Champion Godparents

But who were they anyway? I was well into sentient childhood before the question cropped up, and it took a long time before anything like the full answer emerged. How could something so straightforward be subject to such reticence? But of course my father cared little about such matters, and my mother was always deeply secretive about them, for fear something might emerge that was somehow discreditable to herself.

The answer as I now understand it, was that Aunt Frances had been my godmother and that Ralph and Wynne Champion had been joint godparents. Aunt Frances made perfect sense, as she had always sent birthday cards, and when we were up in London had treated me to a Knickerbocker Glory (2/6d!) at Fortnum and Mason in Piccadilly, and on another occasion had taken me to see War and Peace at the Leicester Square Odeon, as a result of which I instantly fell in love with Audrey Hepburn as Natasha. (Frances it was who subsequently took me to see Gigi, I think, as at some point Leslie Caron became my alternative ideal.) And there were all sorts of other occasions of auntly support and encouragement, and a very kindly bequest in her Will.

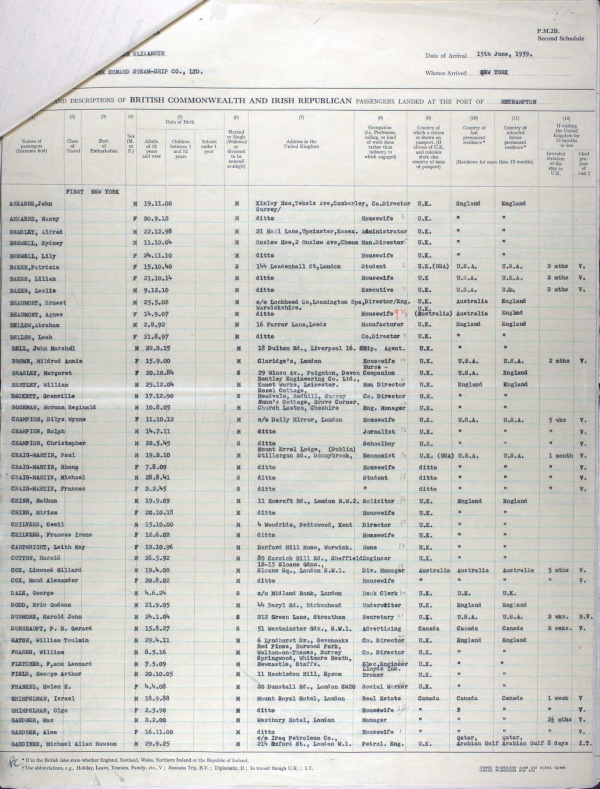

But who were Ralph and Wynne Champion? I have really only just found out, and it's actually rather interesting. They were definitely friends of Katie rather than of William (aka Bill at that time), and I guess that Wynne had been a colleague of Katie in the Alan Good organisation during the war (which was still in progress when I first saw light of day). Ralph was a journalist, based at that time in Leicestershire, but was destined for much wider horizons, rising rapidly through the ranks to become Chief of the Daily Mirror New York Bureau, as this narrative will reveal.

Misinformation

One of my earliest fully-fledged recollections (ca 1948) is being taken by my parents to visit the Champions, somewhere or another (maybe in London – perhaps they were about to head for New York), but certainly at a rather grand residence with three floors centred round an imposing helical staircase, with a very 'long-drop' stairwell in the middle, right down to the ground floor.

Their son Christopher and I, of much the same age, were parked on the top floor, with an injunction to play together nicely. Well perhaps we did for a while, but ran out of inspiration quite quickly. But the old-fashioned gas fireplace caught our eyes, and perhaps we'd never seen such a thing before, so we investigated.

It comprised half a dozen or more vertical white fire-clay strips of ornamental design, enclosed behind a thin metal grill, all set in a rectangular surround. It's almost impossible to find a good likeness on the internet, but this illustrates the general idea of the fire itself.

Well, this was a challenge, but it hadn't been lit, so pretty quickly we worked out how to extract the strips, and then the obvious next step was to drop them one by one down the stairwell. My, what a satisfying smash as they each hit the ground floor far below!

But retribution was swift and savage, especially for Christopher, who was sent to bed without any tea. I, however, remember sitting smugly at the tea-table and saying to all and sundry "I'm a visitor, so I can have cake, and Christopher can't!"

What an odious little beast...

In the next few years that followed, I was more than once informed that Christopher Champion had pushed some implement into an electric socket and been badly hurt. Well, at that age I couldn't connect this with our earlier escapade with the gas fire, but perhaps this was a rather lurid Awful Warning to beware of electricity as well as gas.

But my mother also casually mentioned that Ralph and Wynne Champion were my godparents. That of course meant next to nothing to me, but it was obvious that she felt it was Time I Knew. I do still retain a rather battered silver christening bowl, inscribed with my initials and date of birth, but I've never been told who had contributed it. Indeed, I rather think it only came to light when I was executor of her estate, and so it must have been from them rather than from Frances.

The next piece of this retrospective jigsaw emerged in my mid-teens, when Ralph, Wynne and Christopher paid a visit to England together, and Katie marshalled my brother Simon and myself for a get-together – and I'm quite sure she now said that Christopher suffered from cerebral palsy. Ralph wisely had a meeting with the Daily Mirror top brass to attend, so we didn't get to see him and I don't remember anything much about Wynne, but I certainly didn't notice anything the matter with Christopher.

| # | Individual | Spouse / Partner | Family |

| ‑1 | Ralph Champion (14 Jul 1911 – 10 Jun 1987) executive journalist Probate |

Dilys Wynne Davis (11 Oct 1913 – 1994) (m Q1 1935, East Glamorgan, 11a 1216) Grave |

Christopher Champion (b 23 May 1945) |

| |||

And that's the last that Simon or I ever saw of them. But Ralph would almost certainly have retired from the journalistic treadmill in the early/mid 1970's – the newspaper business takes no prisoners. He and Wynne resettled in Winchelsea, a quiet backwater of East Sussex just a few score miles from Chichester.

In fact, an article in Private Eye, 31 Oct 1975, alleged that Ralph, referred to as former Chief of the Daily Mirror's US Bureau, had held his position as a sinecure and received a "swollen pension" from the Daily Mirror. Well, lucky him – at least he got it before Robert Maxwell misappropriated the entire pension fund.

Some years later, in 1986, Katie moved from Oxford to Chichester, and picked up the threads with Wynne again. It would have been fascinating to listen-in to her reminiscences of Ralph's career, but (as my wife Sonia so perspicaciously remarks) Katie didn't like to share her friends.

Alas, at this distance in time, there are just two examples to be found of Ralph Champion's reportage

Demon Drink

The Welsh have a reputation for gloomy Sabbath sobriety and piety, but after all, their Celtic origin does predispose them to the occasional bender, as witness Dylan Thomas' notorious eighteen straight whiskies and Richard Burton's seventeen consecutive dry Martinis. And of course the precarious trade of journalism, like those of acting, politics and the legal profession, seems to require the untiring reassurance of alcohol. And in this respect, despite his unchallenged preeminence in the Daily Mirror New York Bureau, Ralph Champion was evidently no exception.

Indeed, that same article in Private Eye referred to above, also described an alleged drunken incident involving Ralph and Hugh Cudlipp at a public house in Rye, just a couple of miles from Winchelsea.

But there's a wonderful vignette of his personal oddities, possibly enhanced by liquid lunches, in the memoirs of Mike Molloy, editor-in-chief of the Mirror group.

The Happy Hack – A memoir of Fleet Street in its Heyday,

by Mike Molloy, published by John Blake 2016

Today, Fleet Street is just a term for the newspaper business. But not so long ago it was a real place. Each paper had its own favourite pubs, its own extraordinary characters, and its own stock of legendary tales about the triumphs and disasters that had befallen friends and enemies. It was the Street of Dreams; the Street of Adventure; the Street of Disillusion and, in the end, sadly, the Street of Profits. But once upon a time it was a place of magic....

Mike Molloy began in Fleet Street as a messenger boy on the Sunday Pictorial, and subsequently worked as a cartoonist, page designer, feature writer, and features executive. Eventually he was appointed the thirteenth and youngest editor of the Daily Mirror, a post he held for ten years. To his surprise, as he had opposed the take-over, when Robert Maxwell bought the Mirror, Maxwell made him editor-in-chief of the group...

This excerpt is a vignette of the legendary Ralph Champion, head of the Daily Mirror’s New York office, quite possibly the prototype of Private Eye’s semi-mythological Lunchtime O’Booze. I feel modestly proud to have been his godson...

Chapter 21

GO WEST, YOUNG MAN

The day Edward Heath called an election in early 1974 (there would be two general elections that year), Sydney Jacobson and I were having lunch with Hugh Cudlipp, so it rather dominated the conversation. Hugh was enjoying his retirement but we could see he was going to miss leading the Mirror's campaign. Heath had made a mistake in taking on the miners before he had sufficient coal in stock to feed the power stations, so the country had to endure the three-day week.

We traded headline ideas for the front page for the following day and Hugh suggested, AND NOW HE HAS THE NERVE TO ASK FOR A VOTE OF CONFIDENCE. It was the clear winner, and became the last headline Hugh was to ever write for the Daily Mirror. To Harold Wilson's own astonishment, Heath scraped home.

After the election Sydney decided I should go to America for a month on an educational trip. Starting with a couple of days in New York, I was going on to Washington, then Los Angeles, San Francisco, Las Vegas, Dallas, New Orleans, and back to New York, where Sandy would join me for a final week.

Mirror staff visitors to New York always trod carefully because the head of bureau was Ralph Champion, a man who had created an enduring legend for being difficult. Ralph looked like an ambassador. Tall, silver-haired and elegantly dressed, he had lived in New York for more than twenty years and was proud of the fact that he hardly ever spoke to Americans.

His entire focus in life was to keep Hugh Cudlipp happy and poison anyone else's chances of getting his job. Champion and Cudlipp had worked together in their boyhood; hence Ralph's posting to one of the glittering prizes the Mirror had to offer.

To be a member of the New York staff was a fabled appointment, even with Ralph as the boss. And there was a cost-of-living adjustment to the salary that meant staff reporters could live in some splendour. Because of the time difference, copy had to be sent early in the day, meaning evenings were usually free.

The junior member of Ralph's staff was to go early each day and secure a special seat in Costello's, the bar used by the press corps. Costello's was a low-ceilinged, crowded saloon where the walls were covered with drawings by James Thurber. At the far end of the bar was a restaurant presided over by an ancient Austrian called Herbie, known as the world's worst waiter.

The seat reserved until Ralph arrived was at the bend in the bar where the telephone on the wall was located, so the office secretary, Barbara, could patch any call from Hugh Cudlipp to Ralph's seat. Since Hugh called only about once a year it said a lot for Ralph's caution.

It was one of Cudlipp's quirks that he never visited New York. He pretty much limited his frequent world travels to locations that were once part of the British Empire. Australian, South African and Canadian newspapers all look to Fleet Street for their style, so Hugh was a mighty figure among Commonwealth journalists. In America he was unknown; the only British newspaper Americans had ever heard of was The Times.

Since I was from London, I was automatically regarded by Ralph as a potential enemy, but when I finally convinced him I was not there to seize his empire he became less hostile. He even became cooperative when I told him I wanted to stay at the Algonquin Hotel.

'Why do you want to stay there?' he asked puzzled. 'It's full of writers.'

John Smith, an old hand in the New York office, explained how weird Ralph was. 'He's a hypochondriac,' said John. 'He called everyone into his office one morning and said he was suffering from a dreadful disease he'd read about in Time magazine. A major symptom was that one foot swelled painfully.

"'I've got it," he said in a pitiful voice. We all looked down and saw the shoe on his left foot was one belonging to his son and was two sizes smaller.'

Smith continued: 'He does have one genuine condition, though. He has a compulsion to jump from high places. He has a fear that he'll come back from lunch and throw himself from the window. So he arranges the furniture so that he won't have a direct run to the window. Tony Delano [then another Mirror staff writer] used to wait until he'd gone and then rearrange it to give him a clear passage.'

It was in Costello's that I first made friends with Brian Vine of the Daily Express, who invited me to have lunch. 'Mind your manners,' Brian demanded of Herbie. 'My companion is from London and used to proper service in restaurants.'

'Velcome to New York, young man,' said Herbie in a thick accent. Vot can I get you?'

I ordered a hamburger and Brian Vine said, 'Poached salmon - I love poached salmon. I'll have that.'

'Ve don't have no poached salmon,' said Herbie.

'Then why the fuck do you put it on the menu?' bellowed Vine.

Herbie looked down on him with a gleam in his eye. 'Because I know you like it,' he said.

Later, I stopped at a jewellery store in Grand Central station and asked the proprietor if he had any cheap watches. It was as if I'd struck him a blow in the face.

'Sir,' he answered, 'we only have inexpensive watches.'