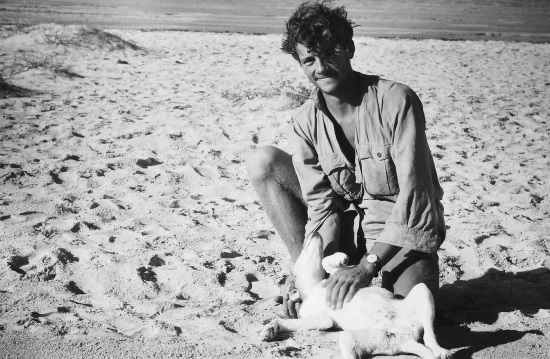

Hawking and coursing for desert hare

Like people the world over who lived at just one remove from hunger or even starvation, the desert Arabs of Thesiger's time were happy to follow Dr Johnson's vigorous example (as reported by Oliver Goldsmith) : There is no arguing with Johnson : for if his pistol misses fire, he knocks you down with the butt end of it.

So the hunter was equally happy if the hawk missed the hare but the saluki nabbed it, or, if a saluki wasn't an option, then an ambitious mutt did the job.

I've used the past tense as I wouldn't suppose the present tense would apply any longer – why hunt your protein if you can buy it ready-prepared at a gigantic air-conditioned shopping mall? We almost all succumb to such soft options ...

But in 1983 Sheikh Zayed, an ardent wildlife conservationist, founding president of the UAE and ruler of Abu Dhabi, took hares off the menu anyway, banning the hunting of the creature.

But how do desert hares subsist in such arid and inhospitable places? For one thing, they don't need to drink, as also revealed below.

Abu Dhabi, UAE

UAE Edition

International Edition

Tom Duralia

September 27, 2009

The UAE's desert hare is something of an enigma: it digs no burrow but survives the heat of summer on the surface of the sands.

Desert hares

Chris Drew is burdened with a lingering, nagging hypothesis, an untested carry-over from thousands of hours spent observing, tracking, trapping, measuring, implanting, de-ticking, thinking about and, ultimately, falling in love with the desert hare in the sands of the UAE. And it's all about the ears.

They are huge. Much larger in relation to body length than the pairs on any other species of Lepus. And even within the snarl of its own taxonomy – and there are some 80 subspecies on the books – the ears on the Abu Dhabi version of Lepus capensis omanensis, at 26 per cent of its length, probably rank right near the top. An average human male with such a ratio would be sporting a set 46 cm long from lobe to tip.

Along with better hearing, the conventional thinking is that big ears have a lot to do with keeping cool, something exceedingly important for a smallish animal that, for whatever evolutionary reason, lives its life on the surface of an unforgiving desert. Dr Drew, a biologist, would say – in fact, has said, in his doctoral dissertation – that the hare "lives on the very fringe of survivability" with respect to its habitat and above-ground habit. He sometimes wonders why a desert hare hasn't evolved with a real ability to burrow, like rabbits. Life would surely be easier.

On the other hand, you should see them go; hares have traded off any structural or muscular aptitude for tunnelling in exchange for explosive speed and agility. "These are extremely fast animals," says Dr Drew. Quite how fast, he does not know, but some reports say they can reach 70 kph. Suffice to say: "They're nimble. They're slender. Their bones are actually curved to give a natural springiness, whereas the bones of burrowing animals are short and very rigid for lateral strength.

"There is no lateral strength in a hare's bones. They would snap." Also unlike rabbits, hares are born complete with fur and with eyes wide open and are ready to go within a few hours of hitting the ground, an essential trick for any prey animal born in the open. Large mammals, such as the oryx, also don't burrow, but their size gives them a real advantage over the hare when it comes to dealing with the desert heat and loss of water through evaporation; having a small surface area relative to a large body means it takes them longer to heat up than it would a smaller animal. At the other end of the scale, the smallest desert mammals have a completely different solution to the problem. They've taken their large-surface-area-to-volume ratios safely below ground, living out the blistering daylight hours in the high humidity and comfortable cool of their burrows.

The jerboa, gerbil and jird are fine examples. Between the big and the small, the evaporators and the avoiders, in a sort of no man's land, as Dr Drew tells it, sits the superbly camouflaged desert hare, probably hunkered down somewhere under a scrawny saltbush. The UAE's hares are the smallest in the world, averaging only 1kg in weight. Sometimes they scrape a little sand here and there, and occasionally they may borrow a burrow from a lizard or sand fox as opportunity allows, but for the most part it is just them, the diffuse shade afforded by the bush, and an ambient temperature that regularly creeps up to 48° C in the summer.

So how do they keep their cool? Jump to the black-tailed jackrabbit of the deserts of the US and Mexico. At about two to three times the size of our hare, it's not a perfect comparison, but one at least for which a little heat-regulation research has been undertaken. These hares die if their internal temperature hits 45.4° C, so it's imperative they stay cool. Panting and sweating might help through evaporative cooling, but one study demonstrated that were the black-tail to employ such a technique – which it doesn't – it would need to replace about five per cent of its body weight every hour with fluids. Not really a viable strategy for a desert-dwelling mammal.

Instead, the black-tail uses its paper-thin ears, along with a few other adaptations, to help to dissipate the heat. As the days warm up and the jackrabbit's temperature starts to rise, it brings its ears to full attention, somehow also increasing the flow of blood to them. Perhaps with a little wind to help, some unwanted heat is radiated away, the hare's brain stays below the critical temperature, and the buck or dam lives to hop another day. But when it comes to the desert hare, Dr Drew's loyalty to the ear-cooling theory goes only so far. Maybe it's fine for the larger jackrabbit living in the somewhat cooler North American desert, and maybe it's even fine for our hare through part of the year at certain times of the day. But when summer's furnace is fully stoked and it's 48° C in the Sweihan shade, he hasn't seen many hares twitching their upright ears in the breeze.

At that temperature, he says, ears simply can't work as radiators. They will be net absorbers of heat, the blood will heat further and, well, it just won't work. In fact, in contrast to the ears-up attitude of the jackrabbit, the UAE's desert hare tends to sit out the intense heat with its disproportionately large ears drooped and draped in a gentle curve that almost covers its compact body. Even in this posture the ears would be absorbing heat, says Dr Drew – unless the desert hare has evolved some way of shutting off the flow of blood to its ears, in effect turning them into a custom-fitted, light-reflecting parasol.

But someone else will have to confirm the theory, a thought Dr Drew, now a sustainability manager for Masdar, would find quite gratifying. His dissertation and expertise on the desert hare would be at their disposal, an advantage not available to him back in 1996 when he first arrived from Liverpool to work on his PhD in a collaborative project between the University of Stirling, Scotland, and the National Avian Research Centre in Abu Dhabi, and began sifting the sands for the presence of hare.

Back then, nothing was really known about the desert hares in the UAE, or anywhere else for that matter, despite the animal having a distribution from the Cape of South Africa to southwestern Europe and all the way over to eastern China. Before he could begin addressing any pressing ecological questions, Dr Drew had first to assemble some basic facts about the animals: Where did they live? How abundant were they? What did they eat? It turned out that the hare has its paws in just about every corner of the UAE, except the mountains. In Abu Dhabi, he found them, or their pellets, in the dunes of the Empty Quarter, on islands and even in barren saltflats, where vascular plants suitable for food or shelter might be found only every few kilometres. But wherever there was passable cover, there were signs of the hare.

They are nocturnal, leaving their scrapes to feed and breed with the setting sun. They meet their moisture and nutritional requirements by eating a variety of plants, including succulent saltbushes, and are known to tolerate water at up to six per cent salinity, which is slightly less than double the usual concentration in seawater. He hasn't seen them drinking seawater, but notes that the hare "must have some pretty serious kidney action going on" for that capability.

They also absolutely love a plant named Limeum arabicum: "It's like candy to them," Dr Drew says, and wherever he has found the plants, he has found evidence that hares have been snacking on them. Desert hares are most likely to be courting in the winter months, but are capable of giving birth all year long and dams can become pregnant while still nursing the one or, more rarely, two leverets recently delivered. Gestation takes just 42 days.

They're also extremely secretive with their young. Despite endless traipsing through the hare's habitat during his seven years of detailed research, Dr Drew only once saw a newborn. He has, however, witnessed some of the pugilism more famously displayed by the "mad" March hares of Europe. The ear-ripping, fur-flying fisticuffs tend not to be male-versus-male bouts, but usually involve the larger female resisting the advances of some fervent buck or, perhaps, testing his mettle as a satisfactory mate.

Dr Drew once caught a male and female together in one of his live traps and, while not a deadly encounter, the result certainly wasn't pretty: "The male was more or less scalped, the female pretty much undamaged, but when I released him he was fine." These are, he says, "very tough, very resilient animals" and the biggest threat to their well-being certainly isn't each other, nor any of the host of natural predators, such as the eagle owls and foxes, that take them when they can. The biggest danger to the hare is human disturbance in its many forms. He saw some of the effects first-hand when one of his study sites, in the northeast of Abu Dhabi emirate, was destroyed almost overnight when a camel camp was set up in the vicinity.

Whereas previously one or two camels a day had passed through the site, now there were 500 milling about, devouring the fragile plant life he had painstakingly documented and on which the hares relied. Overgrazing of their food and shelter would have been enough to drive the hares away, but human encroachment – and the waste it left behind – was also followed by the arrival of aggressive feral cats and higher densities of red foxes. In no time, all the hares were gone.

In the past, Bedouins also hunted the hare, using falcons in winter or saluki dogs at any time of the year to put some meat on the table, but in 1983 Sheikh Zayed, the founding president of the UAE and ruler of Abu Dhabi, took them off the menu, banning the hunting of the creature. "He was very much a wildlife conservationist," Dr Drew . "The story I heard was that it was thought that desert hares, along with other wildlife species in the desert, such as gazelles, were in decline, and he felt that you shouldn't hunt them then if you don't know anything about them."

Today, the desert hare does not seem to be in much danger; in fact, it is probably one of the animals most likely to be seen by a casual visitor to the desert. But, even with Dr Drew's thesis in hand, there are still enough fundamental questions left about hare physiology and ecology to keep a cadre of doctoral students busy, and he hopes others will follow in his footsteps. He would certainly recommend the experience. Settled in Abu Dhabi with his wife and two young children, he has found the desert, especially off the beaten track, to be one of the most beautiful places in the world.

And as for its long-eared inhabitants, well, "I love them. I just really love them".

The pictures that follow were also taken during the 1962 Imperial College expedition, and are pretty well self-explanatory.