Obituary1, The Times, Monday, 30 October 1995

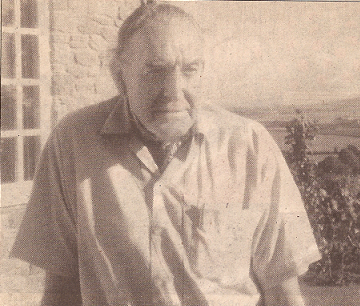

Ronald Kaulback

An explorer in the old-fashioned mould of buccaneering Englishmen who roamed the blank spaces of the map, Ronald Kaulback organised and led expeditions in the 1930s to chart the wildernesses of Tibet.

Cartography was at best a painstaking process in those days and though direction could be accurately monitored, distance could only be estimated by guessing the speed of travel – a hard task in a terrain where mountains towered as high as 22,000 ft and yaks and pack-mules were recalcitrant. But Kaulback was resolute, and during three expeditions he mapped more than 25,000 square miles of the country as well as collecting a medley of rare biological specimens for London's Natural History Museum.

Ronald John Henry Kaulback was brought up near Richmond in Yorkshire. Even as a child he showed an intrepid spirit, ranging the moors from dawn to dusk and, during summer holidays on the northern French coast he would sail out to an uninhabited island and camp there with a band of friends, shooting rabbits and fishing for food.

At school at Rugby he distinguished himself not only on the sports field but also academically and he won a place at Pembroke College, Cambridge, where he read History, German and Russian.

In winter he played [rugby] for the XL Club and the Harlequins, while during the summer vacations he discovered a talent for the balalaika and played with Medvedev's Russian orchestra in various London restaurants.

He was a high-spirited young man, and at times treated university rules with what his senior tutor was once to describe, after a week-long unlicensed defection to Poland, as "a magnificent disregard". Perhaps his best-known prank – one which was to occupy the popular press for some days – was the dunking of a certain Hector Mappin in Grantchester millpond to douse the fire of a quite unacceptable arrogance.

Kaulback's original intention had been to enrol in the Diplomatic Service, but his plans abruptly changed when Sir Percy Sykes and General Sir Percy Cox, both family friends and Fellows of the Royal Geographical Society, urged him to join the famous Himalayan explorer and rhododendron expert Captain Kingdon-Ward on an expedition to Tibet. His senior tutor provided the requisite reference: "I have known Ronald Kaulback well through three tumultuous years at this college, and can confidently recommend him to you either as an explorer, companion, or as a buccaneer or, probably best of all, as president of a South American republic."

Kingdon-Ward and Kaulback set out from India in March 1933 and reached Tibet about a month later. The passes through the mountains were perilous and they and their coolies braved pitiless bandits and fierce blizzards. But they travelled on, covering about 2,500 miles of country and surviving chiefly on corncobs and cucumbers.

Kaulback had to turn back alone after only three months because his papers were not in order, a serious matter in a country which was closed to all but Asiatics. His adventures, however, were not over. On his way back through Assam he came to a village besieged by a man-eating tiger and was implored by residents to kill the beast. Kaulback sat up all night in a machan, a platform built in a tree, with a goat tethered beneath him as bait. When the tiger arrived, and a bleating commotion ensued, Kaulback took aim and wounded the beast but, in the darkness, could not see well enough to finish it off. Only in the half-light of dawn did he climb down from his eyrie and, with brave disregard for personal safety, follow the blood-spattered trail into the forest. He finally encountered the enraged animal in a bamboo brake and mercifully dispatched it with a clean shot through the skull. It was afterwards said to be the largest tiger ever killed in the area.

This and other adventures fired Kaulback's passion for Tibet, and he spent his next six years there. Abandoning his Savile Row suits for native robes, he trekked the gorge country of the Himalayas and sought the source of the Salween river. Conditions were rough, he was plagued by blood-sucking insects and leeches, counting as many as 600 on his body at one time. Once he was bitten by a Russell's viper, whose venom can paralyse the human nervous system in less than an hour, but by putting a tourniquet on his arm Kaulback managed to stanch the flow of poisons through his veins.

Kaulback left his own mark on the fauna of the region too. He was responsible for the discovery of a new species of snake which was named Trimesurus Kaulbacki and, among the five previously unknown species of frog which he collected, one was called Japulari Kaulbacki. He never saw an abominable snowman but once at high altitude saw vast footprints in the snow of a mysterious beast which he believed might be the yeti.

In 1937 Kaulback was awarded the Royal Geographical Society's Murchison Grant in recognition of his valuable contribution to geographical knowledge. However, perhaps the most useful honour bestowed on him was by the Governor of Zayyul who made him a Tibetan nobleman – from then on he was allowed to wear the four-inch turquoise2 earring denoting noble rank and hence to requisition porters and pack-animals for free.

Kaulback's two books describing his exploits, Tibetan Trek (1934) and Salween (1938), went into several editions.

With the outbreak of the Second World War, Kaulback returned immediately to England and was commissioned into the Intelligence Corps. For a short while he was an instructor at the heavy weapons wings of the small arms schools at Netheravon and in Canada. But he was impatient for more active service and in 1943 was promoted to the rank of lieutenant-colonel and posted to South-East Asia.

Here he led an intelligence party working behind the Japanese lines in the Lashio area of Burma. The 13,000 Karen warriors under his command were excellent junglemen and when the Japanese 14th Army began its offensive in 1944 they turned their skills to guerrilla warfare. Kaulback instructed them to bring back the left ear of each enemy killed, rewarding them for each one with five rounds of ammunition. At the final count more than 13,500 Japanese soldiers had been liquidated, though news of VJ-Day took so long to reach Kaulback in the jungle that he and his men were still fighting nearly two months after peace had been declared.

In recognition of his outstanding war record, Kaulback was appointed OBE in 1946. But, like Lawrence of Arabia, he was always to feel pained by the treachery which he felt had been shown to the Karen tribesmen, left after the war in the hands of the Burmese.

In 1946 Kaulback returned to Europe, never to go back to Tibet again. He moved with his family to [an old Anglo-Irish house, Ardnagashel, set on] Bantry Bay in Cork. Successfully turning the large house into a hotel, he presided as a genial host, known for his strong curries and equally potent poteen. But the house was destroyed by fire in 1968, and though Kaulback partially rebuilt it and ran it as a restaurant, he never felt it was quite the same, and shortly afterwards he moved to Hoarwithy in Herefordshire.

He is survived by his second wife Joyce, whom he married in 1984, and by two daughters and twin sons from his first marriage.

Footnotes

| 1: | The material for this Obituary, was evidently provided by Ronald Kaulback's brother Bill, sourced from his survey of the family genealogy:

The Kaulbacks, Lt Col R J A Kaulback DSO MA FRGS, published privately,1979 |

| 2: | The Daily Telegraph obituary has this as amethyst. |