oblivion and presented to the Tibetan Society and the Royal Geographical Society respectively after his death.

The collection of lizards and snakes that he made on his third expedition, to Upper Burma, on which he was initially accompanied by the young zoologist Anthony Howey (later replaced by the geographer Louis Bartholomew), immediately prior to the outbreak of the war, ironically fared rather better. Ron was fortunate to have an opposite number at the Natural History Museum in South Kensington, a Mr Parker, with whom he could correspond (at rather long intervals) and to whom he could dispatch his specimens in the full confidence that they would be made welcome and be fully documented. Please click here for a brief glimpse of their exchanges during the period 1938/39, a window into the trials and triumphs of a specimen-collector in dense jungle surroundings (though note the invariably impeccable typing on his faithful Underwood portable).

The last of these letters on 25 Jul 1939 shows that he was aware of the imminent likelihood of war, and we know that by year's end he was back in England and already commissioned as 2nd Lieutenant, Intelligence Corps. So there would very probably have been quite a backlog of specimens that had little chance of reaching England safely, and were most probably sent to the Indian Museum in Calcutta instead ...

... which explains the existence of a substantial catalogue of his specimens that was published by that institution not long afterwards:

The Amphibians and Reptiles obtained by Mr Ronald Kaulback in Upper Burma, Malcolm A Smith 1, 2 [Department of Zoology, British Museum (Nat Hist), London], Records of the Indian Museum, Vol XLII, Part III, pp 465-486, Calcutta, September 1940 (click here for a local copy)

This publication is still cited today as an important contribution to the ongoing study of Upper Burmese herpetology – as even a casual google will confirm.

And trimeresurus kaulbacki, for example, has its own entry in Wikipedia!

The link en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Protobothrops_kaulbachi redirects to en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Trimeresurus_kaulbacki, alternative systematic classifications for the everyday name of Kaulback's lance-headed pit viper.

Protobothrops kaulbacki / Trimeresurus kaulbacki

He evidently had a special affinity with snakes, having kept a couple of black pit-vipers as pets (they used to cluster inside his shirt, for warmth) back in 1933, and at Ardnagashel in the early 1950's he kept a companionable boa-constrictor by the name of Marmaduke.

When my wife and her sister first moved to London in 1958 to undertake their secretarial training, Ron arranged with the Natural History Museum, hardly a stone's throw from where they were staying, to provide them a private viewing of his collection, in the nethermost region of the building. And in 1996, just a few months after his death, my wife arranged a similar visit for the benefit of myself and our children. Please click here to see some photographs taken on that occasion ... and could that be a specimen of Trimeresurus kaulbacki that she's holding up in picture #4?

We now know (July 2015) that in fact it couldn't and wasn't, thanks to a very interesting and informative contact from an expert in these matters:

Email received from Anita Malhotra (Senior lecturer in ecology and evolutionary genetics at Bangor University), July 2015

I was recently (in June this year) part of an expedition to Arunachal Pradesh in north-east India, which borders both Tibet and Burma, where Protobothrops kaulbacki was found in 2009. Since 2011, Gerry Martin, an Indian herpetologist, has been revisiting the area trying to find a live specimen for venom research. I am happy to report that we did find one this year. Since my return, I have been trying to find out more about Ronald Kaulback, and was eventually directed to your website.

You may be interested to know the answer to your question ("and could that be a specimen of Trimeresurus kaulbacki that she's holding up in picture #4?"). Actually it is not. It definitely has legs and appears to be a juvenile monitor lizard. I have seen the type specimen of Protobothrops kaulbacki at the Natural History Museum in London, and I think it is probably the one in the jar on the left of the upper shelf in picture #1, also seen in picture # 3 (the left of the three complete jars in the picture).

I'd be happy to send you a picture of a live specimen for your website if you are interested (actually, it would be from one of my colleagues on the expedition as I ended up losing the card which had all my photographs on it).

I have an article coming out about the encounter some time this week in The Conversation, entitled "Scientists at work: Tackling India's snakebite problem".

The Third Expedition

Those of you conversant with Ronald (Ron) Kaulback’s background will know that he participated in two expeditions to Tibet in the 1930’s, the first with Frank Kingdon-Ward and the second with John Hanbury-Tracy. He published highly-acclaimed accounts of each – Tibetan Trek and Salween respectively – and indeed Hanbury-Tracy’s own account of the second expedition, Black River of Tibet, was said by some to be even better – high praise indeed.

Kaulback’s third, and final, expedition was to Burma, or Myanmar as it’s nowadays known, and was quite different in nature from the first two. In conjunction with the Natural History Museum in South Kensington, he primarily undertook to collect specimens of previously unknown insects, lizards, snakes, et al, inhabiting the jungle of northern Burma contiguous with Tibet.

He might be thought to have been a curious choice, having read geography and maths in his first year at Cambridge, and thereafter German and Russian. Indeed, on a military mission to Canada in 1942, his immigration record described him as 6’2½”, with grey eyes and fluency in English, French, German, Russian and Tibetan. He was evidently able to absorb and master great quantities of material effortlessly.

To reinforce his own newly-won expertise he recruited a Cambridge graduate in zoology, Anthony Howey, who turned out to be a thoroughly bad choice – lazy, incompetent and seriously deficient in personal hygiene. Why Kaulback chose him is a mystery – P G Wodehouse would doubtless have suggested that he did so to please a dying grandmother. There can have been no other explanation.

Despite his assistant’s shortcomings, Kaulback did accomplish a great deal himself and as described elsewhere he made a considerable contribution to the natural history of the area. Additionally, well-equipped with supplies of antibiotics, and having also trained as a paramedic, he not only attended to the medical welfare of his support-team and porters but also of the villagers en route.

His achievements were cut short by news of the outbreak of WW2 and he hastened home (with his diaries) to join the hostilities. Ironically, as is also described elsewhere, his detailed knowledge of Burmese terrain and tribal loyalties was instrumental in driving back the Japanese invasion and the threat to India.

Kaulback turned his mind to other things after the war, and it was long thought that his Burmese expedition had not been documented (though his zoological specimens had fortunately reached their intended destinations). It was even supposed that he had undertaken the expedition alone, though in fact his assistant had perished in an air crash in 1943. Arising from that mishap, however, I was recently contacted via my website about that luckless individual, and in consequence the diaries have been located.

There are four volumes, all 9½” x 7”, in well-nigh impeccable condition, with marbled covers and reinforced corners. The first three volumes each contain 115 pages (ie sheets) of narrative and the fourth contains 73. They are wonderfully well-stitched, so that they lie flat when open, and scan (or photocopy) without shadowing towards the spine. To somebody like myself, from several generations of book-binders on my mother’s side, they are a joy to handle.

In addition to this textual transcription, there is also a visual scan of every single page of the original diary, which I’m happy to distribute in any convenient medium. It’s not simply a diary of events, however, but an ongoing reflection of a powerful and agile intellect, and might be more accurately described as a journal. Evidently written with an eye towards publication, it is written in the clearest of prose, and the neatest of minuscule.

For some reason or other, Kaulback didn’t number the pages in the diary, and for various other reasons I haven’t either. There is an inevitable mismatch in page-count between the original and the transcription, and this is demarcated in the transcription at every new page in the original. For example, the narrative begins on MS Word p1 with [Vol 1, p001], and continues with [Vol 1, p002] further down MS Word p1, and so on throughout Volume 1, and likewise through the remaining volumes.

But, hallelujah, Bright VA have indexed each calendar date recorded in the original against the MS Word page, and so, with very little difficulty, the two can be tied together.

There is one last issue to be dealt with, and that is the legibility and spelling of the zoological specimens that were collected, or sometimes the place-names of where they were collected. Those that cannot yet be clearly identified, or whose names have been altered by time and chance, are marked as such with “[?]” or even, in severe cases, with “[???]” and will hopefully emerge into daylight sooner or later. The meaning of legible Burmese vernacular, not flagged in any way, can generally be accessed via Google, or is sometimes to be found in the Glossary (to which your own contributions will be very welcome!).

A huge tribute is due to my wife Sonia, Ron Kaulback’s elder daughter, who has done her utmost over the years to keep her father’s legacy properly acknowledged and maintained. For reasons that needn’t be gone into, it has rarely been easy.

And we have been extraordinarily fortunate to have engaged Bright VA Typing Services for this transcription – without their proactive support and professionalism this project would never have got off the ground, or remained airborne.

Please click the appropriate box in the table below:

| Vol 1 | Contents | Transcript | Obscurities | |

| Vol 2 | Contents | Transcript | Obscurities | |

| Vol 3 | Contents | Transcript | Obscurities | |

| Vol 4 | Contents | Transcript | Obscurities | Appendices: |

| Technical | ||||

| Scans | ||||

| Maps | ||||

| Sketches | ||||

| Notables | ||||

| Glossary |

Part of letter received from the Principal Librarian at the Royal Geographical Society in London to Ronald Kaulback's elder daughter, December 2024;

Pictures from the past

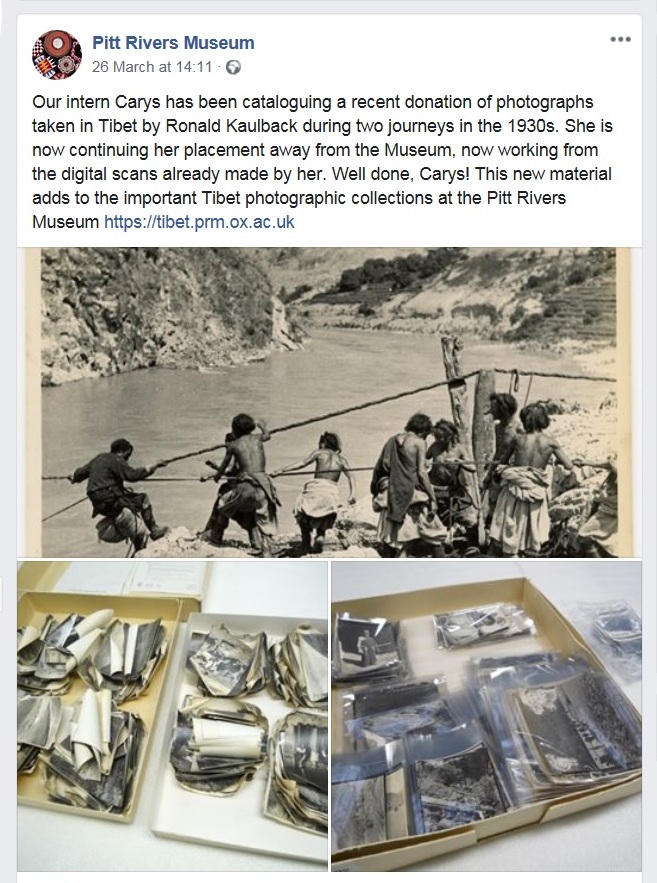

The following Facebook post recently came to my notice, and will be of great interest to all who knew Ron, and those who take an interest in this fascinating part of the world and – alas – its vanishing traditional culture.

The original prints were returned to Ron following the death of his first wife Audrey in 1994, and presented to the Pitt-Rivers Museum last September (2019). They obviously hadn't improved in the passage of time, and one could scarcely believe that they could be salvaged.

But almost miraculously, a great many – maybe all – of them have now been meticulously reconditioned and successfully scanned

as witness the image below

The documentation of the locations and their correlation with his illustrated accounts (Tibetan Trek and Salween) will obviously take quite some time, but that is now no longer of the essence – once begun is half done!

Pictures from the past (Part 2)

It must be borne in mind that, in addition to their subsequent vicissitudes, Ronald Kaulback's own copies of his Tibet and Burma photographs, maps etc, were destroyed when the Luftwaffe bombed his mother's apartment in about 1941 (fortunately she wasn't living there at that time). Other copies existed, of course, with his publishers, or his close family, and after the war was over these were gradually reassembled.

In 1976, when he parted company from his first wife Audrey, he left all such impedimenta behind. When she moved from Ardnagashel to Rossdoon, just up the road from Glengarriff, they moved with her, and were rescued from her boiler-room in 1994 by her executrix, who restored them to Ron (by that time living in England)...

The photographs that have now resurfaced, as described below, are remnants from those other sources – Granny Kaulback and Uncle Bill – who in the course of time passed their personal copies on directly to Sonia.

(Part 2A) A Firswood tranche of Tibet photographs has just (Mar 2020) emerged, less numerous than the museum's, but in relatively excellent condition – and with the bonus of reverse-side annotations (in upper-case) by Ronald Kaulback himself.

Please click here to view the photographs themselves, captioned as per the annotations. Click here for further details.

(Part 2B) Alongside the photographs are a number of what look to my untutored eye like proof copies, photographs of photographs for editorial consideration as regards one or another of his books. However, they're not annotated. I've divided them into landscape and portrait formats, to make for easier viewing.

Please click here to view the uncaptioned photographs themselves.

(Part 2C) Emerging separately (with the album mentioned below) are a dozen or more good-quality geographical pictures, extensively annotated on the back (in lower case) by the man himself. I've sequenced them by the "Photo. No." that he additionally specified (possibly for publication purposes).

Please click here to view the photographs themselves, captioned as per the annotations. Click here for further details.

(Part 2D) I'd guess that this personalised album (helpfully embossed "1933") was arranged and initiated by his mother, known to the rest of us as Granny Kaulback – especially as it is possibly her brother Herbert Townend and his wife Grace who feature prominently on the first page (as per Tibetan Trek, chapter 1). But alas, Ron doesn't seem to have got much further with it!

Please click here to view the uncaptioned photographs themselves.

A family interlude

My wife Sonia and I are very indebted to her wonderfully nice cousin Helen Townend for the following collage of Ronald Kaulback and some of the photographs he took in one or the other of his two expeditions to Tibet in the 1930’s, when all the world was young and optimistic. It’s quite large and slightly overruns the limits of my A3 scanner, but as always I have total confidence in Eboracus to sort things out.

One is obliged these days to self-exculpate for the imperialistic or jingoistic attitudes of generations past. But that was how it was, and modern generations have to get used to that. There is not a major nation in the world today that doesn’t have something to feel uncomfortable or embarrassed about, or ashamed of, in their history, and I’d venture to say that Britain has also more to be proud of than most.

Another historical link in the cutting above is the advertisement for Zam-Buk, a dark-coloured antiseptic cream which came to the rescue, a good few years later, of one Mumtaz Mahal, one of the numerous wives of Shah Jihan, names immediately familiar to Muslim readers – except that in this case Shah Jihan was the cockerel at Ardnagashel and Mumtaz Mahal was one of his hens. But I understand that she was pretty dim, and apt to lay her eggs in the most inhospitable places, and so one day the other hens ganged up on her and pecked-out the top of her head, plus its contents, thereby exposing her entire cranial cavity.

Apparently, this didn’t seem to bother her, and she carried on foraging as usual, but it couldn’t go on like that. And so the empty space up top was plugged with Zam-Buk, which she didn’t seem to mind either, and she lived to a ripe old age (for a hen), though continuing to lay her eggs in the stream.