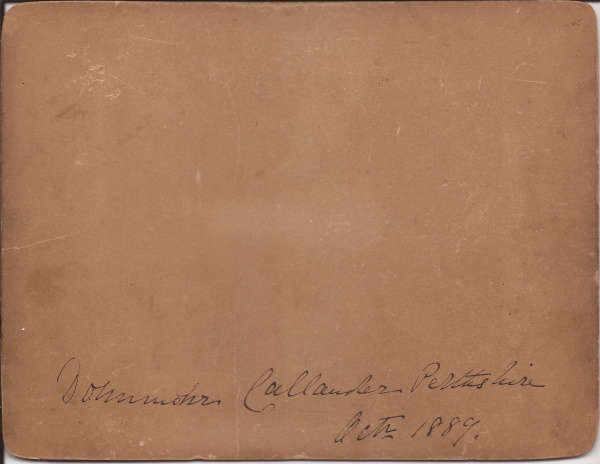

Dounmohr

After William Renny Findlay #1’s sudden death on 22 Feb 1872 his assets were sequestrated in order to settle his liabilities, pay his creditors and so on. But he left a wife Jessie Findlay (née Smith) and three unmarried daughters – Jessie Smith Findlay (b 22 Jan 1847) , Frances Mary Findlay (18 Dec 1861) and Annie Smith Findlay (b 8 Jan 1864) – all of whom would have been living under the paternal roof. What resources would they have had post WRF #1? Where would they live? Who would put food on the table?

The Married Women’s Property Acts of 1870 and 1882 may or may not have applied to Scotland, but I’m not remotely qualified to introduce those variables into the equation.

Fortunately, Jessie (née Smith) Findlay’s father and unmarried paternal aunt Anne had prospered from a joint business venture. And Aunt Anne just happened to pop her clogs a month or so later in May 1872. As one door closed, another one opened.

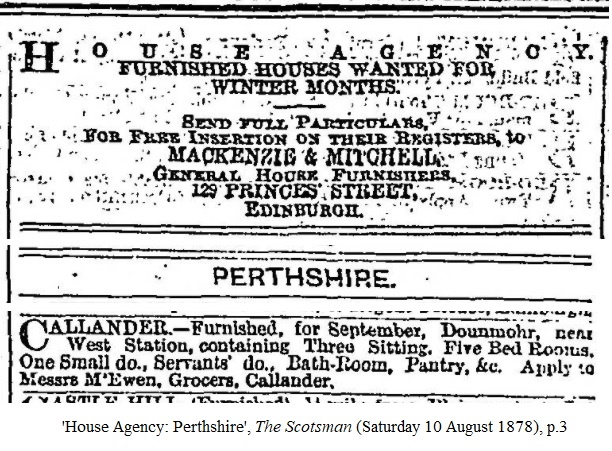

It’s very plausible that a substantial bequest from Aunt Anne enabled Jessie (née Smith) Findlay in due course to purchase a property large enough to accommodate Jessie herself and her three unmarried daughters. And by golly, Dounmohr was indeed capacious.

I believe that ‘Doun’ translates to ‘castle’ in both Scottish and Irish Gaelic, and Doun Mohr is the name of a substantial hill, crowned by the remains of a Roman fort, just a short distance from Callendar.

Perhaps it was at this point that Aunt Hannah Findlay (d 3 Aug 1897), just two years older than WRF #1 himself, joined the household – she seems to have particularly benefited from their father (Peter)’s will, as she was very deaf and had never married. She might quite possibly have been pretty well off, which always lubricates the wheels of family dynamics.

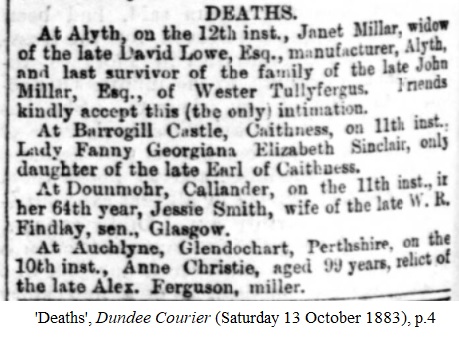

Jessie (née Smith) Findlay, to avoid confusion with her daughter Jessie Smith Findlay, could just be alluded to as Jessie Smith (and post mortem as relict of the late W R Findlay). In English usage (now largely abandoned by lesser breeds without the law) she would be addressed as Mrs W R Findlay, whether her husband were alive or dead.

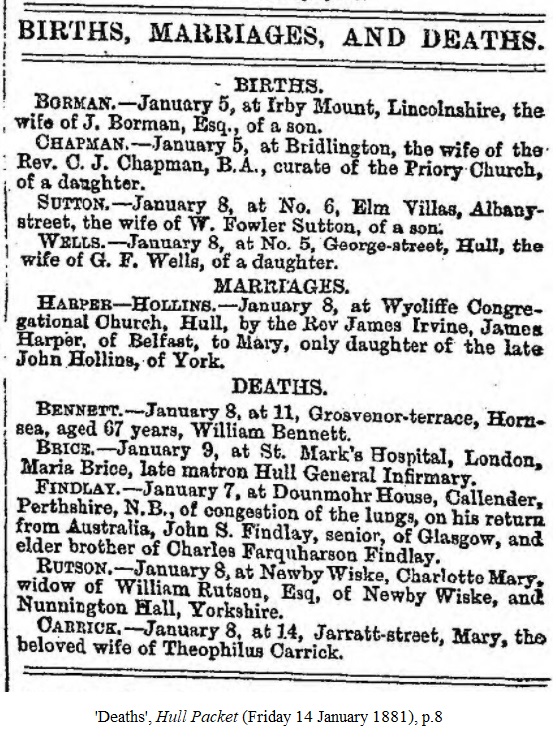

She was certainly in residence at Dounmohr at the time she was visited by her ailing second son John Smith Findlay, recently returned from Australia, who actually expired on the premises in early Jan 1881. (‘N.B.’ is an abbreviation for the rather pleasant anachronism ‘North Britain’, a term which sadly fell into disuse in the early 20th century.)

And as evident from the 1881 Census, Jessie Smith Findlay’s elder sister Isabella Muir, together with husband James and three or four children, were also living in Dounmohr at that time, though this may have been just a temporary arrangement!

In due course ‘The Mother’, as she was known, Jessie (née Smith) Findlay (d 11 Oct 1883) died just a month before her errant son Charles Farquharson Findlay (d 15 Sep 1883). She left Dounmohr jointly to her three unmarried daughter as co-proprietrices.

CFF had left his wife Annie and two young daughters Val and Hannah virtually destitute, and the family myth-mill has it (as passed down by Uncle Sandy’s account) that the two wee ones had to be rescued from their indigent mother, possibly by Jessie Smith Findlay, and carried back to Dounmohr to continue their upbringing.

Dounmohr in 1889 (as cropped and renovated)

The two children on the LHS are of course Hannah and Val,

the woman at the door is most probably Jessie Smith Findlay,

and next to her looks very much like Great Aunt Hannah Findlay.

Dounmohr was by now bulging at the seams. Too much so, perhaps, for Frances’ and Annie’s likings, and they might also have wanted to cash-in their shares of the ownership.

Val and Hannah’s financial security is said to have been underwritten by John Ritchie Findlay, proprietor of the Scotsman, and Sir John Traill Cargill, chairman of the Burmah Oil Company. There should in principle have been no impediment to buying-out Frances’ and Annie’s interests in Dounmohr.

The cosy ‘Elm Lodge’ version of events is that the two girls grew steadily and happily to maturity and eventual marriage and matrimony under the guidance of Jessie Smith Findlay, who then, job done, retired to the Gueritz household in Cheltenham.

Hannah was sent to a finishing school in Derby in order to lose her Scottish accent . There are some mildly amusing recollections, as per Aunt Jane, about the principal, Miss Louise Adams, who was in the habit of addressing each year’s leavers about a dream which occurred without fail at the end of every summer term. “Girls,” she would say, “last night I dreamt a dream, about a droopy people, whose heads were bowed and whose backs were bent. And I asked my Guide, Who are these people? And my Guide replied, These are the People with No Backbone, who have not the will to accomplish Great Things”.

“Girls,” she would continue, and you can guess the rest.

There was another one, about a sack of tapioca, which I’ll have to reconstruct the details of (not unakin to Hoffnung’s immortal Barrel of Bricks anecdote).

But I really don’t know for sure what transpired with the house, or its occupants, as that first decade of the new century led up to Val’s marriage to Elton Gueritz or Hannah’s marriage to Robert Waddell.

Hannah was a close friend of M E M Donaldson, and they might well have spent a good deal of time walking together in Scotland. Hannah had (largely) lost her Scottish timbre, though even in later years it sometimes peeped through. Donaldson had (according to my Aunt Jane) a dreadful accent acquired from her nannies in Croydon, known as ‘the speech of London’ – though not Cockney, let alone Estuarine, perhaps Dickensian intonation. It must have baffled her Scottish interlocutors.

When I was in my early teens Aunt Jane occasionally referred to Hannah having been being involved in the rougher parts of Glasgow as a social worker, "stepping over recumbent drunks on Saturday nights", which I couldn't imagine and only half-believed. In retrospect, and in the light of her close connection with the Rev Richard Free, I can now picture her in such a context, After all, Salvation Army ladies fearlessly ventured into the vilest premises to spread their message, so why shouldn’t Wee Grannie (as Aunt Frances often referred to her affectionately) have done likewise.

And thirdly, there was Robert the caustic, sardonic, irreverent and immensely intelligent marine engineer, my paternal grandfather-to-be whom she had probably first met in Ardeer via Edwyn Alfred Findlay (Cousin Eddie). That must have been quite a tentative courtship, but at the age of almost 30 she travelled unaccompanied by steamer across the Atlantic, and by railroad across the prairies until the rails ran out, and then by covered wagon until she at last made contact with him in Seattle where he was working for the US Navy.

Dunmor

youtube.com/watch?v=PuCtWhekzDs

Dounmohr was evidently rebranded a while back as Dunmor, and for some time past has been marketed as a holiday letting for the well-heeled end of the UK holiday business, as witness the impressive weblinks at the top.

The exterior is instantly recognisable, though I don't suppose that our revered Findlay ancestors would now recognise (let alone approve) the lavish interior décor. Should there ever be a grand gathering of Clan Findlay, however, this would be quite a venue!

But how had it fared between the late nineteenth century and the early twenty-first century? Who had come and gone? Uncle Sandy’s profile of his mother Hannah Findlay states that it had been ‘owned by uncle John Smith Findlay and his wife Ellen (née Benet); they cared for his mother Jessie Findlay (née Smith) until her death on 11 Oct 1883, so there was room to assume the additional responsibility [of accommodating the youngsters Val and Hannah].’

I think we have to discount both those statements regarding John Smith Findlay:

- His mother had bequeathed Dounmohr to her three unmarried daughters

- He predeceased her anyway!

Uncle Sandy also says, less incredibly, that ‘Dounmohr later came into the possession of the Christie family, shortbread suppliers to Balmoral. Miss Beatrice Christie had kind memories of the Findlays in 1968 as though 50 years had vanished.’

But, discouragingly, I can so far find no connection between

- Dounmohr and the Christie family,

- or the Christies and shortbread,

- or shortbread and Callander or Balmoral.

Aunt Jane often remarked that ‘Sandy got a lot of things wrong’, but was never specific. She also got a lot of things wrong, to my certain knowledge.

But absence of evidence is not evidence of absence, and things can turn on a sixpence – one small new fact, in itself insignificant, can undermine an entire way of thinking – the square root of 2, or the temperature difference down a waterfall, come readily to mind.

Sandy’s wonderful image that brings a fluidity to the eye and lump to the throat, however, is that the little girls’ nursery overlooked the railway and from the window they would watch and wave to the ‘engineers’ of the fiery single-wheelers as they pounded uphill to the Highlands.

Mohr and Mor

I am immensely grateful to cousin William Gueritz for these researches.

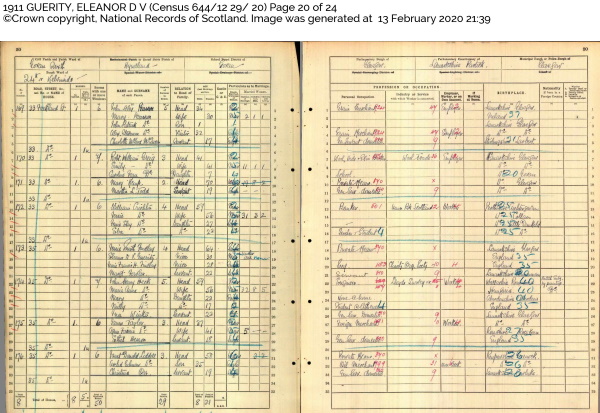

The 1911 Census information tells us that (quite surprisingly), Aunt Jessie, Val and Hannah now lived jointly in a single household (35 Falkland Street in the Govan area of Glasgow), possibly financed largely from Aunt Jessie’s private means that are mentioned. Hannah was in paid employment as secretary for a charity, and presumably Val, as a married woman, had some sort of housekeeping arrangement with her husband Elton (who was working abroad in the colonial civil service).

What the Census doesn’t tell us is for how long this mutually supportive household had been functioning. Perhaps more information can be chiselled from the as yet featureless face of that first decade of the 1900’s.

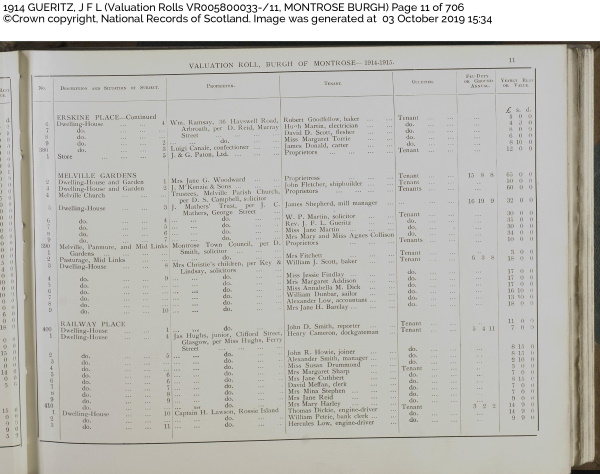

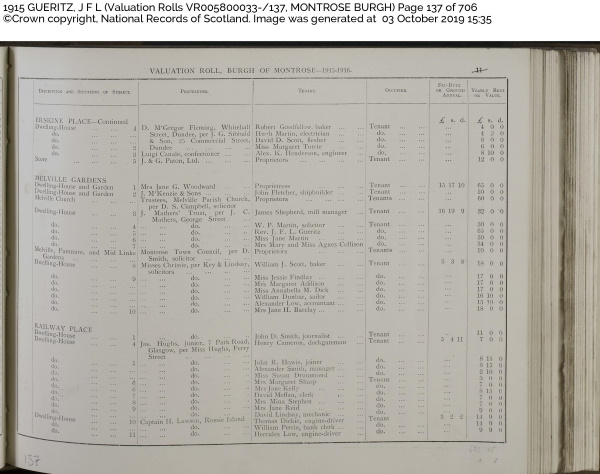

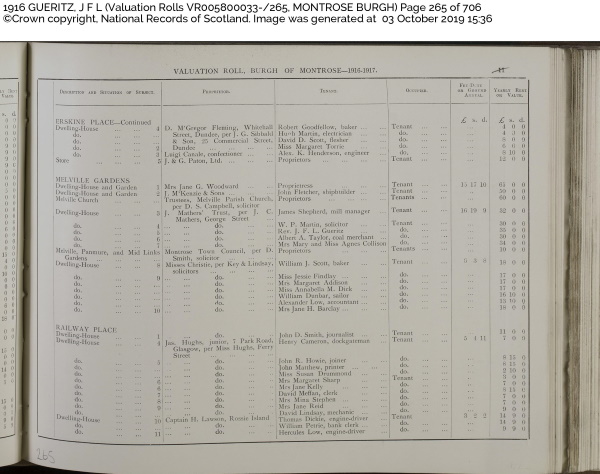

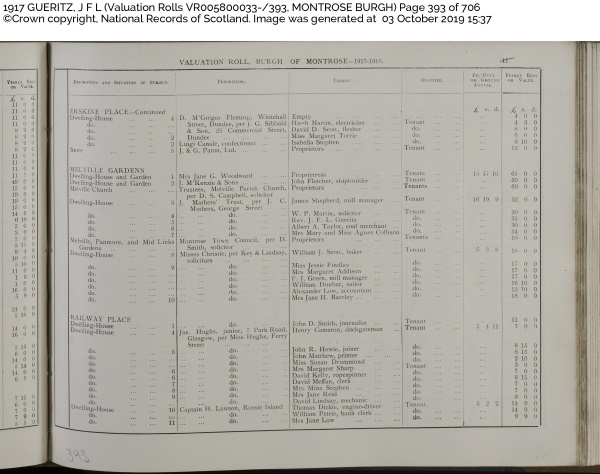

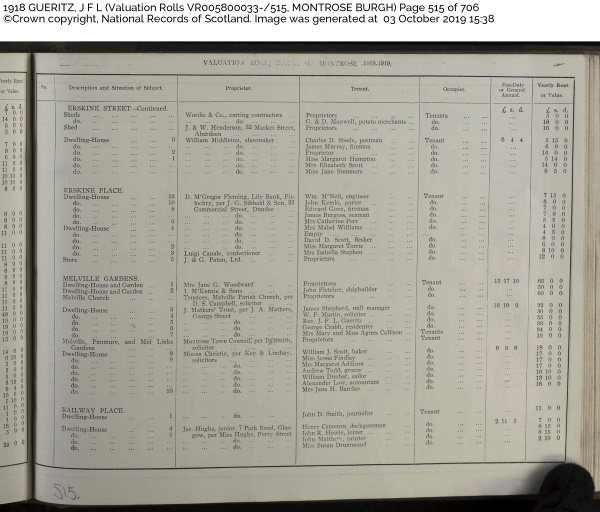

However, the Valuation Rolls reveal that, probably once Hannah had set out for America in late 1912 (wisely avoiding any truck with RMS Titanic) Jessie and Val (plus John, Val’s firstborn son, who had arrived in May 1911, soon after the Census) relocated to Montrose – Jessie at 9 Melville Gardens, Val and young John at 5 Melville Gardens, plus in due course Lucy, Val’s first-born daughter, who arrived in Aug 1915, and Eleanor who arrived in Nov 1916.

The occupant of 5 Melville Gardens, though, is recorded as the Rev J F L Gueritz (aka Fortescue) who was the Rector of St Mary and St Peter, Montrose (1909-1916). His wife Lucy had died in Sep 1915, and I’m not sure how he could have coped with the influx of a daughter-in-law and (progressively) three small children. He was evidently a very kind unworldly chap, by all accounts, but this was verging on the saintly.

In passing, it's interesting to note that the proprietors of 8-10 Melville Gardens were the daughters of (presumably) a Mrs Christie, and it might well be that she was the Beatrice Christie to whom Uncle Sandy refers.

TO BE CONTINUED

“My current narrative is this: Jessie, Val and Hannah (then John) lived together at 35 Falkland Mansions in Glasgow in 1911 (on Jessie’s terms); Hannah left in 1912 to get married and so Jessie, Val and John moved to Montrose (Val and John at 5 Melville Gardens, with Fortescue and Lucy Gueritz; Jessie at 9 Melville Gardens); and then in about 1919 they moved down south to a house named Lyncroft in Woburn Sands (Jessie probably stayed with Val; Fortescue in Aspley Heath/Guise). The earliest I can pinpoint their move to 1 Lansdown Parade is 1926 but I suppose it could have been late 1925. Jessie, of course, was there with them; while Fortescue stayed elsewhere. I have attached the various sources. It would have been helpful if I could find either Jessie or Val in the 1921 Census, but hélas they are not there, apparently.”