Doug Shearman

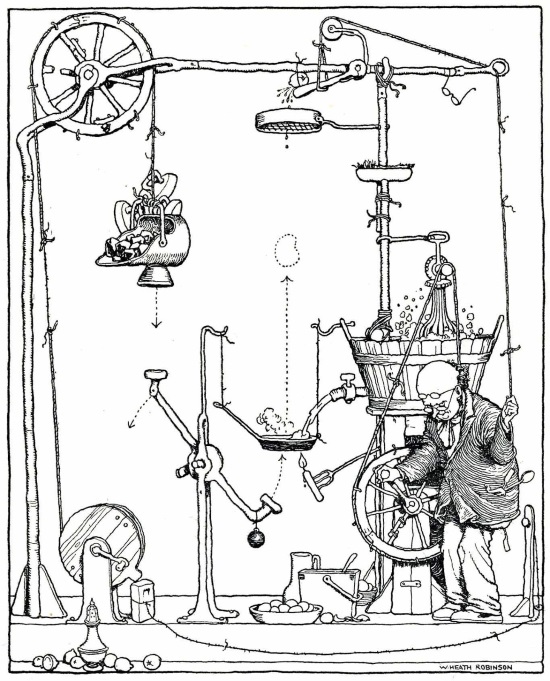

In the dear dead early 1950's, when the world seemed such an innocent, exciting and wonderful place, I was an avid reader of the stories of the unworldly Professor Branestawm, his housekeeper Mrs Flittersnoop, and his great friend Col Dedshott of the Catapult Cavaliers. I seem to remember that Branestawm invented, inter alia, a new sort of 'flu and a new way of breaking your leg. But he specialised in original and very complicated mechanised ways of achieving quite simple tasks that had been previously been done much more simply. This chimed with the British public's view of 'boffins' at that time.

The illustrator of these stories was W Heath Robinson, one of the most magical illustrators of all time – believe me, invest in Heath Robinson originals and you will never regret it. Like his even more talented contemporary Arthur Rackham he lived in an alternative world of his own creation, which as our own darkens will become ever more beguiling.

This unintended prolegomenon (these things just happen) leads to Branestawm's pancake-making machine, in which every phase of the process is controlled by the appropriate lever or string – mixing, pouring, heating, flipping and lemon-squeezing. Never mind that it'll take half an hour to set it going again.

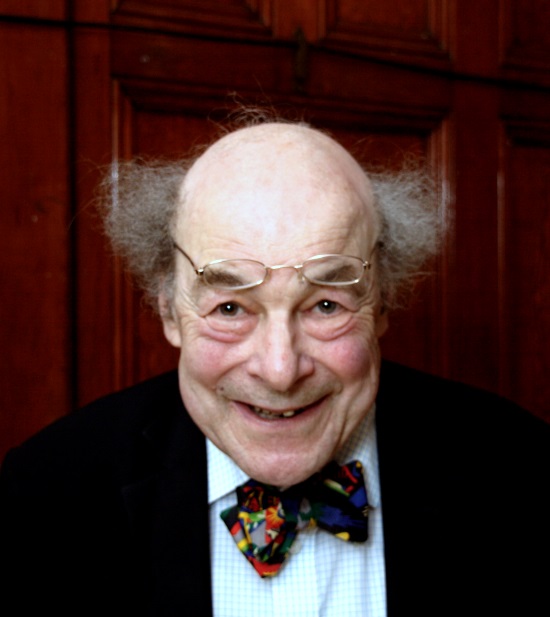

Wasn't Doug Shearman (equally unworldly, and, actually, later himself a Professor) just the very image of Prof Branestawm? Or, alternatively, the deeply lovable TV scientific presenter Professor Heinz Wolff?

His personal narrative was even stranger than fiction – as was the case for so many people born during the inter-war years. I didn't warm to him, but I hadn't walked ten miles in his shoes. He had served as a radio operator on the desperately dangerous Arctic convoys to Russia during the Second World War, and even were it simply for that he would deserve the utmost respect.

Not graced by English-language Wikipedia,1, 2 Doug Shearman nevertheless scored two prestigious obituaries from Canary Wharf.

Subscribe to the website and read the full obituary ...

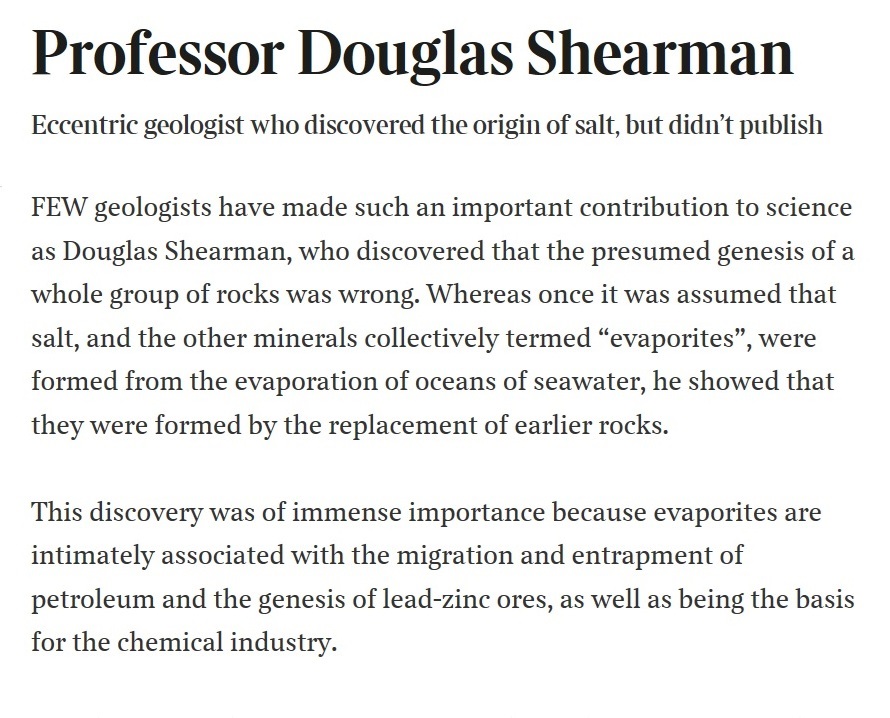

Professor Douglas Shearman

Unorthodox and inspiring geologist

Peter Bush

Thursday 22 May 2003

Douglas James Shearman, geologist: born Isleworth, Middlesex 2 July 1918; Assistant Lecturer, Imperial College, London 1949-51, Lecturer 1951-63, Senior Lecturer 1963-71, Reader 1971-78, Professor of Sedimentology 1978-83 (Emeritus); married 1949 Maureen Pugsley (two sons, one daughter); died Cassington, Oxfordshire 12 May 2003.

During his long career as a geologist at Imperial College, London, Douglas Shearman was a charismatic, enthusiastic, dedicated and unorthodox teacher and research worker. His lectures and seminars, illustrated by his own elegant and explicit diagrams, were stimulating and exciting. His view, now deeply unfashionable, was that it was his responsibility to show students how to think and not to fill their minds with endless details. Staff and students alike regarded him with admiration and affection, even those staff whose forms he failed to fill.

When Shearman was presented in 1984 with the Lyell Medal of the Geological Society by the President, Professor Janet Watson, she summed up his research genius:

"Two aspects of your scientific personality stand out. One is your genuine delight in a new idea and the way in which such an idea tends to dominate your thoughts to the exclusion of all else – the second, your ability to look at some very simple phenomenon which others have taken for granted and find something new in it."

After a primary education in Hounslow, west London, Shearman moved with his parents to Southend, where he completed his school education and, importantly, spent many hours exploring the Thames estuary and Essex marshes. After school he joined the Post Office as a trainee engineer. However his career was short-lived because in 1939 he was recruited into the Royal Navy. During his basic training in Dover he met in the Naafi Tom Pain, a young soldier who was examining a fossil from the chalk using a hand lens. Discussions over tea and doughnuts set Shearman on a career in geology.

After the Second World War, much of which was spent as a wireless operator on a minesweeper in the North Atlantic, keeping the lanes clear for the Russian convoys, chance played another trick. Shearman went to live in Chelsea and heard that at Chelsea Polytechnic there was a course in geology. He enrolled in 1946 and came under the influence of William Fleet, a remarkable and inspiring geologist who taught all the courses and ran all the field excursions. Shearman was awarded a first class degree and appointed Assistant Lecturer at Imperial College by H.H. Read.

Read, who recognised that the study of sedimentary rocks was becoming increasingly important, called Shearman in and said, "We need someone to work on and teach about sedimentary rocks, and I have chosen you." So Shearman became leader of the Sedimentary Subsection (initially of one), a post he retained until he retired in 1983.

Doug Shearman's research interests were very varied. They frequently resulted from a new look at an old problem or the connecting of two apparently unconnected phenomena. A big advantage he had was his ability to remember practically everything he read or saw. He would, for example, refer to a paper published in an obscure journal some 30 years earlier which was absolutely relevant. The downside of his ability was his tendency not to label any samples he collected or any photographs he took until they were required for publication.

During the late 1950s and early 1960s two major areas of research developed in the Sedimentology group under Shearman's direction. The first was a study of the limestones and dolomites found in the French Jura. Here Brian Evamy and Shearman developed micro-chemical staining techniques which helped unlock the cementation history of limestones, and Shearman, with other students, used trace element and other methods to elucidate the processes of dolomitisation and dedolomitisation of limestones. These techniques have since been used worldwide. The second area of research was on the inter-tidal sediments of the Wash on the east coast which was initiated by Graham Evans.

When the study of modern inter-tidal/supra-tidal sediment deposition was transferred to the arid environment of the Trucial Coast of the Arabian Gulf (now the United Arab Emirates), Shearman, Evans and their co-researchers defined what was to be called the Sabkha environment, and recorded the first example of Recent anhydrite. This study, together with one Shearman made in Baja California on inter-tidal laminated halite (salt) deposits, allowed him, working with John Fuller in Canada and others around the world, to re-interpret ancient evaporite sequences with great benefit to the oil industry.

In recognition of his work in sedimentology, Shearman was awarded a DSc and personal Chair in Sedimentology (the first in the country).