Professor Douglas Shearman

Unorthodox and inspiring geologist

Peter Bush

Thursday 22 May 2003

Douglas James Shearman, geologist: born Isleworth, Middlesex 2 July 1918; Assistant Lecturer, Imperial College, London 1949-51, Lecturer 1951-63, Senior Lecturer 1963-71, Reader 1971-78, Professor of Sedimentology 1978-83 (Emeritus); married 1949 Maureen Pugsley (two sons, one daughter); died Cassington, Oxfordshire 12 May 2003.

During his long career as a geologist at Imperial College, London, Douglas Shearman was a charismatic, enthusiastic, dedicated and unorthodox teacher and research worker. His lectures and seminars, illustrated by his own elegant and explicit diagrams, were stimulating and exciting. His view, now deeply unfashionable, was that it was his responsibility to show students how to think and not to fill their minds with endless details. Staff and students alike regarded him with admiration and affection, even those staff whose forms he failed to fill.

When Shearman was presented in 1984 with the Lyell Medal of the Geological Society by the President, Professor Janet Watson, she summed up his research genius: “Two aspects of your scientific personality stand out. One is your genuine delight in a new idea and the way in which such an idea tends to dominate your thoughts to the exclusion of all else - the second, your ability to look at some very simple phenomenon which others have taken for granted and find something new in it."

After a primary education in Hounslow, west London, Shearman moved with his parents to Southend, where he completed his school education and, importantly, spent many hours exploring the Thames estuary and Essex marshes. After school he joined the Post Office as a trainee engineer. However his career was short-lived because in 1939 he was recruited into the Royal Navy. During his basic training in Dover he met in the Naafi Tom Pain, a young soldier who was examining a fossil from the chalk using a hand lens. Discussions over tea and doughnuts set Shearman on a career in geology.

After the Second World War, much of which was spent as a wireless operator on a minesweeper in the North Atlantic, keeping the lanes clear for the Russian convoys, chance played another trick. Shearman went to live in Chelsea and heard that at Chelsea Polytechnic there was a course in geology. He enrolled in 1946 and came under the influence of William Fleet, a remarkable and inspiring geologist who taught all the courses and ran all the field excursions. Shearman was awarded a first class degree and appointed Assistant Lecturer at Imperial College by H.H. Read.

Read, who recognised that the study of sedimentary rocks was becoming increasingly important, called Shearman in and said, "We need someone to work on and teach about sedimentary rocks, and I have chosen you." So Shearman became leader of the Sedimentary Subsection (initially of one), a post he retained until he retired in 1983.

Doug Shearman's research interests were very varied. They frequently resulted from a new look at an old problem or the connecting of two apparently unconnected phenomena. A big advantage he had was his ability to remember practically everything he read or saw. He would, for example, refer to a paper published in an obscure journal some 30 years earlier which was absolutely relevant. The downside of his ability was his tendency not to label any samples he collected or any photographs he took until they were required for publication.

During the late 1950s and early 1960s two major areas of research developed in the Sedimentology group under Shearman's direction. The first was a study of the limestones and dolomites found in the French Jura. Here Brian Evamy and Shearman developed micro-chemical staining techniques which helped unlock the cementation history of limestones, and Shearman, with other students, used trace element and other methods to elucidate the processes of dolomitisation and dedolomitisation of limestones. These techniques have since been used worldwide. The second area of research was on the inter-tidal sediments of the Wash on the east coast which was initiated by Graham Evans.

When the study of modern inter-tidal/supra-tidal sediment deposition was transferred to the arid environment of the Trucial Coast of the Arabian Gulf (now the United Arab Emirates), Shearman, Evans and their co-researchers defined what was to be called the Sabkha environment, and recorded the first example of Recent anhydrite. This study, together with one Shearman made in Baja California on inter-tidal laminated halite (salt) deposits, allowed him, working with John Fuller in Canada and others around the world, to re-interpret ancient evaporite sequences with great benefit to the oil industry.

In recognition of his work in sedimentology, Shearman was awarded a DSc and personal Chair in Sedimentology (the first in the country).

Graham Evans

It's rather presumptuous of me to embark on this, but one just wants to capture a flavour of the man for present purposes. I only met him once or twice; he was very pleasant and I can well believe he was a very fast-track academic, being at that time a youthful Senior Lecturer in the Department of Geology (the erstwhile Royal School of Mines) at Imperial College London.

As an early explorer of Abu Dhabi's geological potential, he was of course the Godfather of subsequent expeditions, and it was he who soothed all the hurt feelings during his brief visit in early 1964, following the bizarre allegations made against us.

As attested by the internet, he has also become a crusader (probably the wrong word these days) for the sanctity and preservation of Abu Dhabi's sabkha, a holy and enchanted relic of Arabia's ancient geology that has been encroached upon by urban sprawl.

UK scientist leads fight to save capital's sabkhas

In 1962, Graham Evans of Imperial College, London was the first to document the significance of Abu Dhabi's sabkhas – salt flats that are "unique in the world" and could be a gauge of global warming.

Vesela Todorova

November 21, 2010

Abu Dhabi's salt flats form in a few areas, including on the road towards Liwa. Many people do not know what a sabkha is. Even fewer, if they saw one, would find it beautiful and worth protecting.

But sabkhas, as the low-lying coastal salt flats along Abu Dhabi's western shores are called, were making the emirate famous long before any of its man-made attractions. Ask a geologist anywhere about the UAE's capital and they will immediately recall Abu Dhabi's sabkhas - which are the largest in the world.

Among the sabkhas' most ardent supporters is Prof Graham Evans, a professor emeritus at Imperial College, London. Prof Evans has been studying Abu Dhabi's sabkhas since the early 1960s and visited again this month. He was accompanied by his associate Dr Tony Kirkham, who has been campaigning on behalf of the sabkhas since the mid-1990s.

Their goal: to raise concern among anyone who will listen. A surge in development means the sabkhas are quickly disappearing and with them Abu Dhabi's ownership of a piece of nature that could help unlock mysteries about ancient sea levels.

"We have seen what has been going on and we feel horrified," said Prof Evans. "For the past 10 years, we have been trying to persuade the Government and various agencies that this [seemingly] rather uninteresting salty plain is unique in the world and they should preserve it."

The sabkhas lie along the coastline west of Abu Dhabi city, stretching all the way to its western-most parts. They extend up to 15 kilometres inland.

Their harsh beauty will evade those observing them from the comfort of a car. A closer look is required to appreciate the large expanses of salty crusts, forming various shapes. In winter, the surface is flooded with rainwater. In drier months, as the water evaporates, the crust cracks into almost symmetrical polygon forms. In other areas, there are whitish wrinkles, created by tiny organisms.

Because of the high salinity and the hard crust, plants do not grow on the sabkhas. The salinity makes them inhospitable for animals too. Cynobacteria, however, are able to thrive. They form large patches on the sabkha surface.

When Prof Evans arrived in Abu Dhabi in 1962, he found unspoiled stretches of sabkha that yielded discoveries with world-wide significance. By 1996, when Dr Kirkham was living in Abu Dhabi, the original sabkhas studied by his former tutor and his colleagues had been spoiled by human activity.

Dr Kirkham identified three areas of exceptional significance and lobbied for them to be protected. They are along a 30km stretch of coastline in Al Dabbiya, approximately an hour's drive from Abu Dhabi city. The scientists think it is not too late to protect them today.

"There are roads and pipelines, but it is still reasonably well-preserved," Dr Kirkham said.

Civil work and oil and gas infrastructure projects, dredging and infilling are the main threats. The industrial area of Musaffah is a typical example.

Dr Thabit Zahran al Abdessalaam, the director of the biodiversity sector at the Environment Agency - Abu Dhabi, agreed that saving at least some of the sabkhas should be a priority.

"It is something we need to look into seriously, and at the present moment we are not," he said.

"It is an issue of awareness and we scientists are to blame," he said, explaining that a parallel can be drawn with the ways mangroves were regarded here in the past.

Not so long ago, mangroves were considered useless swamps and were destroyed. Now, their conservation profile is a lot higher and there are many efforts to protect or replant them.

Sabkhas are part of a living system which includes some of Abu Dhabi's off-shore islands, its shallow sea lagoons and coral reefs. A vivid description of the dynamics that formed the sabkhas is presented in the book The Emirates – A Natural History.

Sabkhas form close to seas as the salts produced by coral reefs are deposited on land. In the summer months, water evaporates and a hard crust of calcium carbonate gypsum and other salts forms just below the surface. This crust prevents plants from settling on the sabkhas and it also ensures they are flooded by rains. As the rainwater cannot seep into the ground, it slowly evaporates, forming the sabkhas' unique crust.

Prof Evans believes that explaining the processes forming Abu Dhabi's sabkhas can be done by a museum, which could turn them into a natural history attraction.

And the sabkhas still have a role in science. This month, Prof Evans and Dr Kirkham collected 20 samples from hills of ancient origin, dotted around the sabkha surface.

They are looking for funding to enable them to date the newly collected samples. The information, they said, will yield important details about past periods of sea level rise - and could provide a yardstick for global warming.

The first adventure: his arrival

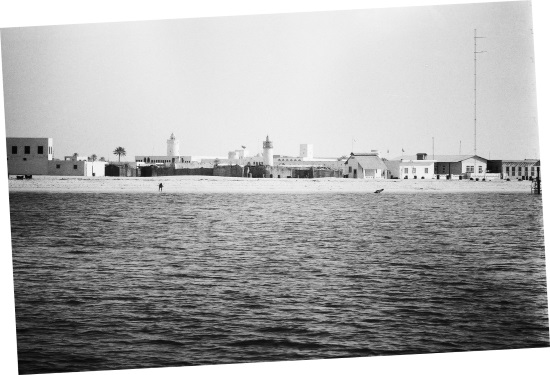

The story of how Graham Evans arrived in Abu Dhabi is like something from an adventure book.

He was brought in by the British Royal Navy, one of the few transport options in the autumn of 1962.

He camped on Saadiyat Island with two research students, plus an Omani guard, a camel and a cat which "appeared from nowhere".

His wife was also there, as the couple were supposed to be on their honeymoon.

"There was just dates, fish and tinned food," said Prof Evans, remembering how his young bride had tears in her eyes once, when after a visit to the market, he appeared with an onion and a head of lettuce.

"The fort," he added, "was the biggest building in town."

His research team also got unwanted attention after the research students were lost at sea and spent the night in a boat during a storm.

Yet, the expedition was to yield a discovery which "caused an enormous stir in the geological world".

Exploring sites on Saadiyat and Musaffah, Prof Evans discovered that the mineral anhydrite was forming just below the sabkha surface.

"This mineral is common on the geological column as a cap rock in oil fields, in successions of carbonate rocks all over the world," Prof Evans said.

"It was always assumed it was formed in deep water."

But in Abu Dhabi it was formed in coastal flats, which were flooded by some water, but only occasionally.

"This is now in geological textbooks all over the world," Prof Evans said.

vtodorova@thenational.ae

Sabkha Workshop

– Abu Dhabi

Sunday 14th March 2004

The Abu Dhabi Islands Archaeological Survey (ADIAS), in collaboration with the Environmental Research and Wildlife Development Agency (ERWDA), is pleased to announce that on Sunday 14th March 2004 there will be a half day workshop on The Abu Dhabi Sabkha.

The Seminar will be held in the 3rd Floor Seminar Room in the ERWDA HQ building, Abu Dhabi. Time: 10.30 a.m. – 1.30 p.m.

We are extremely fortunate to have two distinguished speakers who are the world experts on the Abu Dhabi sabkha:

Professor Graham Evans

Graham Evans is an Honorary Professor of Sedimentology at the Department of Ocean and Earth Sciences, University of Southampton; Emeritus Reader in Sedimentology, University of London; and Honorary Associate Professor of Sedimentology, University of Nanjing, China. Graham received a BSc in Geology from Bristol University in 1956 and obtained his PhD in 1960 at Imperial College, London. He has taught and supervised many research students and has been involved in sedimentological research in the Arabian Gulf, Northwest Europe, Spain, Turkey and India. While at Imperial College Graham began studies in the Arabian Gulf. He was Associate Professor and UNESCO consultant at the Marine Institute of METU, Ankara, Turkey from 1978 to 1979, and visiting Professor with the Universidad Complutense Madrid and University of Vigo, Spain between 1991 and 1992. Although Graham now lives in Jersey he continues to work in the United Arab Emirates, Spain and Turkey on sedimentological/archaeological problems.

Dr Anthony (Tony) Kirkham

email: tony.kirkham@

technoguiide.com

and kirkhama@

compuserve.com

Tony Kirkham was employed by BP Exploration for 20 years as a Sedimentologist and Senior Development Geologist. He mostly worked within reservoir engineering teams on international development projects and had long-term assignments in Norway, Egypt and Turkey. From 1994 to early 1997, Anthony worked as a Geological Specialist with Abu Dhabi Company for Onshore Oil Operations (ADCO). He then became a Senior Technical Consultant with Landmark Graphics in Abu Dhabi, followed by Manager of Reservoir Characterization, Research and Consulting, Inc. (RC)2 with responsibility for Europe, Middle East and Africa. In late 2001 Tony joined Technoguide as Manager of Consulting Services. He received his BSc. from Aberystwyth University in 1970. MSc from Imperial College, London in 1972 and PhD from Bristol University in 1977. Sedimentology, reservoir characterisation and 3-D reservoir modeling are his particular areas of interest. Tony is a member of the Editorial Advisory Board of Geo Arabia.

Graham Evans had made the first IC expedition to Abu Dhabi in 1961, in company with Doug Shearman and (possibly) David Kinsman. Indeed it was Shearman who introduced the word "sabkha" into the geographical lexicon.

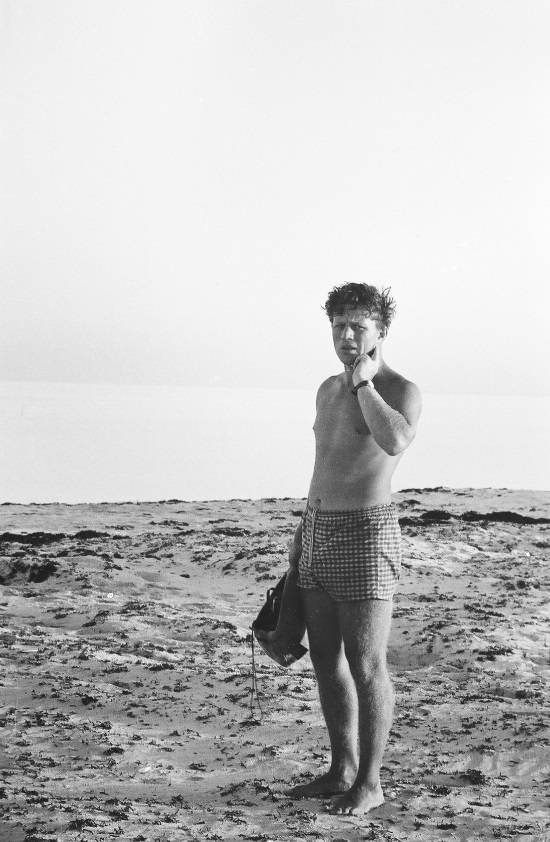

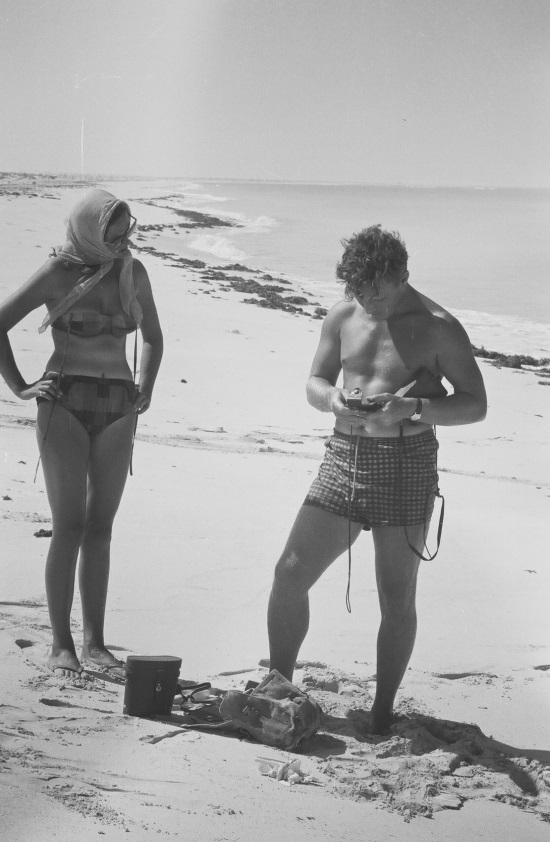

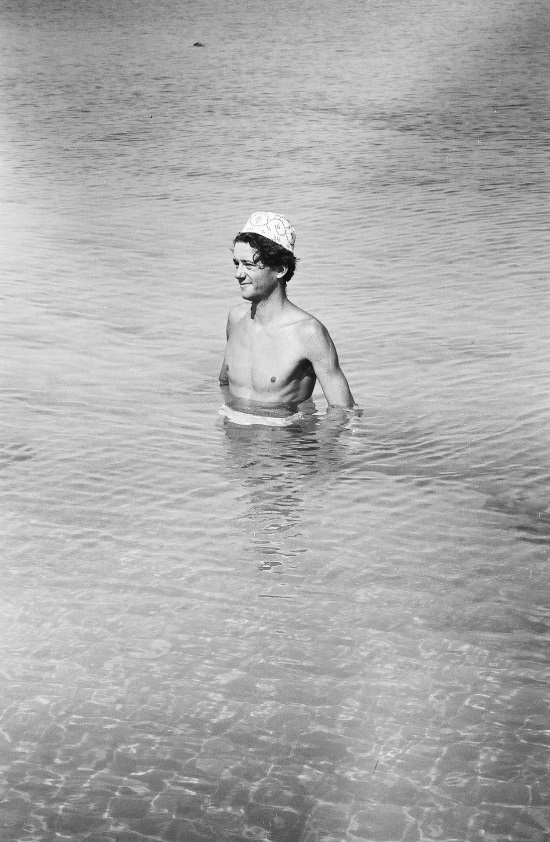

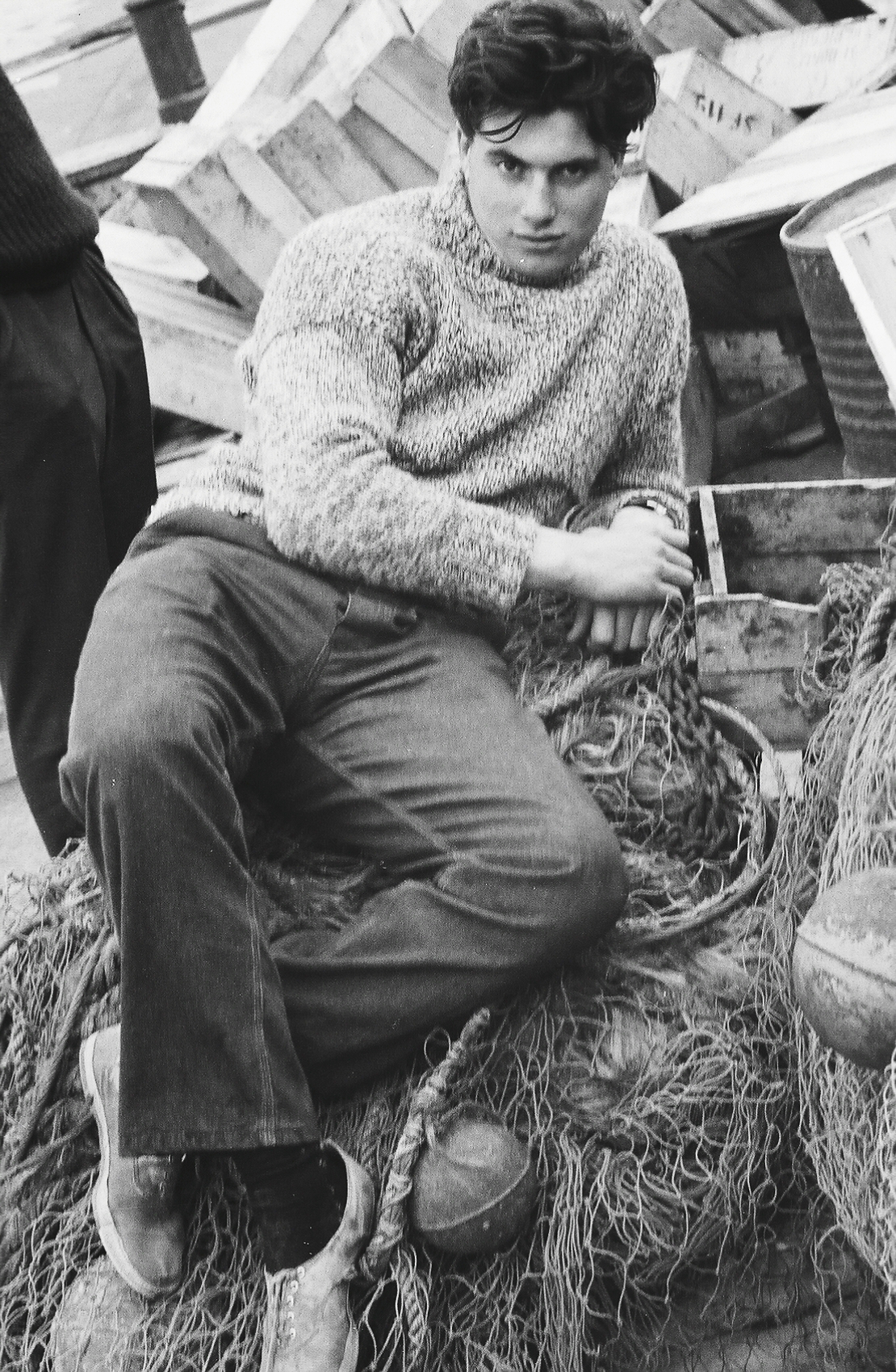

Graham returned in 1962 with his wife, as recounted above, and was joined by Chris Kendall and Paddy Skipwith immediately following their trip to Kharg Island. Some nice photographs of Graham and the entourage survive from that time. I've resisted the temptation to crop them, and they will all enlarge massively when clicked on.

David John James Kinsman

Princeton UniversityThe Department of Geosciences

15 Sep 2021

The Department has received word that former faculty member David Kinsman passed away in Kendal, UK on 8 Sep 2021 following a brief illness. David came to Princeton as a Postdoctoral Research Associate in 1964 and joined the faculty the following year. At Princeton, his research focused on carbonate sediments and evaporites, and he led a large student-centered project studying the geochemistry of the New Jersey Pine Barrens. He left Princeton in 1976 to become Assistant Director of the Freshwater Biological Association in Windermere, UK. Upon retirement, he devoted his energies to raising and writing about Hebridean Sheep (Black Sheep of Windermere: A History of the St Kilda or Hebridean Sheep, 2001, Windy Hall Publications), conserving birds, and developing an award-winning garden at his home in Windermere in the British Lake District.

Kendall "David Kinsman and his wife Rowena arrived in Abu Dhabi after the celebrations of New Year’s Day (1 Jan 1963). When Paddy and I met with Dave and his wife, we offered our friendly greetings and were surprised when they behaved antagonistically towards us. It involved very strange and direct insults in our faces, and rejection of our welcome. We had no idea what David and his wife’s problem was with us, but rather than take it passively, we responded in kind. We never became his friends and never had any professional dialogue with him. I think Kinsman’s relationship with the Evanses matched Paddies and mine. Graham never said any kind words about David in my presence. Later at IC David avoided talking to Paddy and I. He never modified his position. In letters Godfrey Butler wrote, he complained David had never confided with him the research they were both doing on evaporites. Doug Shearman who was mentoring Kinsman, Godrey Butler, Patrick Skipwith and myself but seemed appeared mesmerized by what he considered was Kinsman’s genius. Doug never seemed to appreciate that Paddy, Godfrey and I might have any scientific ability or future careers at the cutting edge of geological science. David’s animus to me was later true when I met him in the USA at professional meetings. I can only suppose he childishly resented Paddy, Godfrey, and I for being on what he considered his exclusive turf in the Trucial States. Doug Shearman meanwhile admired David. David’s publication record was certainly cutting edge while he was at Princeton and focused on evaporites and carbonate geochemistry. Later he changed his career and interests when after leaving Princeton he was employed by the Freshwater Biological Association in the Lake District of Britain. From 1979 through 1987 he conducted research and published on the soils and waters in the Lake District, particularly around Lake Windermere. Now in 2021 he is living at Windy Hall, Windermere caring for an exotic flower garden, waterfowl and mountain sheep."

Christopher George St Clement Kendall

Department of Geology, Imperial College, London

Sir Patrick Alexander d'Estoteville Skipwith

Department of Geology, Imperial College, London

Bon vivant, busker, scholar, wicked uncle, great and dedicated field companion, father of Zara, Alexander, Grey, Louis and Nikolai and eccentric husband to his wives from the 1st (m 1964 div 1970) Gillian Harwood, 2nd (m 1972 div 1997) Askhain Bedros Attikian, 3rd (m 1997 div 2011) Martine Sophie de Wilde, and the 4th (m 2012) Katherine Jane Mahon. Educated at Harrow, Trinity College Dublin with 2nd Honors degree and a Master of Arts (M.A.), and Imperial College London with a DIC and PhD.

Career started as a marine geologist in Tasmania; then Malaysia 1967–69; West Africa 1969–70; Directorate General Mineral Resources Jeddah Saudi Arabia 1970–71 and 1972–73; geological editor of the Bureau de Recherches Géologiques et Minières Jeddah 1973–86, Die Immel Publishing Ltd, 1987-1996 (Man Dir 1988-89), and Dir Geo Edit, London 1987-1996; Head of Translation, BRGM. Orléans

Godfrey Butler

Despite my recollections of Godfrey as the quintessential Englishman abroad – cool, precise and impeccably attired – I suppose there must have been occasions when he was as hot, bothered and battered-looking as the rest of us. The photograph below was not taken on one of those occasions!

There are a good many references to him in my diary, but I don't think his fieldwork overlapped Chris' to any great extent. He was at that time in his first year of an MSc course with Graham Evans as supervisor, followed in due course by a doctorate.

In addition to a most successful subsequent career in petroleum geology, he has also become the father-in-law of the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights, Prince Zeid bin Ra'ad Zeid al-Hussein of Jordan.