Robert (Robin) Erskine Waddell

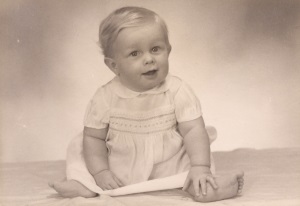

(11 Feb 1945 - 26 Apr 2024)

"Lit by friends Cross Street Chapel, who spoke of how much Robin meant to them, of his kindness, his sense of humour, the way he would listen to everyone without putting his own ideas forward, the way he would always help with anything."

Sunday 28 April 2024

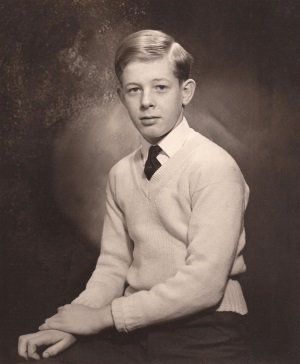

| 1 |

1945 Quorn, Chaveney Road |

| 2 |

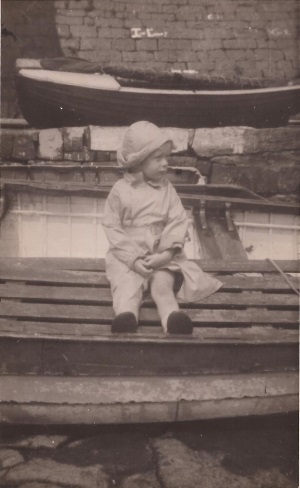

1948 New Quay, Cardiganshire |

| 3 |

1949 Loughborough, 8 Benscliffe Drive |

| 4 |

1950 Pinner, 3 Paines Lane |

| 5 |

1955 London, 25 Cheyne Place |

| 6 |

1958 New passport |

| 7 |

1959 London, 2 Basil Mansions |

| 8 |

1960 Yugoslavia / Croatia, Pakoštane |

| 9 |

1961 Fishbourne, Apuldram Lane |

| 10 |

1962 Nottingham, Fresher |

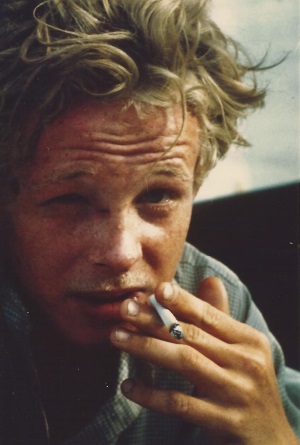

| 11 |

1964 Abu Dhabi, Mangrove swamp |

| 12 |

1964 Sharjah, post-combat |

| 13 |

1967 Belgravia, dummy run for 16 Dec |

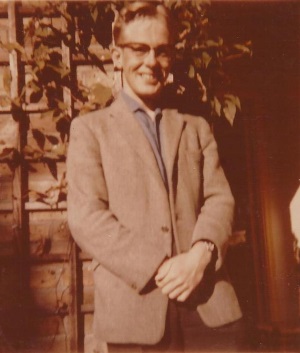

| 14 |

1969 New passport |

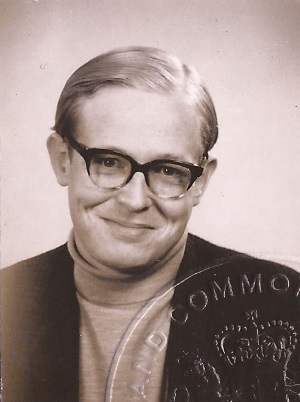

| 15 |

1980 New passport |

| 16 |

1985 Charvil, Fine Fellows |

| 17 |

1986 Thames, festive narrowboat |

| 18 |

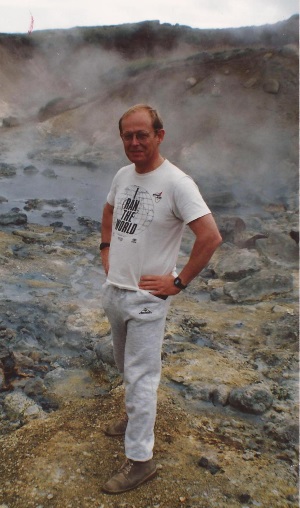

1987 Iceland, Reykyavik Marathon |

| 19 |

1990 Reading, Caversham Bridge |

| 20 |

1996 Aegean, Cyclades Islands |

| 21 |

1997 Reading, by Unitarian Church |

| 22 |

1998 London, Victoria Coach Station |

| 23 |

2000 Majorca, Sunsail charter |

| 24 |

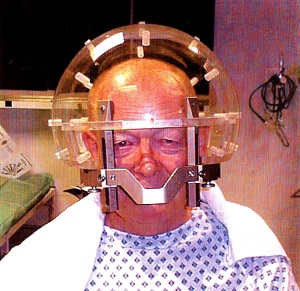

2004 London, Cromwell Hospital |

| 25 |

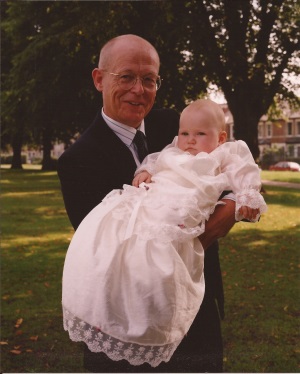

2005 Reading, Shinfield Park |

| 26 |

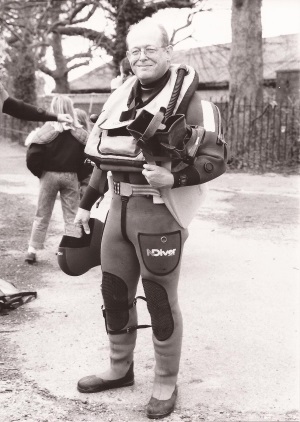

2006 Tobermory, Calico Martlet |

| 27 |

2007, 40 years forsaking all others |

| 28 |

2011 Athens, Acropolis |

| 29 |

2012 Chorlton pre-nuptial |

| 30 |

2013 Victoria BC, Friends MH |

| 31 |

2014 Ireland, Ilnacullin Island |

| 32 |

2015 Mancunia, scruffy selfie |

| 33 |

2016 Gozo, who ate all the pies? |

| 34 |

2016 Mancunia, a surfeit of Robins |

| 35 |

2017 Manchester, Diversely Unitarian |

| 36 |

2018 Manchester, Chorlton Market fun |

| 37 |

2018 Mcr, Sackville Gardens, LGBT Vigil |

| 38 |

2019 Anglesey, "Did you hear what she just said?" |

| 39 |

2020 Ambulance to Wythenshawe A & E |

| 40 |

2020 Mcr, Covid-up |

| 41 |

2021 Afternoon tea at the Midland Hotel |

| 41 |

2022 Manchester: The Movie |

| 42 |

15 Mar 2023 First four treatments now completed. |

| As Samuel Johnson so very nearly said, "Depend upon it, sir, when a man knows he is to hear his prognosis in a fortnight, it concentrates his mind wonderfully." | |

| 43 |

2023 Mcr, blind selfie |

| 44 |

2024 Mcr, Cross Street Chapel |

My personal narrative (ie. a long list of excuses for not having achieved more so far in life) is not yet prepared, but meanwhile, to give some point to this link, you might like to view my photoladder alongside, which runs chronologically from cradle towards grave, and also the following Albums.

Not many pictures of us together whilst growing-up as Simon was consigned to boarding-school 1954-1959.

Picture #1 is unique in being the only (surviving) image that includes both William and Katie. There may have been at least a wedding picture or two, but if so I've never seen one. Another interesting question is who were Simon's godparents? Never ever mentioned.

My own godparents were equally unknown to me during my earlier years. The convention is (or at least was) that a boy should have two godfathers and one godmother, and that, pari passu, a girl should have two godmothers and one godfather. But my parents had only the vaguest idea as to that sort of thing.

Please click here for lurid details.

This entire page might sooner or later be seen as an unauthorised autobiography, and eventually I shall probably have to disown it, amidst a welter of recriminations with myself.

Sturdy little fellow

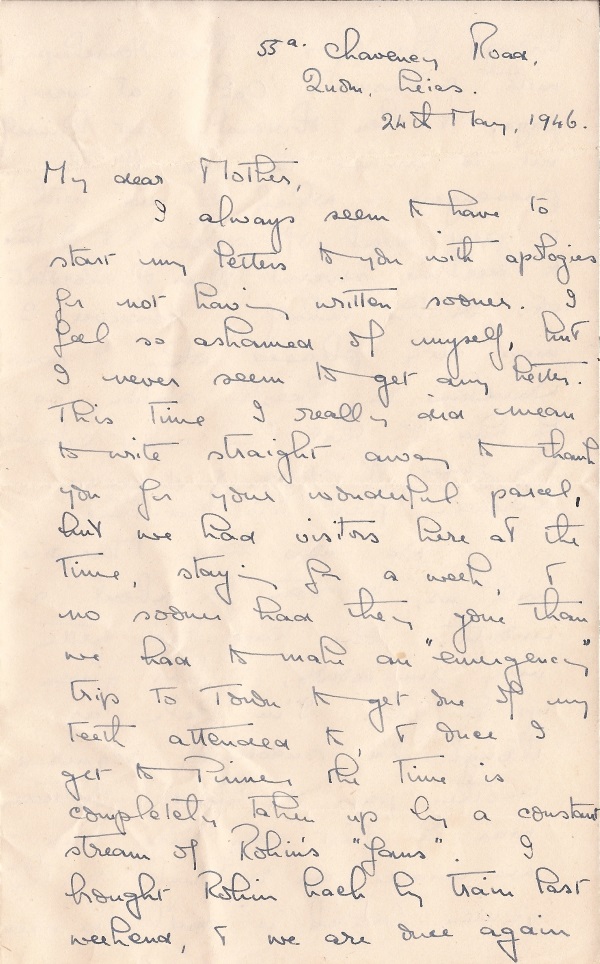

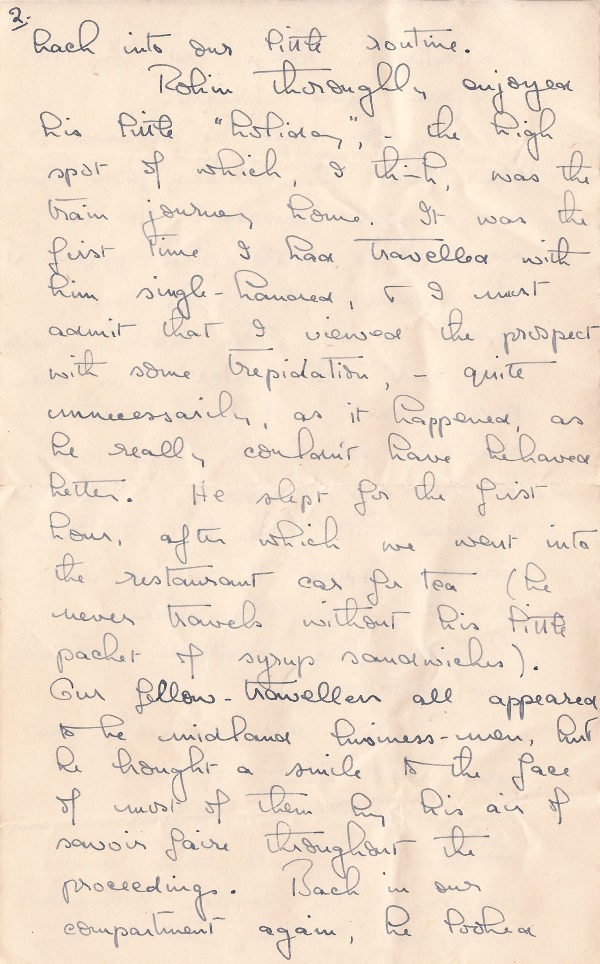

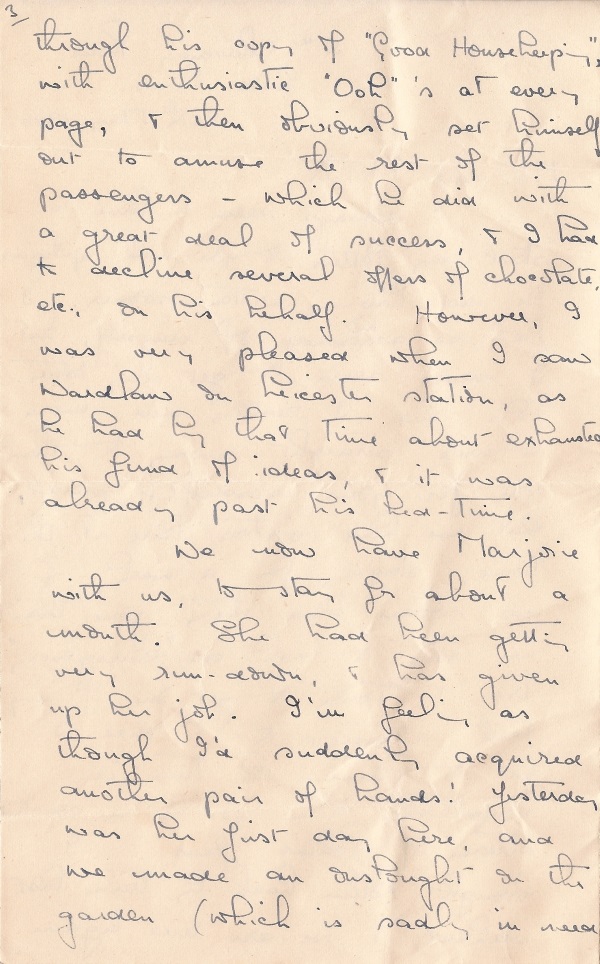

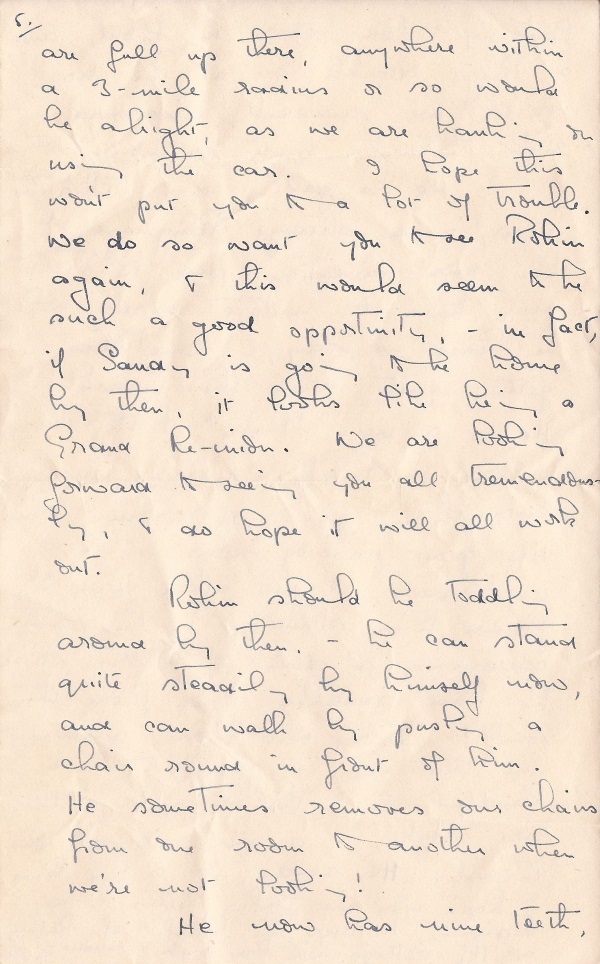

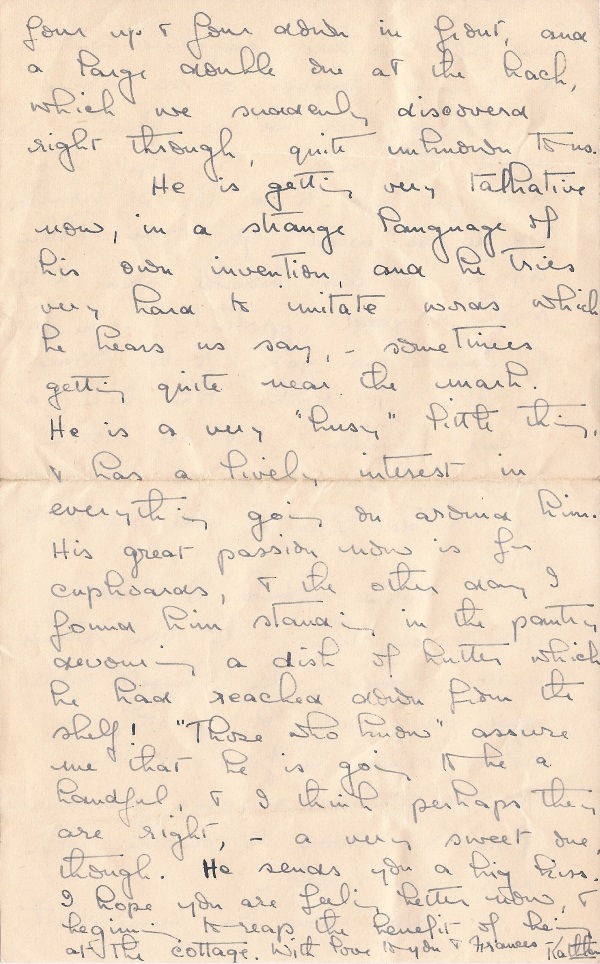

Letter from my mother Katie (Kathleen) to her mother-in-law Hannah Waddell. The remark on p6 shows that Robert and Hannah had by then moved ashore from the Dutch barge to Well Cottage by Birdham Pool.

I've never known quite why my parents were based in rural Leicestershire at that time, but they had been married close by two years earlier so I can only assume that William's war work in the Alan Good engineering empire was the reason.

| Commentary: | |

| p1: | Mother = mother-in-law, and Father = father-in-law, tribal etiquette for young married women at that time, though by no means universal. |

| p1: | Town = London |

| p1: | Pinner = the Blunt briar patch in outer NW London. Think Joan Hunter Dunn. |

| p2: | Syrup sandwiches? How very Paddingtonian of me. |

| p3: | Wardlaw = Walter = Bill = William |

| p3: | Marjorie Blunt = Katie's sister |

| p4: | Lucy Gueritz = William's cousin |

| p4: | Christopher Champion was the son of Ralph and Wynne Champion, Ralph being the New York correspondent of the Daily Mirror and Wynne being one of my godparents, allegedly. |

| p5: | (Uncle) Sandy had been helping to chase the Wehrmacht back to Berlin and was not yet demobilised at the time of writing. |

| p6: | This 'private language' was officially known as Oggly Goggly. |

| p6: | A dish of butter? Butter??? Probably the produce of Alan Good's dairy farm. |

The Knowledge

Like so many children unblessed by a rural upbringing and first-hand witness of what goes on in the farmyard, and without the benefit of modern TV and tabloids (especially The Times), I had virtually no idea about sex, whether for procreation or recreation. Our ignorance was absolutely staggering by the standards of today. We had very little curiosity about reproduction, and indeed our parents were generally loth to enlighten us in any way whatsoever.

But I do remember almost verbatim one very early skirmish on this topic (though I didn't recognise it as such at that time). It was a fine day, and my mother and I were walking down what is now called Old Road from Foxhill to Quarry Hill, where we lived on the Mottram Road out of Stalybridge. I was then about 6 or 7.

A precociously avid reader of my mother's childhood girls' story-books (of the Elsie J Oxenham genre), I'd noticed an obsessive emphasis on the irresponsibility and fecklessness of the Lower Orders – as witness their profusion of barefoot and ragged children - as opposed to the heroines' family backgrounds, often impecunious but always definitely PLU, with a dignified minimum of properly-clad children.

This coincidence had puzzled me, and on a sudden impulse I decided to ask her about it. She improvised the answer that richer people had to spend a lot more money on bringing up their children, and so they had fewer.

Even at that tender age I spotted the fallacy, in that if they were better-off they could obviously afford to provide an appropriate standard of living for numerous progeny.

So I protested, "But parents can't help how many children they have."

She gave me a sidelong glance (65 years later I can still see the scene), as though to assess "where I was coming from", and resorted to her standard close-down, "Little boys shouldn't ask questions."

And so a golden parental opportunity was lost.

At the age of about 12, I was given quite an accurate account of what was involved, by a class-mate called Fishman who was sitting next to me on the coach to games one afternoon. But I couldn't believe that my own parents, for example, could have cooperated in such an implausibly energetic procedure, so (for a while at least), I disbelieved him.

A couple of years or so later, in the small hours of the morning after my father had delivered one of his impromptu tutorials (on the subject of Gresham's Law and the perils of a bimetallic currency), he paused and looked at me quizzically. "That sort of thing's called The Facts of Life," he said. "Have you heard about them?"

"Yes," I replied, rather nonplussed.

"Well, no need to say anything more on the subject," he concluded. And that was it.

Looking back, I think the best summary of the whole business is still Lord Chesterfield's dictum that "The position is ludicrous, the pleasure momentary, and the expense damnable." Caveat amator, and quite possibly amatrix too.

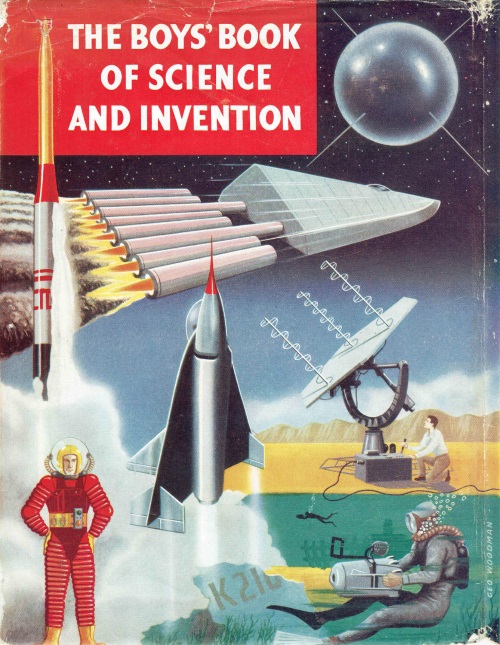

Atomic Ambitions

It was always acutely embarrassing at the beginning of each autumn term at secondary school to have to stand up in class and give your form-master your full name so that he could put it into the register for recording daily attendances for the rest of the school year. I disliked my first name and loathed my middle name. I wasn't at all keen on my surname either, for reasons already mentioned.

In my mid-teens I did try to persuade the rest of the family to call me Robert rather than Robin (which I thought was toe-curlingly sissy), but only my kindly Aunt Helen supported me in this, and after a few months I abandoned the effort. And later in life, particularly since researching the middle name for this very website, I have actually become quite proud of Erskine.

There were two other occasions of similar embarrassment; the first when the maths master in the first year, Mr Sanger, went round the class asking us what our fathers or mothers did for a living. Other boys reported quite normal occupations like being a bus driver, or a postman, or a civil servant, and so on. But I had to say 'industrial adviser', at which he did an exaggerated double-take and got me to elaborate on this bizarre and unheard-of occupation, while the rest of the class sniggered. These days, one could have said management consultant, and Sir would have nodded and moved on immediately.

On the second such occasion, Mr Sanger went round the class asking what we wanted to do for a living ourselves after we left school. Some boys said same as their dads, or various other routine answers. Some said they didn't know, which I should have done. Instead, however I went public on my ambition to be an 'atom scientist'. At this, some of the more easily amused members of the class fell off their chairs with laughter, while the others just chortled derisively.

But it was a sincere answer, and there was more to it than they supposed.

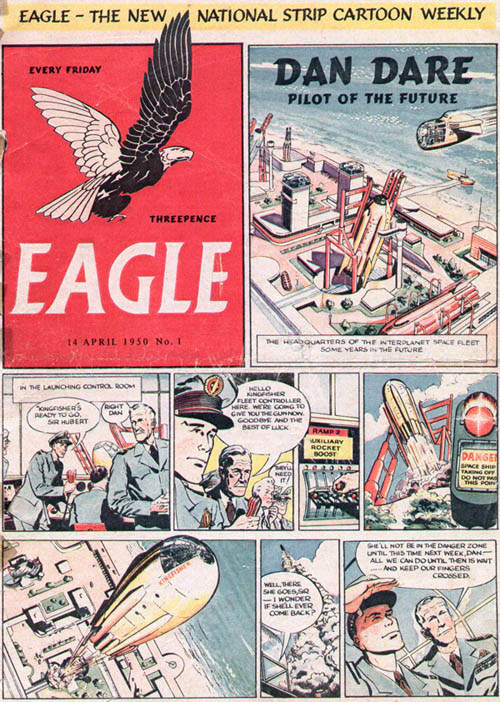

During my years at Kingsmoor School, in Glossop, I became – like quite a few of the other boys – obsessed with space exploration. There were a number of contributory influences, the first of which was the wonderful comic Eagle, its front cover invariably featuring Dan Dare, Pilot of The Future, brilliantly drawn by Frank Hampson.

A year or two later the BBC Light Programme broadcast a weekly space saga called Journey into Space, written by Charles Chilton. This was really powerful stuff, featuring ace British space pilot Jet Morgan, and millions of people tuned in every week for the latest episode. Set in a futuristic 1965, it was totally convincing, and parts of it were seriously frightening (particularly as I was listening to it alone).

At around the same time, the BBC Home Service started broadcasting weekly episodes of The Lost Planet, serialised from the childrens' book written by Angus MacVicar – I'm pretty sure it occupied a slot in Childrens' Hour. It featured a brilliant Scottish spaceship designer cum space pilot, Dr Lachlan McKinnon, and the mysterious frozen world of Hesikos.

It was followed in due course by a series of weekly episodes of Return To The Lost Planet, the second of the six books MacVicar produced on this theme, though I'm not sure whether the others were also adapted for radio.

At that time, the British aerospace industry was still perfectly credible, producing a variety of advanced fighters, long-range V-bombers, and guided missiles, as I well knew from my monthly Meccano Magazine and the weekly centrespreads in Eagle by Frank Hampson. So the idea of British spaceships was not so stupid.

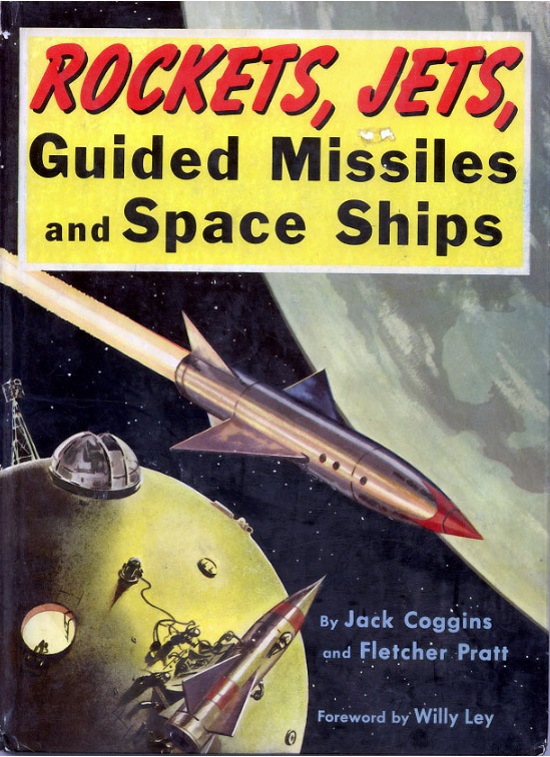

And anyway, one just knew that space-travel capability was merely a matter of time, as it was so brilliantly explained in this classic book, which was my absolute bible. I read and absorbed every single word, and revelled in the diagrams. It was not actually written by Willy Ley, who only provided the foreword, but it still reflected his optimism and clarity of expression.

But then the family removed south, as my father had been working down there for quite some time anyway, and I started at a new school, The Boys' Central, a Church of England primary school in Chichester. Where absolutely nobody was interested in space-travel, and so my earlier ambition to become a space-ship designer withered and died.

At about this time I was given (by whom I can't remember) a book called The Boys' Book of Science and Invention – almost certainly the 1953 edition, rather than the 1959 edition I recently bought via Amazon. However, the all-important chapter titled Secrets of The Atom seems to have changed very little if at all. It gave a really good, straightforward account of the simplest subatomic particles (electrons and nuclei) and the simplest subnuclear particles (protons and neutrons), and introduced the concept of electron shells. It also provided a table of the first 102 chemical elements in order of atomic number (though not with any suggestion as to how this could be organised according to the electron shells of each element).

Its description of positrons, neutrinos and mesons was off-target, but it did say they weren't too important from the chemical or engineering point of view. Positrons and (anti)neutrinos are in fact respectively emitted in β+ and β (both ±) radioactivity, but radioactivity was only touched upon, in the section on atomic power.

But it was enough to fire a lasting ambition (to be an "atom-scientist") that was eventually realised in postgraduate study and postdoctoral research over the period 1967–76. Though, I must hasten to add, in the rather less demanding area of molecular physics, atomic physics tending to imply the really highbrow subnuclear stuff.

Along the way, I had the good fortune to find second-hand copies of really excellent little books on the electronic interpretation of the periodic table, valency (now a rather out-dated concept, I believe), and the application of the simple (G N Lewis) ideas of electronic valency to the structure of organic and inorganic molecules. These were revelations, as nothing of this sort was taught in my London secondary school chemistry lessons! But there was a downside, in that I began to despise the curriculum work, with very adverse effects at A-level and first-year University level.

Particularly good were

- A Simple Guide to Modern Valency Theory; G I Brown, Longman Green, London–New York, 1953. 174 pp

- Electronic Theory and Chemical Reactions: An Elementary Treatment; R W Stott, Longman Green et al London, 1943

and several others that are still in packing-cases.

And there was to be ultimate disillusionment, that the spectacular explicative power of the simple G N Lewis diagrams and the simple certitudes of quantised action provided by the "Old" quantum theory, did not transfer across to the supposed real-deal of "New" quantum theory, better (though misleadingly) known as wave mechanics.

For one thing, the quantum theory taught at undergraduate level was a voodoo hybrid of a variety of competing formalisms, and there was absolutely no attempt at rigour – you just had to learn it in order to parrot it in examinations. It was simply smoke and mirrors.

And indeed, as a postgraduate and postdoctoral student, my disillusion deepened, as it began to appear that quantum theory, even when properly presented, had no explicative power anyway. It had predictive power, of course, in that huge computer programs could accurately calculate the properties (such as energy, and electric and magnetic properties) of atoms and molecules – invaluable to pharmaceutical companies, for example – but it didn't press my humble button as to why atoms combined to form molecules of particular shapes in the first place. When and whither had the concept of valency disappeared? François Villon put it even more poignantly.

I spik you English

I suppose all intending autobiographers have first to decide whether their audience is primarily themselves, to unpick for their own benefit the confusions and contradictions of their lives, or else some section of the general public, to explain and rationalise their actions to best advantage in the distorting mirror of history.

Even mere reminiscencers, such as myself, in the anecdotage of their later years, must make their minds up at some point, and indeed I haven’t yet entirely made up my mind as to which this is to be.

It’s an account of a never-to-be forgotten three-week holiday in Yugoslavia (or Jugoslavia if you prefer) on which my father William took my brother Simon (aged 11) and myself (aged 15) in August 1960. In fact, some of the details are rather hazy and I’m taking this opportunity to try and sort them out, with the benefit of various picture postcards, plus a lengthy letter, that I sent my mother Katie while we were out there on our way home.

For reasons which entirely escape me, Simon and I had to address Katie as Mummie (or refer to her as ‘my mother’) and William as Daddy (or refer to him as ‘my father’), to their dying day, an excruciating embarrassment when our contemporaries simply called their parents, directly or indirectly, Mum and Dad.

In the two preceding years 1958 and 1957, following my parents’ divorce in about 1957, I’d been taken to Switzerland by William’s GP cousins Ryland and Helen Lamberty as a companion to their somewhat younger son John on their summer holiday, but Ryland had a very difficult personality, and in any case Simon had missed out completely.

Please click here to see my letter, addressed from the Park Hotel, Lake Bled, where President Tito’s summer palace was located. The hotel itself, a faded relic of the Austro-Hungarian empire, had certainly see better days.

The letter was signed-off in Austria on our way home soon after 29 Aug 1960 (ie 10 days after the 19 Aug 1960 verdict in the American U2 pilot Gary Powers’ trial in the Soviet Union). A postcard from Simon to Katie is postmarked Bled 3-9-60 which is rather more helpful!

I’ll append a running commentary to support the account in greater detail if possible.

The pre-war kingdom of Yugoslavia had by this time been replaced by a federation of six nominally equal republics, under the benevolent rule of President (Marshall) Tito: Croatia, Montenegro, Serbia, Slovenia, Bosnia and Herzegovina, and Macedonia, though in Serbia the two provinces of Kosovo and Vojvodina were given autonomous status in order to acknowledge the specific interests of Albanians and Magyars, respectively.

Tito (7 May 1892 - 4 May 1980) once remarked "I am the leader of one country which has two alphabets, three languages, four religions, five nationalities, six republics, surrounded by seven neighbours, a country in which live eight ethnic minorities."

[The designations SR (Socialist Republic) and SAP (Socialist Autonomous Province) were discontinued ca 1990]

Simon and I knew nothing of all this, of course, except for the pervasive graffiti proclaiming Živio Tito (Long live Tito), and indeed though William was a didactic amateur historian with a particular interest in the Balkans he managed to stay off-duty for the entire holiday!

The car was a capacious Lagonda DB3 saloon. It was certainly capacious – and easily accommodated the three of us plus a large tubular folding tent. But it suffered from several drawbacks.

After crossing to Ostend, on our first night, in Charleroi (Belgium), we put up at a hotel and ate out at a nearby restaurant – amazingly the couple at the next table were near neighbours of ours in Upper Sloane Street!

Our first night’s camping was in the Dalmatian resort of Opatija aka Rijeka (Croatia) and our inexpert efforts to erect the tent caused hearty derision amongst the German campers alongside. William started bristling at this, but fortunately this didn’t develop into another violent incident!

William’s plan was to drive down the coast road all the way to Dubrovnik, but after several hours on the road next day, we rounded a corner only to discover a cohort of black-shawled peasant women operating an antiquated rock-breaking machine. The map had lied, there was no more highway – time for Plan B!

As you will gather from my letter, Plan B was infinitely better than Plan A would have been, and we spent twelve very happy days camping close by a tiny wayside village called Pakoštane, about 80 km down the coast from Zadar, with Lake Vransko just to the rear.

What was so particularly such fun was that (apparently a widespread practice then and maybe still) the pupils at urban schools would swap premises with children at rural or seaside schools for the summer holidays. That summer, at least, the children in Pakoštane had swapped with those at a school in Banja Luka, in Bosnia Herzegovina, who were in perpetual high spirits from dawn till dusk. Our common languages were O-level German and French, and we all got by very well.

The villagers were very hospitable, especially when they realised we were British, and from time to time, at least so William alleged, a burly character would approach him, making the throat-cutting gesture, and announce “English good, Schwaben no good” – Fitzroy Maclean’s wartime alliance with Tito’s partisans was still greatly admired (though in fact of course he was a Scot!) and the malodorous Schwabs were the Swabian German invaders in April 1941.

Especially helpful was a twenty-something local called Ratko Kupič (or possibly Kupač), who greeted us warmly, showed us around the village, and introduced us to the shopkeepers and of course the old peasant woman. Whenever we thanked him for his assistance, he would wave his hand self-deprecatingly, and repeat his mantra:

“I spik you English, you no spik my language” and was evidently glad of this opportunity to practise.

Simon was intrigued by this, and asked Ratco to say something in Serbo-Croat, such as “Go and jump in a lake”, Ratco obliging with “Idi i skoči u jezero”. Together with “sladoled” Simon felt that would suffice conversationally (as you can see from the back of his postcard to Katie)!

Day succeeded day most happily, but the time eventually came to pack up, strike camp and depart for home. But at some point soon thereafter, quite by chance, we met up with an itinerant Australian, a sort of speedway contestant, competing for prize money. He was doing well enough on the track, but the prize money was in dinars, which couldn’t be taken out of the country.

He was more than willing to unload his winnings in exchange for hard currency, preferably US dollars or UK sterling. William apparently still had a good deal of one or the other tucked into his pocket, a deal was done, the Aussie waved goodbye, and William was left with a heap of dinars, which of course could only be spent on riotous living on a tight timescale.

So, quite possibly as recommended by the biker, we headed for Ljubljana, and Lake Bled in particular, which had a reputation for its expensive lifestyle, being the location of Marshal Tito’s summer palace. And that’s how we came to spend a day or three at the Park Hotel.

Just for the record: on 31 Dec 1993, one US dollar was worth 1,775,998,646,615 Yugoslavian dinars, due to the highest hyperinflation the world has ever seen (313 billion percent).

Tito’s summer palace Vila Bled, a four-square three-storey building faces the island, Blejski Otok, from the shore, but we didn’t really get to do any sightseeing. William didn’t care much for scenery, and was much more interested in the waitress at the hotel, and she quite possibly in him and his Lagonda, obviously very rich English...

Indeed, she accompanied us on a walk through the woodland adjacent to the Park Hotel, and took the opportunity of quizzing me.

“Kein Mutter?” she enquired.

“In England” I parried.

“Krank?” she asked.

“Nein” I said.

“Kommt sie später?” she probed.

“Nicht zusammen” I clarified.

Well gentle reader, what do you think might well have happened later on after lights out.

It was about this time that we all, Simon and William in particular, started to develop huge boils or indeed carbuncles on our necks or shoulders, generally attributed to eating water melon (or unwashed salad), which required antibiotic treatment from Ryland Lamberty on our return.

The common factor of such affliction is of course the involvement of a contaminated water supply, but I don’t think we could hold the old peasant woman to blame for the insufficient hygiene of the village pump. Ryland of course thought that we were to blame for not holidaying in Switzerland!

At about this time too, Simon began a relentless campaign for getting a fishing rod and for having a Salzburger Nockerl. Heaven knows what the origin was of either obsession, but as we headed into Austria the tempo increased relentlessly:

“Daddy, when can I have a fishing rod / Salzburger Nockerl?”

Though he did indeed in due course spend on a fishing rod his arbitraging profits made on sladoled / gelato etc as we moved on from one country to the next, history is silent as to whether he ever caught anything.

But once we arrived in Salzburg, he most certainly did get sat down in front of the most ginormous (one of William’s favourite words) dishful of Salzburger Nockerl. There are of course a variety of recipes on the internet these days, but the image below looks pretty well what confronted him on that fateful occasion, aged just 11.

As the poet Marvell says in another context:

“He nothing did or mean / On that memorable scene”

and weighed in with admirable gusto. Pretty dirndled waitresses giggled as they peeped round the door as the Jungherr methodically demolished the entire dishful. I really rather wished that I’d asked for one too.

Salzburger Nockerl

I have one other enduring memory of our brief stay in Salzburg. I certainly had my wish granted to visit the Mozart Museum, but I can’t recollect any details of it except for the plaster bust that still sits on my desk at this very moment.

It was in fact the chamber concert that same evening in Archbishop Colloredo’s palace, at which immaculately costumed footmen stood impassively throughout, at every pillar of the room, and a string quartet played (inter alia) the Haydn quartet in which one hears, so variously deployed over the past centuries, Gott erhalte Franz den Kaiser. Very odd that nowadays it’s the German national anthem rather than the Austrian one!

Abu Dhabi

The early autumn of 1963 was perhaps one of the nethermost points of my life before or since. I'd systematically messed-up absolutely everything, academic and personal, and there was no obvious way forward.

Then his wise friend and counsellor Daphne Kendall suggested to my father, who was having his own extended crisis at the time, that I could volunteer as chief cook and bottle-washer for a three-month geological survey that was to begin early the following year in Abu Dhabi, involving three postgraduate students from the Royal School of Mines (now the Department of Geology) at Imperial College London. The pay and prospects would be negligible, but it would be a change of scene for me and a great relief to him (especially after the change of government at the General Election on 15 Oct, which he always claimed was the death-knell of his business) as we were scarcely on speaking terms by then.

I was filling in the time by working as a builder's labourer at a renovation in Belgrave Square, and attending a Freudian psychiatrist, a Dr Viktor Frankl, at his consulting room in (I think) Hampstead High Street, once a week. The family doctor Ryland Lamberty had recommended him to my father. There were some fairly comical aspects to these sessions, and I might recount them one day. The principal benefit was being able to talk to a sensible adult without it degenerating into a blame game.

There were two drawbacks to this arrangement, one being the immense amount of travelling (as we lived in Kersfield Road at the top of Putney Hill), and the other being the cost of the appointments, all of which I was having to stump up for after the first few weeks. In retrospect it doesn't sound feasible on wages of £10 a week at most, but then much of what happened during the year that followed doesn't seem credible either, even to me. I think, however, that my father paid the airfare, and probably felt it was good value for money!

The postgraduate students with whom I was going to travel out were Chris Kendall and Paddy Skipwith (both of whom had previous form as regards Persian Gulf expeditions), and a third, Godfrey Butler, was to join us out in Abu Dhabi about ten days later. The first leg of our journey was to be to Rome by BEA, for which, in those days, one checked-in at the West London Air Terminal in Cromwell Road, and took the airport coach out to Heathrow. On that particular afternoon in late December, however, Heathrow was fogbound and we were shuttled back to stay overnight in a central London hotel, which to me seemed very luxurious – and wanting to share the Kingsize comfort, I phoned my on/off girlfriend to join me for some serious Ugandan discussions, the last such get-together for quite some time.

So much for the preliminaries. The events of the next 90 days are chronicled in detail in the diary which I kept of this unprecedented adventure, which was to redirect my life and give me a new sense of purpose. Supreme credit for this should go to Chris Kendall himself, who became my Dutch uncle for the duration of our stay in Abu Dhabi, and later on when we shared a flat in Redcliffe Gardens.

The diary itself is written neatly, almost entirely in ink, and in very small manuscript. It also uses various abbreviations which make it a tough read for the uninitiated. For these reasons, Chris himself very generously arranged earlier this year (2017) for the scanned copy to be transcribed into MS Word, which of course has vastly improved the legibility.

As well as this, I thought an old-fashioned day-by-day table of contents would enable the casual reader to grasp the drift of events more readily – indeed more readily than those us actually involved at the time, for reasons which will unfold.

This online version is very much a work in progress, and will be fine-tuned in due course. At the moment there are just two options.

Plus a parallel narrative, written by Kendall himself in conjunction with the time-line provided by the Complete Diary, but with an eagle's-eye view (at least in retrospect) of what was going on, plus what was not supposed to be going on, together with the background knowledge and perspective provided by his previous expedition to Abu Dhabi in 1962.

I've removed the blocks of photographs that he'd included amidst the text, but these will be reintroduced on separately-linked webpages in due course, insha'Allah. Also, I've suppressed the urge to regularise his sometimes idiosyncratic approach to spelling and syntax!

As for his jovialities about rebellious pugnacity on my part, I'm happy to roll with them – though I'm generally mild-mannered to the point of self-effacement, my hackles do admittedly rise when confronted by what I perceive as high-handed authoritarianism ... on the other hand it is wisely said that he who strikes the first blow has already lost the argument!

Please click as appropriate for overview, military, academic, or appendices.

34 Redcliffe Gardens

- Click here for a StreetMap of the vicinity

- Note IC = Imperial College London, TCD = Trinity College Dublin

In about Feb 1965, I moved out from temporary accommodation in my mother's basement flat in Holland Park Gardens (to both of our great reliefs) to a tiny box-room in the top-floor flat at 34 Redcliffe Gardens SW10 (proprietor a pleasant Australian chap called Russell-Cowan; Bill, a large but dull-witted Pimlican, was his janitorial factotum).

The existing tenants at that time were (as far as I can recall) Chris Kendall 1 (IC postgraduate geologist, ex TCD) in the biggest room (reputedly haunted), Geoff Lemon (ex TCD middleweight fistic phenomenon) in the next biggest (at the back), and Jonah Barrington 1 (ex TCD law undergraduate – but not actually graduate – yet to make his mark in the world of ultra-competitive squash) in the one just smaller than that. The rule was that as each room was vacated the ones with smaller rooms upgraded.

When Chris moved out later in 1965 after getting his IC doctorate and winning a Harkness Fellowship to the USA, and Geoff Lemon moved out for some other reason, Dave Elliott (IC postdoctoral geologist, ex Johns Hopkins) moved into the biggest room, and Wally Johnson (IC geology postgraduate; Jonah always addressed him by his full name, Robert Wallace Johnson, in a bogus American accent) moved in to the back room.

When Wally moved out in 1966, also as a result of getting his IC doctorate and winning a Harkness Fellowship to the USA, Nigel Faulks (a recent law graduate) moved in to the back room.

There had been a sort of interregnum, during which Terry and Gwyneth, a couple of ex art students, moved into the back room for a while. He was tall, bearded and thin, and she was smooth and plump. They lived on social security, and every Friday (benefits day) she would return from the little local supermarket laden with goodies, and start baking biscuits, loaves, and cakes etc, whilst the rest of us stood round sniffing like Bisto Kids at the tantalising aromas. Then they would disappear into the back room for a feast, followed by a noisy coital celebration.

But the day came when their benefits were stopped for some reason, but we allowed them to sleep on the couch on the landing at the top of the stairs, so that the back room could be occupied by somebody more solvent. This gesture was supposedly purely temporary, but weeks passed and Terry and Gwyneth showed no sign of moving out. Worse still, the landing became a no-go area at night for the rest of us – Terry and Gwyneth were making the Beast with Two Backs more or less non-stop through the hours of darkness. No wonder they needed all that carbohydrate.

Jonah solved the problem with typical ingenuity – he solemnly misinformed them one evening that we'd decided (for some unspecified reason) that Bill would shortly be arriving to dispose of the couch, but of course they were welcome to use the floor. They moved out the following day!

Chris and Jonah had between them accumulated a host of friends at TCD, and a good many of them also then in that part of London seemed to regard the top flat at 34 Redcliffe Gardens as a focal point for dropping by, or a gathering point for an evening out (especially with the well-thronged Finch's Wine Bar just a short stroll up the Fulham Road – hard to tell now if it's still there or has been poshed-up beyond all recognition).

Listed below are the ones I remember – not all movers and shakers, one or two not even particularly admirable. They were all in a different age-zone from me anyway, though I became amiably tolerated as an enfant terrible by some of them, or as just terrible by the rest. Possibly interlinked by some strange karma, Chris Kendall and I have remained intermittently, but persistently, in touch ever since – indeed it was briefly in the runes that we would become step-brothers: according to his mother Daphne who rang me after my father died, "he was such a kind, kind man and I would have married him had it not been for his enormous tummy". And they say that love conquers all. Perhaps just as well that it didn't.

- Larry O'Shaughnessy 1 (a life fraught with psychological difficulties)

- Paddy Skipwith 1 (a scion of many lineages, and numerous marriages)

- Nick Tolstoy 1 2 3 (his sister Natasha had, some seven years previously, attended the Catherine Judson Secretarial School at the same time as my future wife Sonia and sister-in-law Susie, and they had been great friends)

But of these, unfortunately, I know nothing further:

- David Cant 1 (who became an officer in the Royal Brunei Navy)

- Dave Elliott 1 ("two l's two t's", tensor virtuoso, died of heart attack in his early 30's)

I particularly remember his catch-phrases- Drop your c*cks and grab your socks, it's daylight in the swamps

- Drop your drawers, here's Santa Claus

- When in doubt, fly to (i, j, k)

- Bryan Hamilton (aspiring wheeler-dealer whose cousin Lois married Dave Elliott)

- Coleman King 1 (genial estate agent) and utterly delightful girlfriend Felicity

- Geoff Lemon (prickly, qualified doctor and Irish Universities boxing champion)

- Jo Xuereb 1 2 (pp 1,2) 3 (softly spoken, courteous, and always immaculately dressed)

Cryptic Crosswords

1 across: What do I do in bed last thing every weekday night, but generally have to finish-off in the bath the following morning?

2 down: And what am I totally unable to manage on Saturday night but achieve triumphantly on the Sunday evening (or at the latest on Monday morning) with the admiring encouragement of my wife?

My what smutty minds you all have. The answers are of course the Times Quick Cryptic crosswords on Monday to Friday, and Times [Cryptic] crossword (competitive strength) on Saturday. Actually they do also publish a Times [Cryptic] crossword (regular strength) on Monday to Friday, but life's too short to tackle those as well.

They also publish General Knowledge ‘times2' crosswords Monday to Saturday, but these are uterly (sic) wet and weedy in comparison.

And on Bank Holidays they publish a Jumbo Crossword, with a 23x23 grid instead of the regular 15x15 size, and two different sets of clues – Cryptic and times2 – with different answers so you can't pick and mix. Ideal if you're confined to bed with flu or somesuch.

Click here for further background.

Innumerable articles and books have been published on the history and practice of cruciverbalism, and I have quite a few of them. However, like the centipede who over-analysed his ability to cope with a hundred legs in unison, and fell over in the ditch, I find that these books inhibit my subconscious nous and I lose the knack$. Other people with far more organised minds than mine have a conscious repertoire of techniques, procedures, algorithms even, and do the entire Saturday competition crossword in 7½ minutes (as I believe M R James, Provost of Eton College, author of the spookiest ghost stories in the language, regularly did). Where's the fun in that?

'The great Russian neuropsychologist Alexander Luria pointed out that identical functions can be achieved by different ensembles of brain areas working together on different occasions. For example, learning a new skill requires conscious, cortical thought. But control may subsequently pass down to sub-cortical centres once the skill is well learnt.

Indeed, consciously thinking about a well-learnt skill may actually disrupt it.'

[I myself have never been able to cope with somebody watching over my shoulder whilst I try to demonstrate - or explain - something I can do perfectly well if left to my own devices.]

The Centipede's Dilemma

Mrs Robin not infrequently quotes the following verse, heard in childhood from her father Ron Kaulback,

A centipede was happy – quite!

Until a toad in fun

Said, "Pray, which leg moves after which?"

This raised her doubts to such a pitch,

She fell exhausted in the ditch

Not knowing how to run.

The effect of over-analysis of a skill is apparently well-known in psychology as "The Centipede's Dilemma".

Newspapers and magazines other than The Times also regularly feature crosswords of similar calibre (notably Private Eye, whose very challenging fortnightly specimen used to be compiled by the notorious Tom Driberg). And The Times itself does publish, every Saturday, the so-called Listener Crossword, of almost legendary impenetrability, complexity, and difficulty, which originated in the BBC companion magazine The Listener; it's not for ordinary mortals such as (possibly) you and certainly I.

The Times also publishes, every Saturday, a crossword in Latin (though the clues themselves are mostly in English), for the benefit of those fortunate enough to have had some educational exposure to the classical languages – those indeed to whom the very word ‘cruciverbalism' has an immediate connection.

The Times cryptic crossword, together with the BBC TV quiz Only Connect, presented by the adorable Victoria Coren-Mitchell, are both evidence of the British genius for quirky general knowledge and lateral thinking. Unfortunately, a precondition for membership of our ruling elite, of either political complexion, is the complete absence of either quality.

But, paradoxically, in everyday life, we cruciverbalists feel distinctly isolated – like dissidents in a repressive despotism – as English society is hostile to any overt evidence of interests other than celebrity, sport and the weather. "Too clever by half" has been the damning indictment against many an emerging public figure. The other cultures of the British Isles – Welsh, Scottish, or Irish – are far more comfortable with such tendencies.

In my own case, on starting work in a new company, one didn't feel entirely comfortable until a sudden sighting of the familiar 15x15 grid on a neighbouring desk at lunchtime betrayed the presence of a fellow enthusiast, even it was only a Guardian ( thank you David Holloway, Ian Carr, Mark Calway and David Jones ...)

So how does a lifelong commitment of this sort begin?

Towards the end of 1959, at the beginning of the sixth-form, I boarded the 52 bus home at Victoria Station, as usual, and headed upstairs, to find a class-mate, David Humphreys, already seated and hunched over the Daily Telegraph. "Wotcher doin' Dave?" I enquired in the patois of that era. "Cryptic crossword", he grunted.

Even years earlier, in the News of the World and the Evening Standard, I'd encountered the general knowledge variety, but this was something new. He showed me the clue he'd just solved, to which the answer was "Love me love my dog", and explained his thought-processes, and said that sort of clue, eg (4,2,4,2,3), was the one he liked best, as it gave away some evidence of its structure.

Verb sap, by some mystic means the whole ethos was revealed – it continues to illuminate my declining years, and, I trust, will keep the neurones fully engaged until the last moment. These days, in my eighth decade, I do appreciate the assistance of the Seiko-Oxford crossword solver to help me with a 12 letter anagram or a particularly tough multiple-word phrase, if all else fails.

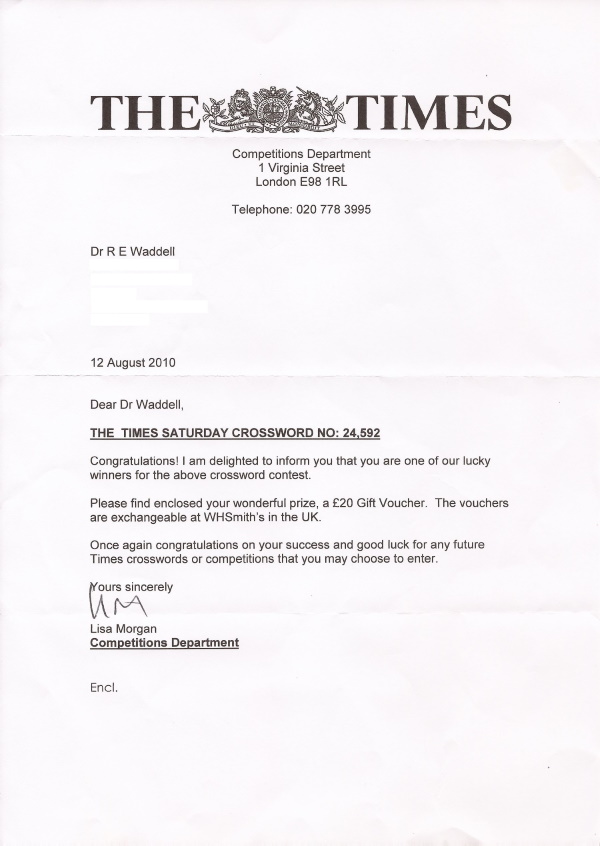

So what benefits accrue? Very occasionally: in my case only thrice have I been one of the lucky weekly winners in the Times weekly cryptic, and twice in the Independent, so in sixty years I've scooped £100 in gift-tokens. And as you can see [Jan 2020], it's been a barren decade since the previous bonanza ...

It's not an ego-trip either; after cracking a particularly difficult clue, my admiration is always for the ingenuity of the setter (aka compiler) rather than any feeling of cleverness myself. I have the same attitude towards the Universe, which I see as a gigantic crossword set by some Great Compiler to beguile us.

And although the feats of the truly stellar crossworders who take part in the Times Crossword Championships1, 2 every year are way beyond the reach of us honest plodders, at least we're all on the same track – but just that they're much quicker – rather like we're way back in the pack of the London Marathon while the Kipchoge's battle for top place.

In bygone days Roy Dean, and then John Sykes (a particularly astonishing individual), was the magister magistrorum, but now Mark Goodliffe (even more remarkable for the breadth of his capabilities) is the one to beat – even if he very occasionally goes off-piste.

So where when and how did all this begin?

Secret history of the crossword: Why Her Majesty fills one out with her kippers and how the puzzles helped crack the Enigma code

By Alan Connor

27 December 2013

‘One of those fads that people will tire of in six months,’ people said when crosswords were invented 100 years ago. A huge misjudgment, of course. The first newspaper crossword appeared in December 1913 — devised by Liverpudlian Arthur Wynne for the Christmas edition of the New York World. Wynne told his bosses to patent the idea; they declined. Here, ALAN CONNOR reveals some fascinating facts about this popular pastime...

Colin Dexter, creator of Inspector Morse, named the Oxford-based detective, his sergeant, Lewis, and many of the suspects they investigated after people who kept beating him in crossword competitions.

In 1941, solvers of the [Daily] Telegraph crossword were invited to enter a competition. Those who were successful were asked to join the codebreakers at Bletchley Park.

The last thing George VI did before he died in his sleep in 1952 was to complete a late-evening crossword.

Crosswords were at first dismissed as a useless pastime, but some of the people who cracked the German Enigma code during the Second World War were there through a crossword contest

One of Britain’s first cryptic setters was Adrian Bell, father of the ex-BBC war reporter and former MP Martin Bell. He is remembered for gems including ‘This cylinder is jammed (5, 4)’ for SWISS ROLL and ‘Die of cold (3,4)’ for ICE CUBE. His puzzles proved popular with politicians, who wrote to the papers with their solving times. ‘It made you wonder what they did in their Cabinet meetings, to tell you the truth,’ remarked Bell.

As Provost of Eton College, ghost story writer M.R. James was said to have cooked his breakfast egg for as long as it took him to complete the cryptic crossword. He did not like a hard-boiled egg. Similarly, the Queen was said to have begun her day with a crossword at breakfast.

Crosswords were so popular among U.S. commuters in the 1920s that the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad provided dictionaries for passengers.

In 1944, MI5 noticed the [Daily] Telegraph crossword[s] contained answers including OMAHA, MULBERRY, NEPTUNE and OVERLORD — all top-secret codewords for the impending D-Day invasion. They interrogated the setter, a teacher, and concluded it was a coincidence [I cannot believe this].

The Queen’s working day, according to Vanity Fair magazine, starts at 8am with kippers or kidneys with toast — and a crossword puzzle before the Bagpiper to the Sovereign begins to play.

Stephen Sondheim and Leonard Bernstein took longer than planned to complete the musical West Side Story because every Thursday they downed pens to solve fiendishly difficult crosswords from the BBC magazine The Listener.

The crossword editor of Country Life magazine suspected a hoax when the signature of a winning entry was that of Princess Margaret. One call to Buckingham Palace uncovered the truth, and the three guinea prize was duly dispatched.

The word ‘clue’ originally meant a ball of wool. Because balls of wool were helpful for finding your way out of a maze, the word came to mean anything that gives a helpful hint.

When crosswords appeared in Britain, The Times insisted the puzzle was ‘making devastating inroads on the working hours of every rank of society’, before deciding to print its own.

When Stephen Fry was sent to prison for credit-card fraud as a teenager, his mother would visit him and pass him crosswords, cut from newspapers, under the glass.

Poet W.H. Auden complained about the low standards of U.S. puzzles. ‘The clues in British crosswords may be more complicated,’ he insisted, ‘but they are always fair.’

Brain: When Stephen Fry was jailed as a teenager, his mother passed crosswords to him in prison

John Sykes, a champion crossword solver, used to start in the bottom right-hand corner of a crossword, on the basis that the setter may have written those clues last, in a more tired frame of mind.

Castaways on Desert Island Discs who have asked for crosswords as their luxury include dancer Lionel Blair, footballer Trevor Brooking and actors Simon Russell Beale and John Gielgud. Gielgud amazed actors by the speed with which he could finish crosswords. A cast member looked at one completed grid and asked what the word DIDDYBUMS meant. ‘No idea,’ replied Sir John. ‘But it does fit awfully well.’

Frank Sinatra wrote a fan letter to the New York Times, giving his solving times, and remarking: ‘What a wonderful way to pass the time and also learn new answers every day.’

Satirical magazine Private Eye’s crossword is legendarily smutty. One especially scatalogical puzzle, in 1972, was set by the notoriously debauched MP Tom Driberg. The £2 prize was won by Mrs Rosalind Runcie, whose husband was then the Bishop of St Albans and later the Archbishop of Canterbury.

- Two Girls, One On Each Knee: The Puzzling, Playful World Of The Crossword by Alan Connor (Particular Books, £12.99).

[Spoiler: The answer is ‘Patella’]

- How To Do The Times Crossword by Brian Greer (Times Books, 2001)

In a rather random way over the past three years or so, I’ve collected a few completed Times Saturday crosswords for a purpose such as this, and so please click here to see them.

Alas, my focus on the website and the numerous encroachments of ill health have meant that I might not be able to explain these myself any more, but you are very welcome to try them and I might just still be able to help!

Sex and smoking

Many and varied are the forms of what the Book of Common Prayer (the last time I looked) refers to rather briefly in an Aunt-like way as the “natural affections and desires” (very few of which I’m at all conversant with) and I don’t think it says much about tobacco either, or alcohol.

Tobacco is the new kid on the block (just half a millennium) whereas alcohol has a pedigree almost as old as humanity. Paradoxically, smoking is looked upon more kindly by ones aunts – and certainly less censoriously by Salvation Army ladies – than drinking would be. So one saw a stronger social acceptance of tobacco than alcohol.

Smoking, however, is now widely banned indoors and drinking is conversely now widely banned out of doors. Either way, social occasions are all the more difficult for those of us who are naturally inhibited and find that the offer of a glass or a cigarette are ideal ways of making acquaintance.

As regards the natural affections and desires in general, I would rather accept somebody as they reveal themselves in conversation about current events, for example (and if they’re British so much the easier), than hear anything more personal about them, let alone their sexuality, gender reassignments, nasty experiences in the woodshed as children, and so on. And I have nothing but contempt for women who try to monetise sexual situations that happened years, or even decades, ago. Like you probably, I too was sexually propositioned, often rather dramatically, a certain number of times over the years, and in the majority of cases the predator was female, almost invariably rather older than me. Why, I don’t know, and in almost all cases I evaded the situation, most probably to avoid any possibility of commitment. Now I look back, of course, I rather regret most of those lost opportunities!

Lord Chesterfield observed that the pleasure is momentary, the position ridiculous, and the expense damnable. I notice he puts position in the singular, though Greek vases and Roman mosaics reveal a variety of options, of course. Oscar Wilde stepped in, as always, to say, that “A cigarette is the perfect type of a perfect pleasure. It is exquisite, and it leaves one unsatisfied. What more can one want?”. And it was of course Rudyard Kipling who penned the immortal line

“A woman is only a woman, but a good cigar’s a smoke”

My father-in-law Ron Kaulback, an expert on all such matters, sometimes recalled the definitive Pathan proverb

A girl for duty,

A boy for pleasure,

But a goat for real delight!

And there I’d better leave it, with one rather good joke on the topic:

A young man, newly married, asks his father about difficulties on the intimate side of things. His father advises him to use plenty of vaseline, and in the event of further difficulty to use even more. Some days later the young man returns home to find his wife enjoying a cheap cigar, so he rushes back to say “Dad, she’s smoking”, and the father tells him, “Son, I told you to use more vaseline!”.