Memoirs of an Anglo-Irish Rock Hound

by

Christopher George St.Clement Kendall

There was a young man from Stamboul

Who soliloquized thus to his tool:

'You took all my wealth

And you ruined my health,

And now you won't pee, you old fool.'

Kurt Vonnegut Slaughter House Five (1969)

Chapter Six – Stranded on a beach

among the Bedouin

of Abu Dhabi

DEDICATED TO MY GOOD FRIEND

SIR PATRICK ALEXANDER D'ESTOTEVILLE SKIPWITH,

12TH BARONET.

Bon vivant, busker, scholar, wicked uncle, great and dedicated field companion, father of Zara, Alexander, Grey, Louis and Nikolai and eccentric husband to his wives from the 1st (m 1964 div 1970) Gillian Harwood, 2nd (m 1972 div 1997) Askhain Bedros Attikian, 3rd (m 1997 div 2011) Martine Sophie de Wilde, and the 4th (m 2012) Katherine Jane Mahon.

Educated at Harrow, Trinity College Dublin with 2nd Honors degree and a Master of Arts (M.A.), and Imperial College London with a DIC and PhD.

Career started as a marine geologist in Tasmania; then Malaysia 1967–69; West Africa 1969–70; Directorate General Mineral Resources Jeddah Saudi Arabia 1970–71 and 1972–73; geological editor of the Bureau de Recherches Géologiques et Minières Jeddah 1973–86, Die Immel Publishing Ltd, 1987-1996 (Man Dir 1988-89), and Dir Geo Edit, London 1987-1996; Head of Translation, BRGM. Orléans.

Patrick was the son of Grey d'Estoteville Townsend Skipwith and Sofka Dolgorouky (descended from Rurik, Prince of Novgorod considered the founder of Moscow, and a Greek slave-girl won by a Polish count from an Austrian prince in a card game. On her mother's side she was descended from Catherine the Great's illegitimate son, Count Bobrinsky, and from a foundling probably the child of the Tsar's brother).

Preface

This narrative is sourced from letters written to Sue King, of Harrow on the Hill, the memory and notes of Robin Waddell, my memories of adventures in the field and photographic record I made of the events that engulfed us. It describes why a field season that covered three months' duration only involved some three weeks devoted to field work as we coped with difficulties associated with equipment failure, health, weather and a classic case of misinterpreted social behavior.

It provides the collective story of the author and his compatriot students and academic advisors associated with the third Imperial College geological expedition of early 1964 to Abu Dhabi. We were studying the coastal sediments of the British Protectorate Trucial States. Graham Evans of Imperial College had earlier launched the first foray to study the coast of Abu Dhabi in 1961. This and the series of expeditions that followed were at the invitation of Iraq Petroleum. Geologists of this company and from academia, had recognized this area in the Gulf as the site of the accumulation of modern carbonate sediments. These sediments were thought to be similar to those associated with the newly discovered and explored oil fields of the Middle East, particularly Abu Dhabi. Graham worked with Douglas Shearman and Professor Dan Gill, the professor of Petroleum Geology at Imperial, and assembled students to study the area.

Our group consisted of my buddy Sir Patrick Alexander D'Estoteville Skipwith, 12th Bt., Paddy or Pads depending on our mood, friend and companion from the Geology Department of Trinity College Dublin and partner on our earlier joint expedition to the Persian Island of Kharg; Robin 'Scrapper' Waddell my trusty hardworking mild-mannered field assistant from whose clutches we kept the handy bottle of whiskey well away so he did not transform Hyde-like into an aggressive but still lovable pugilist; Godfrey Butler evaporite geochemist who cleverly transposed the numerical code on the tin cans of our food supplies when the tins lost their paper labels in the floods described below and my roommate in London who later found me employment with Exxon; Nick Page a field assistant seconded to our expedition by his father, the local manager of ADMA (Abu Dhabi Marine Area) and friend of my mother, later to go on to Oxford for a medical degree and fondly commemorated here for generously sharing his girl friends in London; Douglas Shearman a paranoid chain-smoking eccentric imaginative expert carbonate petrographer with a personality molded by serving in WWII in Atlantic conveys as a radio operator, charged to be our passive and aggressive supervisor preoccupied with a middle class suburban respectability despite having lived at the edge of civilization in Palestine when Israel was created; Graham Evans a sociable, jolly and experienced sedimentologist and field geologist who organized and coordinated the expedition and introduced Paddy and me to Abu Dhabi with his gorgeous wife Rosemary on our first trip to Abu Dhabi in 1962 when we camped on a Saadiyat Island devoid of population; Professor Daniel Gill, who in his early career had been Burma Oil's exploration geologist in Assam then department head of Geology at Trinity College Dublin and now Professor of Petroleum Geology at Imperial College, the penultimate figurehead and worldly-wise guru of the expedition whose kind edicts from London rescued Paddy and me from the consequences of our misrepresented actions in Abu Dhabi, and saved our careers at Imperial College.

National Geographic Map of the Trucial States in 1971,

with outrageous transliteration of Arabic names.

The Qasr al-Hosn, the palace of Sheikh Shakhbut bin Sultan Al Nahyan,

ruler of Abu Dhabi from 1928 to 1966

26th – 28th December 1963

The narrative of this unfolding tale begins on the day after Christmas 1963 when the flight on which Paddy, Robin and I had planned to go to Bahrain was delayed and we overnighted in London at hotel to have that final embrace with our respective girlfriends. Next day, on the 27th, we flew off for Bahrain for what we believed to be an uneventful plane trip from London, though later others were to think otherwise. We flew over Greece in the afternoon, disappointed not to have aerial views of the Parthenon. Non sequitur as it seems, Ancient Greek society and the infamous or famous Alcibiades, a contemporary of this temple, featured later in the discussions we were to have beside camp fires under the starlit sky when we were camped out on the Abu Dhabi salt flats. With times on our hands, and stirred by our remote setting we were to have the feeling we were the inheritors of a life style and the ideas of a long line of precursors from Ancient Greece with whom we felt a great affinity.

On the plane to Bahrain we were surrounded by a sea of drunken oil drillers and roughnecks who were already celebrating the coming New Year. We overnighted in Bahrain and unable to afford the hotel we spent the night at the airport talking to the taxi drivers, attempting to learn Arabic, and napping draped on the uncomfortable airport furniture. On the morning of the 29th we went into Bahrain to visit and converse with the geologists at the Shell Oil Company. Unbeknownst to us our allegedly outrageous behavior on the plane and our socialising with the Bahraini taxi drivers offended the Dutch hierarchy of Shell and they telegraphed Professor Gill, our protector, that we had let down Imperial College by being drunk on the plane (untrue) and scandalously spending the night conversing with the natives who should have been off our social scale. I guess Prof and maybe Graham calmed the situation when they heard these stories. They had both lived in the wilds and had relied on local nationals to help in the field and would have understood our bracketing with the drunken population of the plane and trying to improve our almost nonexistent Arabic with free instruction from the locals!

28th December – 14th January 1964

After changing planes in Bahrain we arrived in Abu Dhabi 2 days after leaving London. Abu Dhabi was unchanged from the previous year. Dusty, sandy, littered with rusty tin cans, undeveloped and glorious. All the small palm leaf houses we remembered remained; Bedu abounded, slouching through the dusty alleys draped with rifles and bandoliers, curved knives in their belts, bearded with shoulder length hair covered by colorful shawls. The desert and the sea still dominated the town with its patina of dust, which despite its lack of glitter remained the magnet that attracted these gentlemen of nature, thin but with character carved in their faces, on their camels, or oftener Landrover, and/or in beautiful dhows, bellams and booms. The sea was a breathtaking blue and the sky clear and a lighter blue. No boats appeared to be moving when we first saw this scene, since there was a Shamal blowing, a strong onshore wind from the Northwest, though normally one could see white curved sails winging across the blue. We were glad to be back but missed the girls we had left behind in London.

I wrote letters home stuck cross legged in the corner of our palm leaf house (Barusity). These Abu Dhabi native homes, rather like a south sea island long house, were airy and comfortable. Not far away we could hear the sea pounding on the shore. Paddy and I were awaiting Tarish, our Bedu taxi driver while I wrote my letters.

Remembering the Trucial States and the characters of Abu Dhabi, their society suggested to us that we were participating in something rather similar to a Russian novel or play. Chock-full of multiple characters with complex names, a plot, money, and politics, all stirred into a mélange of both overt and covert activity. Viewed from the distance and in the photographs that accompany this narrative, one first sees what appears to be a Rio de Janeiro like favela but, unlike the favela with a society dominated by criminal gangs, Abu Dhabi was populated by an impoverished, sophisticated, organized, predominantly Bedouin Arab society, though often parochial, and hierarchical, based on well-polished traditional ancient Moslem ethics and religious rules, geared to nomadic survival at the edge of the desert. Living symbiotically as bottom and filter feeders were the Baluchi, Indians, English and a few scattered European stragglers.

Influenced by a perspective of the world colored by our naiveté as recent undergraduates coming from an almost totally different society, we still recognized in our letters home that these people would eventually become important to both Abu Dhabi and the West. Here in Abu Dhabi the oil fields were potentially larger than those of Kuwait and we recognized that that the town and state might soon evolve into an important microcosm to become part of the ever evolving wider world occupied by Britain and others from which we had stepped through the portal of air travel into Abu Dhabi.

After our arrival we indulged in a grand sponging spree. We paid our respects to all and sundry of the inhabitants of Abu Dhabi. We took care to say hello to all of them, for each little group could be likely to play an important part in our lives. Roughly Abu Dhabi social hierarchy could be divided into the British Government representatives (the Political Agent, Colonel Hugh Boustead, equivalent to British ambassador to Abu Dhabi 1961 to 1965, and Bill Clark the Ruler's Advisor); the managing personnel of the oil (Page of ADMA and Chris and Gilly Willey of ADCO (Abu Dhabi Company Onshore)); the contractors developing and supplying Abu Dhabi (Gray Mackenzie's, the distributor of booze); our local grocer the Indian, Bullchand, who with his low-profile woven palm leaf dusty store was later to become a multi-millionaire; and the local Arab ruling clique. All the people of these disparate groups stood out as individual characters, particularly the Arabs and British Government.

The Arab society that affected us was:

Sheikh Shakhbut bin Sultan Al Nahyan ruler of Abu Dhabi from 1928 to 1966

Sheikh Zaid, Shakhbut's brother, later ruler of Abu Dhabi from 1966 to 2004 and president of the United Arab Emirates for 33 years from 1971 to 2004.

Sheikh Said, Shakhbut's eldest son

Sheikh Sultan, Shakhbut's youngest son

Shakhbut's wife, Sheikha Mariam bint Rashid Al Otaiba

Sheikh Said Tariq bin Taimur, brother of the Sultan of Oman and Muscat, Sheikh Said Tariq bin Taimur. The latter was known to have said "Keep the dogs hungry, they will follow you". As the last feudal monarch of Arabia this was his ruling philosophy and his subjects, the so-called dogs, were indeed hungry, but had no choice but obediently followed their master.

Shakhbut was then a thin ancient gentleman with a dyed black beard. He looked as if the wind would blow him away. Still he kept the reins of power firmly in his grip. No-one really knew his mind or whether he was a miserly old fellow or a shrewd business man. After the discovery of oil in 1958 he kept his oil royalties in Rupee notes in flimsy jerry cans beneath his bed, but by 1964 there were so many cans that he started putting this money into the Midland Bank.

On principle he opposed all European ideas and would always question a contract. When we were in Abu Dhabi in 1964 he had not decided on the size of royalties he would accept from ADPC (Abu Dhabi Petroleum Company). Cannily he appeared to be waiting for the oil field to be fully developed before acting. Wise old man that he was he tried to induce the Oil Company to develop an infrastructure while not acting on it himself.

In 1964 an electronic breakthrough came when Abu Dhabi took the step of acquiring a telephone system; though there was no hospital. "My people have been kept healthy by God for so long now, so why do we need a hospital now?" was Shakhbut's explanation. A further example of his applying brakes to development was the road from Abu Dhabi to the oasis district of Buraimi. In 1964 this was nothing but a dirt track fingering out across the great salt marsh or sabkha around the south Abu Dhabi Island and then across the hundreds of miles of rolling dunes of the Rub Al Khali. It was proposed that there should be a good highway all the way to Buraimi. However this road never left Abu Dhabi Island, for Shakhbut had made a financial decision and construction stopped.

Most of Shakhbut's predecessors died violent deaths. However despite his unusual frugal ways he brought stability. He pretended never to recognize anyone and so appeared to be extremely rude, yet when he wanted to he was charming and all crumbled before him. Very medieval in attitude he enjoyed hawking and had 50 of these birds. He was self-restrained and had only one wife.

In 1963, the previous year, Paddy and I had an audience with Sheikh Shakhbut in his fort-like palace in Abu Dhabi accompanied by Bill Clark. Bill was his advisor and had been installed by the British Government. Bill sat to the left side of Shakhbut, the side where he commonly hawked and spat across and over Bill. Bill translated for Paddy and me. We presented ourselves as free-spirited Anglo-Irish lads with deep affinities to the Bedu of Abu Dhabi. We explained we were exploring the beauties of the land while pushing back the barriers of science. We were not sure how much Bill had translated but I am sure Pads and I made a memorable impression on him but maybe not Sheikh Shakhbut. Bill Clark befriended us and lent us best-selling books from his ever expanding library shipped each month from Britain.

When we were in Abu Dhabi in 1962 through 1964 Sheikh Zaid lived in Buraimi, the oasis district close to the Muscat border. It is still a green and lush area which flows with water and when compared to the empty desert devoid of vegetation, is a paradise. Zaid was held in very high esteem by his people, a striking man who unlike Shakhbut wished to develop Abu Dhabi quickly. Though he was also a great hawker, he differed from Shakhbut in that he changed his wives once a year; acquiring his new ones from the local Bedouin tribes. In fact wives then were rather like second hand cars. It was rumored that when Arabs had had enough of their wives they could point at their wife and proclaim loudly I divorce you, I divorce you, I divorce you. That was that and the newly divorced could look around for an upgrade. A short time after we were in Abu Dhabi in 1966 Zaid became Shakhbut's replacement, a ruler elected by a majlis, a meeting or special gathering representing the ruling family. Shakhbut was exiled for five years, then returned to Abu Dhabi, living on until 1989.

On the UK side of society, of particularly important to us were Chris and Gilly Willey who very kindly installed us adjacent to their house in a barusity, a hut with basket-work reed walls situated in their compound. It was then, probably on January 1st, the day after our arrival, Robin Waddell had lost control at both ends (as a result of dysentery contracted at Bahrein airport). Later he often wondered which of us cleaned it up afterwards.

The day after Robin's collapse we drove him to the ADPC Medical Centre, a dark little shed where a dark little Indian injected Robin in his 'jolly old stomach wall' using a curved needle that looked about 9 inches long and which he claims was 'seriously painful'. Robin said that the Indian medic certainly knew his stuff since this event was the turning point in the diminishing of his stomach problems. The Willeys then even more kindly put Robin up in one of their spare rooms while he underwent a 12 day fast, nil by mouth except boiled water.

In our time in the Middle East and Abu Dhabi, chance connections proved really important to us all. For instance it was incredibly fortunate that when Robin had been initially introduced, Chris Willey had recognized Robin's surname and it turned out he and Gilly were great friends of Robin's father's pukka cousin John Waddell and his wife Julia, who lived in Trebovir Road, just off the Earls Court Road; so there was also an element of personal connection in their kindness. And a couple of months later, following Robin's fisticuffs in a drunken fracas with an unreasonably officious British Army sergeant whom he challenged to a fight at the Trucial Oman Scout Fishing Club in Sharjah, Chris Willey arranged flights to Bahrain and back, and accommodation in the company quarters, for surgical treatment to Robin's broken nose so even if it was no longer so handsome as before, after surgery it was able to function just as well if not better. Viva the old boy club and Empire, pink gins all round, and who's for another chukka?

Astonishingly, later the following year, quite coincidentally, Robin and his new squeeze Sonia Kaulback bumped into the Willeys in the aisle of a West End theatre. By that time Robin wondered if Chris had decided that he had had quite enough of Robin Waddell for one lifetime, as so many people do, but he greeted Robin as a long lost friend, sort of. Certainly unexpected people took care of us and saved our skins several times over.

By the 6th January we still had not left Abu Dhabi. At that time for three days it had done nothing but rain continuously. The weather of Abu Dhabi was not at all like that of a desert but more like a tropical rain forest though there were no trees, or perhaps the West of Ireland with no grass? Fortunately we were able to put canvas from our tents on the roof of the palm leaf house and so only became damp instead of being soaked. That day a strong onshore Shamal was blowing again and we mistakenly believed the weather might be clear the next day. All the roads across the salt flat lining the coast were impassable and the airfield was out of action. Abu Dhabi was cut off from the world, except by sea. Not quite the welcome we expected of Abu Dhabi.

The rain drove in two dogs to share our existence. One slept on the end of my bed on my feet. Not exactly comfortable for either of us. I kicked out several times but being a persistent dog and obviously long suffering, it just wriggled onto my feet, groaned and went back to sleep. The dogs were a sort of a saluki-greyhound type. No very aristocratic but actually quite intelligent. Both were bitches.

We were now waiting for the weather and my echo-sounder before setting off in the boat. Robin and I planned to go west to a lagoon known as the Khor Al Bazam. Khor is Arabic for channel and is pronounced 'whore'; so in later in polite society, hem hem, it caused a few raised querying eyebrows, don't you know, when I referred to the area I was working in as though it was the local brothel.

Perhaps it is now in order to provide a geography lesson on Abu Dhabi so the reader knows where the Trucial States are and where we planned to go. Abu Dhabi was one of the Trucial States, later to become Emirates, which were and still are under the control of seven emirs, namely Abu Dhabi, Ajman, Fujairah, Sharjah, Dubai, Ras al-Khaimah and Umm al-Qaiwain. All of these states, except Abu Dhabi, were and are very small. In contrast Abu Dhabi has a long undefined border with Saudi Arabia across the Rub Al Khali or the Empty Quarter. This is a vast sand dune area and some dunes are over 300ft high. The edge of the Rub Al Khali is marked by the oases of the Liwa to the East and Buraimi to the West on the Oman border. On either flank Abu Dhabi is bounded by other countries. To the west is Qatar which in 1964 was a rather poor but oil producing country; to the east is Dubai, a State of Trucial Oman whose prosperity mostly depended on gold smuggling, gun running, slaving and other illegal activities. Most of Dubai's wealth came from Pakistani and Indian gold smuggling but this often ground to a halt with changes in the value of gold in these countries. Britain administered the external affairs of all the Trucial States till 1971 when they changed their status and became the United Arab Emirates independent of Britain. While the Trucial States existed, Britain maintained Trucial States armies, fought their wars, and represented them diplomatically abroad. However internal affairs of the Trucial States were their own. It was a very loose but amicable agreement which the Trucial States kept in place since it gave them protection from the Muscatis and Saudi Arabians, all of whom coveted the area of Abu Dhabi for oil wealth. In 1964 Abu Dhabi was the only one of the Trucial States in which oil had been found and this was in quantities which that at the time was thought to probably surpass those of Kuwait.

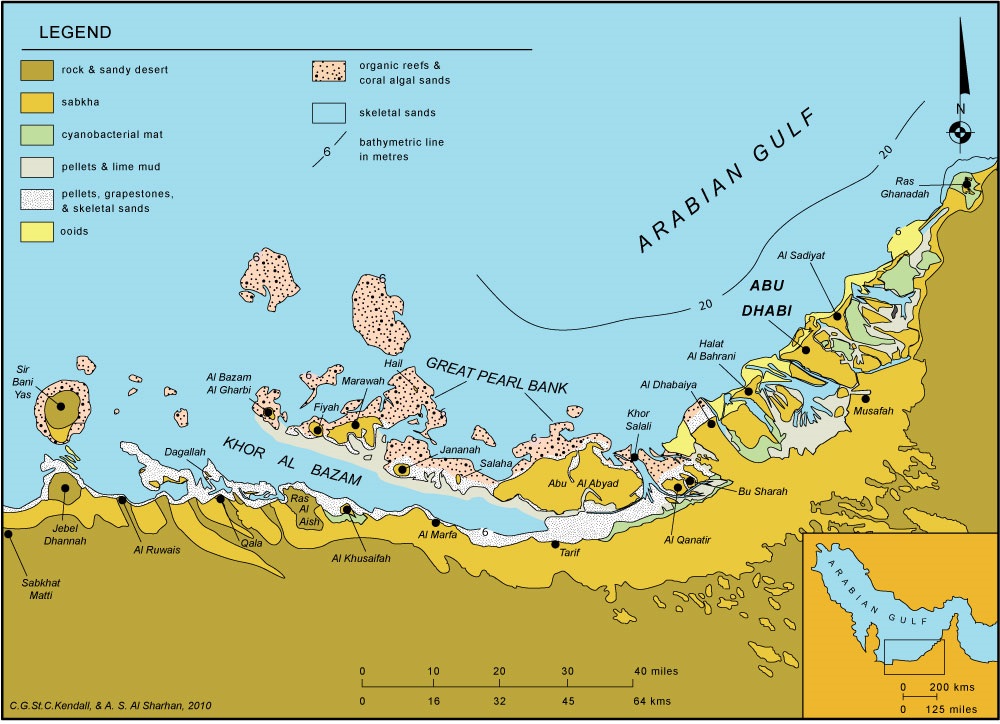

The Trucial Coast States, now the United Arab Emirates (UAE), is located on the eastern side of the Arabian Peninsula, between latitudes 22° 40` and 26° 00`, and longitudes 5° 00` and 56° 00`. It parallels the approximately 600 km long linear southeast coast of the Arabian Gulf between Qatar and the northern end of the Musandam Peninsula (Oman). Here relatively pure carbonate sediments with minor quartzose components accumulate. These sediments vary laterally in character. To the west the Qatar Peninsula provides protection from heavy seas, while the central coast is protected by the 60 m deep broad shallow shelf of the Great Pearl Banks; and the northeast part is unprotected, facing directly towards the northern Shamal winds that come along the entire length of the Arabian Gulf as can be seen in the regional photo of the complete Gulf and the UAE coast. The complex of islands and tidal channels mix the effects of tides, wave, water chemistry, temperatures with the associated carbonate and sabkhas or arid salt marsh settings.

Seaward reefs, barrier islands and tidal flats characterize the today's shallow-water carbonate and the tracts of sabkha or salt flat coast subject to frequently flooding by the sea driven on land by Shamals. These sabkhas line the coastal embayment of Abu Dhabi along the southern Gulf coast. The offshore bank extends seaward to the north into the Gulf through coral reef growth and tidal delta formation. South of these banks, sabkha salt flats are encroaching on the lagoons with a combination of beach ridges and algal flats. The sediments of this coastal region mark the transition between landward continental sediments and seaward carbonate sediments. To the east, the modern coast of Abu Dhabi trends northeast-southwest and is composed of a barrier/lagoon complex which narrows northward. To the west, in central Abu Dhabi, the protecting barrier islands are more widely spaced than those to the east and are marked by extensive carbonate shoals and coral banks cut by tidal channels. South of the barrier is a continuous open body of water the Khor Al Bazam lagoon with its western end connected to the Gulf. The intertidal coast is lined by widespread intertidal algal mat that lie seaward of sabkha salt flats.

So much for the borders etc. Abu Dhabi is mainly desert and is extremely poor agriculturally. In the early sixties Liwa and Buraimi were the only places where anything grew before the recent advent of reverse osmosis and the lining of all the now paved road with trees and shrubs. Its shore is bounded by numerous islands. Inland the sabkha stretches for some five to ten miles in width as a ribbon parallel to the coast. This salt flat bounded the coasts of most of the Trucial States. To the south comes a narrow belt of low hills, some 50 to 100 feet high and further to the south comes an empty sand dune terrain.

Robin and I were now planning to go to an area of sandy islands and blue sea south of the Great Pearl Bank, creeping with fish, turtles, sea snakes and manatees, the herbivorous seal now believed to be the origin of the mermaid or sea siren myth. Fortunately the oil camp of Tarif, and Trucial Scout army camp of Mirfa, were handy for civilized meals and the logistics needed for our field work. Most of the time Robin and I planned to, and did eventually, camp from island to island. A really terrific existence. Just what we needed. Most of our equipment was now repaired (9th January) and we were trying it out the next day. Weather permitting, we could go! But then again it looked like rain and wind so again we postponed to the day after. This was repeated ad nauseam, day after day.

The weather and/or equipment troubles had held us up ever since we had arrived and then at last all seemed set for escape. Colonel Hugh Boustead the British Political Agent invited us all to stay and we wined and dined very well, had loads of hot baths and slept in dry beds. The only thing exciting to happen to us then was that Paddy found a baby Tarantula spider in his bananas. It leapt at him, he leapt away and we all laughed. It was only ¼ inch long. This meant of course in the events that followed that a Roman omen was being signaled to us! Once again we were delayed by weather.

We had plenty of time to make sure our field equipment was ready for use including the 17ft Imperial College launch, its echo sounder which we used to determine the depth of water in the lagoons we were to navigate and sample, our handy dandy Optimus double burner petrol camping stove with its constant need for leather valve washers, camping lantern mantles leather valve washers and our food and beer. We had stocked up on canned food in London and shipped this to Abu Dhabi. We supplemented this with rice, curry powder and chutney hunted from the dusty shelves of Bulchand's well stocked but gloomy grocery. His had been the only grocery in town for some time and all and sundry including even Sheikh Shakhbut brought from this dank cave in the heart to the Abu Dhabi souk. We stocked up on canned beer from Gray Mackenzie's.

On the topic of food Paddy and I conceived the idea of purchasing dates shipped in palm leaf paniers from Iraq to Abu Dhabi by dhow. We hoped to eat dates and so mimic the Bedu by supplementing our diet of canned goods. We went ahead and brought a pannier oozing date sugar and divided its contents placing this in some of the multiple plastic bags we had previously planned to store our sediment samples. These bags we filled with two or three handfuls of dates in each. Congratulating ourselves on saving a fortune for food we set to and tasted a few of the dates. It seemed as if they had only to touch our lips and we fell violently ill with dysentery. Being of delusional very British mindsets as soon as we recovered, we believed we had built up an immunity to whatever was causing the dysentery, and we tried on several occasions to switch our diet to dates. The lip test showed there were limits and we gave up on the mad dogs and English approach and tried to give the dates to passing Bedu who asked for fruit when we were in the desert. The Bedu, impoverished as they were, angrily refused our gifts and persistently asked for canned fruit. It would appear once you have eaten an infected Iraqi date you are cured of them for a lifetime.

Looking back I remembered when at the age of eight travelling on a ship with my mother and father from Glasgow to Basra on 11 Apr 1946. When we arrived in Iraq and anchored on the Shatt al Arab in the delta formed by the Tigris and Euphrates rivers surrounded by groves of date palms that lined the delta channel, a boat man offered me a date. I promptly ate this and in a matter of hours became deathly ill with dysentery, waiving in and out of consciousness. Next morning my take charge mother hired a small motor launch and took my father, who was overcome by the exhaust fumes, and myself to Basra and the local hospital. The medical staff fed me the latest medical fad, sulfur drugs, and I miraculously recovered sufficiently to remember my arrival by train from Basra to Baghdad and being met by my colonial uncle Conrad de Courcy and continuing my life at the edge. From then on till my Abu Dhabi adventures with Iraqi dates I had a well ingrained phobia against them much of the chagrin of my Arab friends who could not understand this aversion.

The weather had been so bad, we decided we should tow the boat by land on a trailer to where Robin and I wanted to work, which was some 40 miles away to the west at Tarif. However, once again this proved another disaster and my ill-advised decision. The trailer with boat on it quickly became stuck in the soft sand just a few yards from the shore. By next day we had only travelled ½ a mile, while meanwhile we had lost a tire and broken a winch on the lorry. It now dawned on us that we would never make Tarif by land, so I had a change in plan and now had the boat towed into Abu Dhabi and put in the water by crane. For sure this was much more sensible for if we had continued to try to take the boat by land it would have been stuck in the sabkha flat salt marsh which was flooded by the heavy rains. Paddy had just spent an agonizing 25 hours in a Landrover and had only just travelled that 40 miles along flooded roads and this helped us decide again on a sea passage.

Since the boat was in the sea, all was set to go to Tarif by sea and to hell with the weather! Then we had another setback when the driver of the lorry which had towed us out of the sea and was originally to have driven us to Tarif demanded full payment for work he hadn't performed. This was despite the fact we hadn't gone 100th of the distance but back to the Abu Dhabi jetty. This driver wore a distinct blue shirt known as a thobe or dishdasha to his ankles. He came from Dhofar (Hadraumat). He wanted the equivalent of £35 for something he hadn't done. We took him immediately to court, at least I did, and that same morning we two, blue dishdasha and I, plus an interpreter, were perched on chairs in front of a religious sheik, judge or qadi. Blue shirt demanded 400 rupees, and I offered 100 rupees. The qadi was a frail man, in a white headdress with a cord circlet to hold it down. He was in a white dishdasha and a cast-off double-breasted Burton's jacket. He was a quiet but rather quick witted gent. He said that I had never changed the contract with blue dishdasha, so I pointed out that when we initially became stuck I said I didn't want to go to Tarif anymore. True I hadn't discussed prices but this was a new contract. The old boy said that in my heart I may have changed the contract but I hadn't said so. Our blue dishdasha friend managed to get 270 rupees or nearly £20 but the qadi saved us some money.

Meanwhile Paddy travelling by land set off for a place known as Jebel Dhanna where he was to collect another Landrover which ADPC was lending us for £1 per month. He hadn't gone two miles from Jebel Dhanna when, at 60mph along one of the sandy tracks they call roads, a tire burst. The suspension was smashed but all the occupants of the Landrover, namely Paddy and his driver Aber, a Bedu from the Liwa, were OK. Paddy then tried to set off in another Landrover but this one's fan belt broke. Paddy then returned to our camp at Tarif just before I left with Robin for the field on the 17th of January.

14th – 16th January 1964

When Doug Shearman and Godfrey Butler had arrived in Abu Dhabi around the 14th or so of January, Doug Shearman lobbed the bombshell at us that we'd been accused, Patrick, Robin and me, by an ADPC employee of drunken rowdiness on the flight to Bahrain and the word of this had got back to Imperial College, and Doug suggested that the whole expedition might be cancelled. Meanwhile Doug agreed to let Robin and me go to Tarif by sea so I could work in my field area in the western Khor al Bazam.

Some days later in mid-February Graham Evans fortunately came out to Abu Dhabi to soothe things down and we were able to continue with our adventures and he returned to Imperial College and London.

17th – 24th January 1964

So not to worry, next day off we went by sea, Robin and I. That night and the next day went well and we reached the Imperial College base camp set up by Doug Shearman and Godfrey Butler at Tarif. Our boat was in time to meet Paddy safely back from Jebel Dhanna. Yippees all round!

Oh by the by, I didn't mention that I had seen a dead cat and a dead cockerel close to the road. Unusual in Abu Dhabi because the Arabs here don't kill callously. A bad omen? Yes, look what happened with the driver in the blue dishdasha. Soon I expect whenever I see anything unusual it will be one of these bloody signs or Roman Omens.

Doug Shearman and Godfrey Butler had travelled to Tarif on the 16thand set up camp. This was just before the storm we were all soon to experience on the 18th that flooded their camp and dispersed our canned food over the sabkha salt flats, stripping off the can identifying labels. Tragedy of Tragedies the beer we had secreted among the cans of food floated off and completely disappeared into the sea or over the sabkha flats.

Robin and I started preparing the boat at Tarif, swinging the compass to plot the magnetic deviation, etc., etc., and when Paddy arrived, Robin and I offered to take him with us by sea to Jebel Dhanna since it was only a few miles from where I hoped to work. We set off in glorious weather. Blue skies. Not a ripple on the sea. We chased a huge turtle (6ft across). It looked so beautiful, slipping silently through the depths, its great flippers thrusting it along. There was a barnacle on its head. We saw thousands of cormorants diving in a shoal of fish.

We called in on the army camp at Mirfa on the edge of my field mapping area and collected a Verey pistol and shells. We joked about them with the Trucial Scouts, and showed them where we were going in the western Khor al Bazam and set off again for Jebel Dhanna full of beer. Archie, the major in charge, kindly had invited us to visit whenever we feel like it so we'd probably be spending quite a few days round there in the future.

Paddy had left his cigarettes behind at Mirfa and became super-anxious as he moved into the effects of nicotine deprivation. He decided to take his mind off his craving by becoming our now very depressed and nicotine-deprived steersman. The previous year in 1963 a similar thing had happened when Paddy and I were in the boat travelling in the Khor al Bazam. This time when we were without Paddy's cigarettes we set up camp on the shore and we saw lights glimmering in the distance. We then set off across the sand to investigate the lights in the blind hope we could find cigarettes for Paddy. We found a remote camp whose living quarters were metal boxes on wheels. We knocked on the tin shack door. Inside we found a bunch of US oil company geophysicists mapping the subsurface looking for oil traps. Luckily they took pity on Paddy and provided him with his much needed fix. We never explained to the gents we visited from where we were or how we came to see them, and when we reached our boat and camp we laughed between us joking that they must have thought we came from Mars. Years later at a geological convention in the USA I met one of the men who had been there and he commented that he had often wondered about our miraculous appearance from nowhere with no visible transport.

Back to 1964 and our journey to Jebel Dhanna from Tarif, that evening Robin, Paddy and I bivouacked on the Khor al Bazam shore with a canvas stretched over our oars and drift wood. We made a huge fire from the piles of wood left over and lay out under the stars. As it was the beginning of Ramadan (the religious month of fasting representing the Mohammedans' equivalent to Lent) the Moon and Venus formed the Moslem emblem. The moon was very thin and on its back and seemed quite unlike England's, though it clearly of course must have been. The stars really glittered brightly on us in the Trucial States and it seemed as though the sky was very much closer than in the UK, the atmosphere being so much cleaner and clearer.

We motored off for Jebel Dhanna next day hoping to reach there by lunch. By ten o'clock the wind was blowing a howling gale and the waves were something to be seen. I was crouched down by the engine warm and cozy and protected from the wind, reading Wilfred Thesiger's book Arabian Sands describing his journeys by camel across the nearby Empty Quarter. Suddenly we couldn't see the land for the dust and we all became a little frightened as we lost sight of the landmarks we were using to navigate. Still we thought we knew where we were and we chugged on. The waves were becoming larger and we saw waves breaking over rocks and shoals we did not know. We became worried we might hit an unseen rock or become stranded on a shoal amid the breaking waves.

Paddy was steering and soon became soaked and very cold. Then, as we had worked our way into toward what we believed was the coast, we realized we were lost. We scuttled into shore to avoid the heavy surf but to where we now could see land plants sticking up through the sea surface. We anchored in the lea of a spit where the waves were pounding and later the wind howled all night. Just before we went to sleep and curled up on the bottom of the boat, very wet, we recognized that what was normally dry land was flooded too. An awful thought struck us, which was that the boat might now be floating over what had been dry land too. We consequently moved out to the North into 15 ft. of water and put out all our anchors at the end of long ropes and chains.

Robin later claimed (and still does) that it was my seamanship that saved us all three from perishing in the raging briny but I suspect rather it was a series of our collective decisions. I was however the warmest since I had been huddled down beside the warm engine cover beneath the shelter of the boats canvas splash cover. I was the most rational and recognized we were potentially in serious trouble and so we had made the correct decision to move into shallow water despite the wind howling around us and waves crashing over the spit!!

Next morning we found out that fortunately we weren't on land but now were stranded at the level of the high-tide. Even after two days the tide didn't come back. We were disappointed and couldn't believe that the tide had not come back in! I guess the seiche tidal influx was being balanced by a high tidal position further offshore.

The Shamal continued to blow a gale the following day and we huddled under our piece of canvas over the boat. Then much to our chagrin, just after breakfast, an R.A.F. plane circled us and despite signals from us indicating that we had all we needed, they insisted on parachuting food, water, and a rubber dinghy. The dinghy provided us with light relief when it automatically inflated on the tidal flats and then noisily deflated with whistling noises as the air escaped. The newspaper cutting my mother saved showed the pilot of the RAF plane had a different perspective of our situation.

I took a series of lovely color photos of the green parachute landing just by the boat. This was a drama which we viewed as quite unnecessary because we had ten days of food, including water and were quite obviously safe and unharmed. Doug Shearman knew this but I suppose he had been having kittens and told no-one He was an old hen. Do hens have kittens? Never mind but we were now expecting a land rescue party. We discovered later in a newspaper cutting my mother was to give me and I still have, that a British destroyer had got up steam in Bahrain and was considering coming south to the Khor Al Bazam and rescue us, Doug Shearman mobilizing our rescue, and no wonder that when we were found healthy and self-sufficient he treated us like badly-behaved schoolboys from the Fifth Form of Greyfriars School.

The RAF plane dropped a sick bag, you can see above, telling us that the Trucial Scouts were 3-4 miles away, which meant they would be bogged down in the salt marsh when we last saw the plane.

So far the storm seemed to have abated but the sun hadn't shone. We now knew where we were. We worked it out this to be Qala Bay, clearly visible on our aerial photographs. We were anxious to be off to sea and all we needed was the tide. Stranded on the upper portions of an intertidal algal mat we set up camp on the flats the day before the RAF dropped that rubber dingy which had promptly deflated. Then the next day a local Gulf Air flight came over our position and dropped a sick bag with a happy birthday message from my mother. From that birthday on Paddy always remembered my birthday and had contacted me every year since!

Later the day of the Gulf Flight we were approached from the land by three affable Texas Oil men, clean shaven with check shirts and broad brimmed cowboy hats. They had sensibly driven to our position on the tidal flat using the beach ridges that lined the coast for their path. On arrival, in the mistaken belief we had no alcohol, they had proffered us a bottle of whiskey to tide us over so we in turn shared cans of our warm beers with them. Paddy went off with them and Robin and I completed digging a ditch to the sea. We were able to use this to relaunch our boat when the tide came back.

The Trucial Oman Scouts rescue team turned up shortly before we could launch our vessel. As a result we were unable to escape their finger wagging and disdain for what they perceived as our boy-scout-like attitude and behavior. They were tired and dispirited and were not pleased with our happy faces and warm welcome. We had long ago worked out that the only way to travel in the sabkha was via the beach ridges and they were not pleased to hear that the Texas Oil men had no trouble in reaching us while they used direct line navigation across the soft wet salt-encrusted depressions that through their inexperience at driving on sabkha inevitably led to them being literally bogged down.

24th – 30th January 1964

Shortly after the visit of the Trucial Oman Scouts Robin and I took to the sea from our shipwreck site at Qala Bay and we made our way to Jebel Dhanna. Here we met Doug and left the boat at Jebel Dhanna. We travelled by Landrover to Tarif to stay with Doug and Godfrey Butler where they had been working together on the evaporites of the Sabkha flats for Godfrey's Master's degree.

In my letters home I could foresee lots of trouble over our shipwreck but reckoned it was not something to worry about! Wrong! No matter how hard one tries, "if God wills it" (Inshallah) unpredictably all may crumble though may later blossom and succeed.

30th January – 9th February 1964

Doug decided Robin and I could not go to sea till we had clearance from Imperial College and I guess this, coupled with the alleged drunkenness on the plane to Bahrain and also supposedly letting down Imperial College by spending the night at the airport talking to the taxi drivers, colored his opinion. It is my opinion that Prof Gill and maybe Graham calmed the situation but meanwhile Robin and I were taken by Paddy in his Landrover back to the shipwreck area of Qala Bay.

We planned to collect field samples both on land at Qala and later by sea when we could use the launch again. More of our misadventures with travel followed but our main objective for being in Abu Dhabi was to push back the barriers of science and use this to lead richer fuller lives in the pubs waiting for us at home. The stranding at Qala provided me with opportunity to study the sediments of the Bay. Using a long necked shovel Robin and I systematically collected the sediment placed in the plastic bags free of dates.

Robin and I collected sediments systematically from the intertidal and supratidal zone. Using aerial photographs and a sextant we were able to triangulate angles to prominent features in the local hills and so locate the samples positions. We sketched traverses from the sand flats from the low water up to the beaches and algal flats where we had been stranded. This way we were able to characterize the sediment and made a detailed map of the sediment types and their distribution. Later when I was back in London at Imperial College which was not a branch of Hogwarts School, I was able to make a breakthrough in the petrography of carbonate sediments when I established that blue green algae were infesting the tests of Peneropolid foraminifera and changing their mineralogy from high magnesium calcite to aragonite. Paddy and I published a paper on this phenomena.

We spent just over a week camped out amid the Tertiary hills. Our bivouac consisted of a couple of canvases spread over gullies cut into the sediment of the hill side and placed our possessions beneath them to protect them from the heavy dew. The humidity was so high that when the temperature dropped in the evening and through the night moisture collected on the local vegetation and on our sleeping bags. We tended to sleep outside to watch the stars and enjoy the cool air but every morning we would awake soaked by the dew. At night at Qala we usually cooked canned food flavored with curry powder and rice. The morning breakfasts featured porridge and strong Indian tea. We often made a fire from the drift wood that lay stranded in great lines along the shore. We had a small short wave radio which we used to listen to the BBC news and any local music we could capture ranging from Indian songs, warbling Iranian solo voices and Egyptian café orchestras with their multiplicity of different instruments.

While we worked at Qala Robin and I contracted some ailment and often felt very tired and staggered across the flats aimlessly at times trying to make good field observations and keep our minds on completing our studies. We enjoyed the desolation around us. We saw no one and achieved a lot despite our intervals off in la la land with our mysterious ailment. It was in this surreal out this world setting that Robin and I discussed Alcibiades and his buddies as we read my book of Ancient Greek history secreted in my luggage in preparation for the trip to Corfu I planned to make on the way back to London from Abu Dhabi.

9th – 15th February 1964

Pads arrived back to pick us up and take us to Abu Dhabi. His Landrover was loaded with five punctured tires and he was depressed and beside himself with how frequently his tires failed. As soon as we came to the track or road to Tarif another tire of Paddy's punctured. We dutifully got out of the Landrover and miraculously were fortunate to flag down a group of Bedu in another Landrover who lent us a tire. These Bedouin kindly and thoughtfully followed us. Then when we all could see the Al Maqta Fort guarding the causeway across the creek dividing Abu Dhabi Island from the sabkha, they overtook us for Abu Dhabi. As soon as they were out of sight we immediately had another puncture.

By now we knew the routine and Robin and I got out with Paddy. We piled the tires up and then out from the dusty haze came a Yemini with his head wrapped in a white shawl whose tip looped over his head and he kept in his mouth. He looked like a happy grinning Omar Sharif as he came bouncing down the Sabkha track in his huge late model American car lacking any but the most rudimentary suspension. He claimed to have come from the south, pointing at himself and saying "Janoobi, Janoobi", (the south, the south).

With practiced hands the Yemini efficiently placed our tires in his enormous boot and off we went to the Al Maqta Fort, abandoning Paddy hunched over the steering wheel of the Landrover which was propped up on its jack, to drown his sorrows alone with a bottle of whisky. This was the turning point for him and when we returned he was in tears and determined to return to the UK. We believe he concocted a story that his mother was ill, though she may have been, and shortly after he left for the UK.

Meanwhile Robin and I and the Yemini passed by the Al Maqta Fort. As if by magic, as soon as we no longer could see the Al Maqta Fort the Yemini's car with a loud bang then had a puncture and we swung bouncing off the road into the salt bushes. We were now some 12 miles from Abu Dhabi town but getting closer all the time.

Then, as if on cue, a group of Baluchi coolies came by in a huge truck of gravel and picked us up with all our tires; the Yemini's and ours. We perched among the deferential coolies on the gravel with our tires. Shortly after, the Baluchi coolies had to drive off somewhere else and abandoned Robin, me and the Yemeni on the Abu Dhabi road. There a short time passed and extraordinarily we were picked up by Colonel Boustead, who like Toad of Toad Hall, invited us to come to tea. The royal command "I say chaps come to tea" was inescapable and despite our remonstrations and expressions of worry for Paddy we cavalierly left him and the Yemini behind with our tires, Boustead claiming the Yemini would look after them. We had tea with Boustead and returned to pick up Paddy who was now in a whisky-sodden saddened state ready to desert the desert for home and family. What do you know, Boustead was right, and next day we found all our tires repaired in the souk. Bedu generosity and care came through once more.

Robin and I briefly worked with Paddy, Godfrey and Doug Shearman on the Abu Dhabi Sabkha evaporites digging trenches and building a sedimentological model of the Abu Dhabi sediments inland from the coast. Graham arrived in Abu Dhabi and granted Robin and me dispensation to work with the 17ft launch in the Khor al Bazam. Doug was the senior but he would defer to Graham.

15th – 25th February 1964

Now that Robin and I had permission to use the boat we were off to the wild blue yonder. This permission to conduct research work from the boat was provided so long as Robin and I maintained radio contact with the Trucial Oman Scouts on a daily basis. Collecting the launch we left from the harbor in Jebel Dhanna Robin and I motored off to begin our field work starting with the island of Bazim Al Garbi. We spent around a couple of weeks spending some night based close to Mirfa and some offshore from the islands including Bazim Al Garbi, Fiyah, Marawah, Janana and Salaha. Our field work involved cruising across the Khor al Bazam to these islands to the north on the Great Pearl Bank.

Again when Robin and I visited the islands we collected sediments systematically from the intertidal and supratidal zone. Our marine field work was somewhat similar to that of Qala Bay. We used aerial photographs and our sextant to locate the sample positions. We sketched traverses from the sand flats from the low water up to the beaches and algal flats of the islands creating maps of the sediment distribution. While at sea we used a grab sampler that was suspended from the davit on the stern of the launch, opened and dropped to the sea floor where it snapped shut grabbing soft sediment. We would anchor the boat and as before work out its position using the sextant and landmarks around us. We measured the Ph of the sediment.

Some nights Robin and I would overnight anchored beside the offshore islands, sleeping stretched uncomfortably on either side of the diesel engine. We used our Optima stove to cook, often fish we caught with a spinner we trailed behind the boat as we moved from station to station. Most nights were quiet and we listened to radio and ate our supper. However on one occasion Robin was pissed-off about something; I think I may have patronizingly insulted him by remarking on his puny Celtic body shape with his broad shoulders and long arms. He found the whisky, drank it down and Mr. Hyde materialized and challenged me to a fight. This caught me by surprise since we were miles offshore isolated by ourselves in our tiny 17ft boat. Not a perfect setting for fisticuffs. I assumed a voice projected in command mode and suggested this was a stupid suggestion and told him to stay at his end of the boat. It worked and Robin told me later he backed off when he realized he couldn't navigate our boat though he had been fueled up for an all-out assault. Funny about the navigation. I and Paddy I had picked this up from Graham Evans who showed us how to use a compass and sextant to locate sample positions. I know I was always surprised when went out of sight of land and then we turned up where we were supposed to. Science works.

When at Mirfa Robin and I had our bivouac close to a Bedu camp with its heavy black with white strip woolen tents and grazing camels taking advantage of the rain which had made the green salt-tolerant plants they ate flourish. The Bedu expected us to bring them fish when we finished field work. They were very disappointed when we came back with none. Robin and I were apologetic at letting down the community. We were supposedly an important supplier of food and they were fast friends who left our possessions alone when we were off in the field.

25th – 28th February 1964

Then inevitably the radio ceased to work so we decided to go to Mirfa to let the Trucial Oman Scouts know we were OK. We found no British NCOs or officers at Mirfa but there were Arab Levies who spoke no English. Robin and I were forced to set off to find the English officers closer to Abu Dhabi on the way to Sharjah. There Robin scrapped with the sergeant and let down the upper crust by not beating him to a pulp, though the regiment expressed great admiration with how Robin unsuccessfully defended himself.

28th February – 31st March 1964

Robin and I continued our fieldwork with the help of Nick Page. We confined ourselves by working on land along the coast of Khor al Bazam. We camped along shore though much of our work was done close to Tarif and Mirfa. We spent time making sampling traverses making a photographic record of the Cyanobacterial Mats growing over the tidal flats around Khusiafa.

Godfrey worked on examining and sampling sediments and waters and taking cores in the sabkha south east of the Al Maqta Fort.

1st – 26th April 1964

Robin and I returned to Abu Dhabi and prepared to end our time in Abu Dhabi, packing our specimens for shipment to the UK and Imperial College. Godfrey was ending his time in the field too. I had arranged to meet Sue King in Corfu and left for Greece around the 21st of April. Robin and Godfrey left in late April, Robin probably around the 26th of April.

Concluding remarks to this tale of high adventure

and emotive arm waving

Paddy and I couldn't believe the continuously calamitous events that confronted us despite taking logical steps to avoid them. Paddy developed a most pessimistic attitude of mind while I started to half believe in karma. Persons as unsuperstitious as ourselves were developing a neurosis resulting from frustration and depression as the events that happened to us were overwhelmingly real.

At home in the UK I wouldn't "bother God" and even in Abu Dhabi when events made me feel like sending telegrams to heaven, or when I shook my fist at the sky and told the ancient Greek deities of the Olympian pantheon to trot off elsewhere, I did so with a certain feeling of disbelieving humorous indulgence. However no escape! Here were we, Xristopher of the Irish ascendency and descendant of a long line of sea captains out of Liverpool, most of whom were pirates, and Pads of a long line of profligate baronets were crumpling before the profound effects of the vagaries of the desert and the sea. The people around us undoubtedly colored our philosophies of existence and we came much nearer to appreciation of that existence. It would appear this philosophy is only applicable when one is on the edges of civilization. Christianity clearly has its source as a religion of the Middle East, where survival from its extremes is tough and requires self-reliance while the god of the suburban West nowadays is in contrast regarded as a 'Big Brother' who has little influence on their lives.

When I was writing from the shipwreck I knew that we were lost but safe. I supposed we would eventually reach civilization again and this is true or you wouldn't be reading this narrative. So using the imaginary Roman world of Robert Graves, before the Middle Ages, I and my companions found ourselves back to the world of signs and symbols and fate and omens where the Romans trotted about examining chickens' livers and getting upset if eagles shat on them, or did they? Actually I conjecture probably this would have been a sign you were going to be emperor or something equally important. Nevertheless in that desert with Paddy and Robin and Godfrey and Doug, we all became universal believers that in some perverse way of the deities, fate rather than ourselves predetermined our future. As it unfolded, our strange and tragic or fated tale was from the beginning all ups and downs, with mainly downs. I became resigned to the next calamitous event beyond my control. Paddy was unfortunately overcome by depression but who could blame him. He was pursued by calamity, never-ending mechanical breakdowns and tire bursts while others in the expedition seemed to miraculously escape most of these. Shipwreck anyone?

So the moral of this tale is that in a vast and inhospitable undeveloped region as was the then UAE of 1964, all help came from within oneself; if one's boat was wrecked, you might get to die; or if your car broke down you again might well might die. We were immune to thinking about, or even fearing, the future but only the now. There was no escape unless we prepared for any eventuality. However fate, often an unforgiving fate, would ordain otherwise. Hence the characteristic shrug of the Bedu's shoulders, and the phrases It is written, or If God wills it. A person's whole existence quickly becomes geared to this attitude of mind, from the most elaborate plans down to the smallest move one makes.

One's life in the UAE of old was so dependent on careful and minute planning, that when this collapsed, as it almost inevitably would, for a whole score of unforeseeable circumstances, then fate or God was brought forward as the cause and was the direction in which to turn for all hope. Pretty frightening way of living really, for without hope what is life and quite honestly who can really put their full trust in fate or God blindly. God exists in the mind of those living on the edge of civilization. The suburban dweller can ignore an all-encompassing God but the nomad cannot. Neighbors and companions are not to be ignored for help given to them may be returned to oneself. The cost of help one provides can be great materially but still it makes one believe in oneself as a large wide generous person. Each individual in the desert is an oasis of self-dependence and help. Each can empower and each at the same time is potentially the most humble supplicant. You can feel alone in a town since there is no help if you know no-one but far off in the desert, a wild terrain in Scotland or on a rough sea, though you are hundreds of miles from anyone else, your nearest companion is potentially a friend.

To keep in the cool and avoid the overwhelming heat, our Imperial College field trips were scheduled from October through April. However we were unable to shield ourselves from the effects of Shamals which had a devastating effect on our field work in 1963 and it is no mystery that we had such bad luck. The phenomenon we experienced are quite common. Ironically it was in 2007 that I came to realize working with Gene Shinn, and Xavier Jenson that the five day events we experienced in 1963 in Abu Dhabi with high but irregular rainfall, each lasting no more, were common. They matched today's Abu Dhabi annual occurrence of infrequent winter to early spring rainfall of no more than 5 days. Today's northern Shamal winds normally last no longer last no more three to five days matched with rain and dust events. The dust and clouds of silty-sand seen from our boat extending up several thousand feet obscuring the coast so we lost direction are common. It was not surprisingly that travel by sea in our 17 ft launch became a challenge. Others working on land, air and in the sea around Abu Dhabi experience what we had. During similar wind events, several Southwest Asia international airports have recorded winds as high as 49 mph (43 knots) driving dust over large distances downwind. This sandblasting effect strips paint from cars. Xavier, Gene and I presented a winning an SEPM prize for best poster on similar events using satellite images with dust from the storms settling in the sea triggering pelagic blooms of lime mud.

Despite Paddy's and my inability to spend more than around three weeks in field work we both collected samples and enough physical observations from Abu Dhabi to write our PhD dissertations and successfully defend them to acquire our doctorates and launch successful careers. Godfrey Butler acquired a M.Sc. for his work with Imperial College and Robin Waddell, supported by his newly-established wife Sonia, acquired a BSc First class hons in Chemistry at the University of London.

References

- Butler, G. P., 1965, Early Diagenesis in the recent sediments of the Trucial Coast of the Persian Gulf: Upubl. M. Sc. Thesis, University of London. Pp. 162.

- Kendall, C.G.St.C., 1966, Recent carbonate sediments of the western Khor al Bazam, Abu Dhabi, Trucial Coast, Upubl. Ph.D. Dissertation, University of London. Pp. 273.

- Skipwith, Sir Patrick A. D'E., 1966, Recent carbonate sediments of the eastern Khor al Bazam, Abu Dhabi, Trucial Coast, Upubl. Ph.D. Dissertation, University of London. Pp. 407.

- Waddell, Robert (aka Robin), 1967, BSc First Class Hons, Chemistry, University of London

Conclusion

Truth and justice prevailed despite our misinterpreted and sometimes misspent student days.