Charles Farquahson Findlay

(14 Aug 1853 – 15 Sep 1883)

The narrative that follows is reproduced from Alexander (Sandy) Waddell's invaluable summary in his biographical document FINDLAY WHO'S WHO.

[The conventional spelling of the eponymous clan for which Findlay was named is of course Farquharson, but for consistency I have stayed with the spelling adopted by my much-admired Uncle.]

Does this sound like the low-life of his later relatives' imagining, so lost to turpitude that he was stricken from the collective memory? Those of us in this era who understand how oppressively the law of libel discourages the crusading journalist from exposing the misdoings of people in public life, will readily accept the strong possibility that he was far more sinned against (by the sentence) than sinning.

It is fascinating to explore this further, to complete his rehabilitation into the bosom of the family. Indeed, it has only just come to mind that my father Walter once told me (when I was a bored and uninterested teenager) that there had been a custom in that era of English journalism for newspapers to employ a 'Prison Editor', whose function it was to take the rap and (if necessary) go to gaol, instead of the real Editor, if the newspaper were successfully sued for libel. If Charles Findlay had simply been the prison editor then he hadn't personally committed the libel anyway.

Well, that's a neat idea, and may well have originated from Walter's father Robert, who was of course a staunch defender of Charles Findlay's reputation. But in any case, that editorial was written by Charles Findlay – tanquam ex ungue leonem – so if it was libellous, he should have gone to prison – but it wasn't, so he should have been completely vindicated and absolved.

However, a very encouraging clue is given by a cutting, dated 20 April 1880, kept in the Wilberforce House Museum (Accession No. KINCM:1986.261):

and it speaks for itself: the people of Hull (especially "a number of Gentlemen") feel sufficiently outraged against this "attempt to blast the career of a talented young Journalist" to get up a fund towards his defence costs. And indeed the Manager of the Yorkshire Banking Company has agreed to act as Honorary Treasurer in this regard. Please remember that this was an era when high bank officials were regarded as the epitome of probity.

Lieut Col Saner had some years previously been forced to resign from the 4th East Riding of Yorkshire Artillery Volunteer Corps after differences with other acting officers and virtually all the volunteer force of 800 men, but still retaining his title of office. And much more recently, on 12 Apr 1880, Mr Saner was allegedly "publicly ridiculed in tabloid manner by an unsympathetic journalist, Mr Farquharson".

The Butterfly that Stamped

The Oxford on-line dictionary defines a prison editor as "An editor (of a newspaper) who takes legal responsibility for what is published and who serves any resulting term of imprisonment (late 19th century, now rare )". Was it ever otherwise? The very idea is in the same vein as the 'Police Hospitals' confidently espoused by the ghastly Margaret in Lucky Jim – a naïve conceit of the hopelessly unworldly, surely not Robert Waddell, much more probably my lovely but rather goofy Aunt Frances.

Even John Walter, founder and first editor of The Times had to spend almost two years in prison for allegedly libelling the Duke and Duchess of York.

I am now [May 2016] able to provide an infinitely better account of what was for Charles and his wife Annie much more akin to the Descent into the Maelström. But it will take time to assemble, and I will put it on-line gradually; existing material will be digested in transit.

May I start by reminding you of The Butterfly that Stamped, a charming tale told with mock-oriental verbosity by Rudyard Kipling, about an apparently unassuming creature that suddenly and decisively intervened in an intolerable situation, supported by a sympathetic and highly-born confidante.

Time Line

One of the many things I have learnt from this website, is that if one is fumbling for the best way of expressing an abstract concept, the Ancient Greeks can almost invariably supply a word for it. One of the many regrets I have about my misspent youth is that I elected for German rather than Greek in the fourth year at school.

(Somebody once asked rhetorically, "What did the Greeks ever do for us?". One might equally well enquire "What did the Germans ever do for us?". The war cemeteries stretching across Europe are mute testament to one aspect of the German cultural legacy. And apart from the incomparable JSB and LvB, German music was mostly composed by Austrians - and the 'v' in LVB stood of course for 'van' rather than 'von'. And incidentally, and entirely to their credit, the Swan of Avon is said to be the most highly-regarded dramatist in Germany. I like to get these things in the proper perspective.)

There were three major figures in the unfolding drama of the Hull Artillery Scandal: Lieut-Col Humphrey, 'Lieut-Col' Saner, and Charles Farquharson Findlay. In classical Greek drama, I believe, they would have been itemised as protagonist, deuteragonist, and tritagonist respectively.

But, ultimately, Humphrey and Saner were almost totally unscathed. Findlay, however, though a commentator rather than a participant, was crushed by Saner's vindictive malevolence. There is no record of Humphrey coming to Findlay's support and, for that reason only, we have to think the worse of him.

To me, coming without preconceptions to this episode some five years ago, the most extraordinary aspect of the whole affair was that the nature of Humphrey's alleged malfeasance was almost never made public, was never investigated judicially, and was never openly decided upon. In the same way that Dreyfus was a Jew, Humphrey was not a gentleman in Victorian eyes, and was unworthy of absolution. But was he bovvered?

Please click here for a chronological table of the Hull Packet's coverage.

Sowing the Wind

In the course of the magistrates' court hearing of Col Humphrey's summons taken out against Lt Baxter, there were intimations that certain of the junior officers in the 4th East York Artillery Volunteers were dissatisfied – and this of course was being subtly encouraged by Lt Col Saner, who had his eye on the position of Commandant for himself.

There is no doubt that Col Humphrey was a strict disciplinarian with all the men under his command, officers included, so the disaffected clique decided to destabilise him by throwing doubt on his overall management of the Corps' finances. In particular they had been spreading a rumour – not only within the Corps itself but amongst the general public – that a sum of £1,800, subscribed by officers and obtained from other sources, over and above the capitation grant, had been disposed of by Col Humphrey, and that he was unable to account for it.

Humphrey was well aware of these malicious mutterings and called a parade of the entire Corps to make a complete rebuttal of the allegations.

However, the conspirators had prepared a petition for an official investigation of their complaints, and Saner (careful not to actually compromise himself by adding his own signature) then presented it to the plumed hats in higher command.

The Army set up an official enquiry in camera to hear evidence seriatim from the signatory officers – plus Lt Col Saner – from Col Humphrey himself, and from the various members of the Corps who had responsibilities for keeping the accounts and disbursement of the funds.

Their report was published just seven weeks later. It entirely exonerated Humphrey of all wrong-doing, and stated unequivocally that Col Humphrey should order all the petitioning offices, including Saner, to resign their commissions immediately.

But Saner couldn't face the loss of social prestige that this humiliation would entail, and so he scurried off to see his slippery solicitor ...

Please see below for a chronological table of the events so far. Note that the dates against the links are of the editions of the Hull Packet in which the events were reported.

| 1) Fri 16 May 1879 | Rumours of Allegations |

| 2) Fri 16 May 1879 | Rebuttal by Humphrey |

| 3) Fri 13 Jun 1879 | Inquiry commences |

| 4) Fri 8 Aug 1879 | Exoneration of Humphrey |

Fateful Editorial #1

Findlay had been editor of the Hull Packet for a mere two months before issuing this shot across Saner's bows. In the interim, his warm and gregarious nature had made him many friends in the community at large, and his quick and lively intelligence had enabled him to grasp the local issues and comprehend the fluctuating fortunes of local trade and commerce. In other words, he had his finger on the popular pulse.

I don't yet [19 May 2016] have any notion of just what the baseless charges were that Saner levelled against his commanding officer, but I look forward to finding out! However, Findlay evidently underestimated Saner's ability to weasel his way out of the disciplinary action that had been imposed upon him, and ingratiate himself with whoever was temporarily in the ascendant in the Darwinian conflict between the Army C-in-C and the War Office.

Saner would not have enjoyed this salvo, but he was in no position to retaliate. And crucially, the proprietors of the Hull Packet, Henry Amphlett and James Holmes, don't seem to have made any objection to the content of this forthright editorial.

Hull Packet, 13 Feb 1880

'Echoes of the Week'

by Charles Farquharson Findlay

Although duly clad now in the garb of Lenten humiliation, neither this nor the appropriate meagreness of my diet can prevent me from having the rebelliousness of spirit to rejoice, yea, mightily, over the very latest snub that has been administered to the "Military Timber Merchant" from the War Office. Remembering the baseless charges which this volunteer officer and wood-trader advanced against his superior Commanding Colonel, it cannot, after all (I consider, upon second thoughts), be held rebellious to feel glad at any further confirmation as to the absolute sustainal of unspotted authority. I have never had the fortune or misfortune to serve under ex-Lieutenant-Colonel SANER in any capacity, and, from what I hear, I trust such a fate may for ever be spared me. Equally, if the consensus of current opinion be worth anything, I know not of any Volunteer Colonel I would sooner serve, even remotely, under than the Lieutenant-Colonel Commandant of the once more "Happy Fourth East York" should I at any time be called on to shoulder a musket for my country. Ergo, any remission of Mr. SANER's enforced resignation of his commission would be to me, like so many others of my fellow townsmen, most unwelcome tidings, as well as an actual injustice to those other officers who have been forced to resign. There need be no fears, however, as to the arrival of such tidings. The final fiat has now gone forth, and the London Gazette will indelibly seal the secession of the valiant warrior from at least one branch of Her Majesty's Reserve Forces. It would be unfair to hit a man when he is down, but then this one is also at present very much up; for, although in respect of his soldiering he has been reduced to zero, we must bear in mind how, in respect of his tremendous prowess as a Timber Napoleon, he has been hoisted into the Directorate of the Dock Company. And is not this a sop, a not inconsiderable quid pro quo? It is said that Mr. SANER intends to get some kind friend in the House of Commons to bring his volunteering escapade before the notice of that legislative assembly. I wish him joy of his sanguine freak, if it is really in contemplation; I commend him to the favourable consideration of Her Majesty's faithful Commons; but if he should by some strange chance get himself white-washed in the Lower House, who would stand surety for the equanimity of Duke George of Cambridge on getting one of his decisions reversed? Yet, of course, it must have cost the Commander-in-Chief many a painful throe, in the first instance, to dispense with the services of so distinguished a Volunteer officer. As to the nominal retention of rank, which I understand Mr. SANER seeks after, this is a concession by the Crown on a resignation after long and meritorious service, not a solatium for being virtually cashiered.

- According to his counsel-to-be, Mr Waddy, Findlay himself was an enthusiastic member of a Volunteer Corps, though I don't know which.

- The "Military Timber Merchant" and "Timber Napoleon" are scornful references to Saner's unconvincing efforts at private enterprise as a timber broker on behalf of the Hull Dock Company.

Fateful Editorial #2

Two months had now elapsed, and it had become blatantly obvious that Saner's solicitor Rollit had prevailed upon the good-natured outgoing Secretary of State for War to retain his military rank of Lieutenant Colonel, and the right to wear his uniform on ceremonial occasions – very important of course to a socially-insecure individual in that caste-conscious era.

But that highly-prized privilege wasn't to be extended to the junior officers that Saner had persuaded to support his allegations against Lieut Col Humphrey. They were permanent relegated to civilian status. And I think this is what particularly riled Findlay, and triggered his blisteringly sarcastic broadside in this next editorial. Ridicule is what really wounded the sensitive Saner, and off he went to the ever-supportive Rollit to sue Findlay for libel.

(There is a playground mantra that "Sticks and stones may break my bones / But words can never hurt me" – certainly not true in Saner's case, but I'd infinitely prefer not to suffer physical injury – I endured over half a lifetime of maternal disparagement with self-esteem intact!)

But suddenly Findlay found that proprietorial support had been abruptly withdrawn. Unlike the butterfly that stamped, he had no support from those in high places.

The Hull Packet, Mon 12 Apr 1880

second editorial

by Charles Farquharson Findlay

"The quality of mercy is not strained," according to those youthful indoctrinations which we used to receive at second-hands [sic] from one Mr. WILLIAM SHAKESPEARE, who, if not exactly a fine old English gentleman, in the society sense was at least one of the olden time. Mr. SHAKESPEARE, although cynically alleged to have been a unit of the common people, did pursue, even in his quest of poaching, some uniform principles of freebooting. We are afraid that in Hull there has just descended such a trespassing upon public opinion, by our own Tory Government, as must make every man who has a head to call his own hang it down and blush. An expiring Ministry – which mean the pliant STANLEY, worked by the persuasive Dr. ROLLIT – has just granted Mr. (Lieutenant-Colonel) SANER the retention of his Volunteer rank. Remembering the sneaking insubordination, the gross unsoldierly conduct, the behind-the-back wheedling of which this precious thing in volunteers was guilty, one might well stand back on this occasion and raise one's hands to to tune of "God a' Mercy!" If duplicity, if double under-handed dealing, if bearing false witness against one's neighbour is to succeed, then certainly let Mr, Lieut.-Col. SANER retain his rank. Make him a Peer for the matter of that; and he might as well be a Duke as a Baron. That he is barren of that old-world genuine honour which constitutes a true soldier and a gentleman may possibly be an open question – among his own personal friends. There are others, however, who will possess no doubt about the matter. A pretty farce this is indeed – if an ambitious thing dressed up in artillery clothes is to charge his Colonel Commandant with all sorts of despicable delinquencies which are, upon investigation, proved to be utterly fictitious. And if, after all this loose-witnessing, which draws a lot of foolish flies into the parlour of disgrace and of dishonour, the old spider is to turn round and whistle triumphantly that they are enmeshed, but that still he is Lieutenant-Colonel SPIDER – pray what further can be said? The whole thing is a farce, and to discuss it is a farce. Speaking for ourselves, we used to believe – a very ancient belief, no doubt – that in order to retain his rank an officer required to have the recommendation of his Colonel-Commandant. We may be mistaken; but we have not yet heard that Mr. Lieutenant-Colonel SANER has received the necessary recommendation in question from his superior officer. When he has done so, and when he has risen – which we believe, in his case, to be impossible – to a true perception of what a soldier's first duty is, then shall we believe he is entitled to this retention of his rank. At present, one cannot help reflecting what a fine example he is to his corps. The whole principle of volunteering is based upon the idea of military discipline – of order and of sub-order. Yet here we have a contumaciously contemptible endeavour to have the authority of an entire ...

... Brigade over-turned, the result of which is a mandate from the War Office, that all these disloyal and unworthy officers shall at once resign. It was indeed a matter of cashier. Those who accepted the dismissal, with what good grace they could, no doubt now feel ashamed of themselves now that they should have been, mayhap unwittingly, drawn into so disgraceful a cabal. Not so the ring-leader. With that unblushing effrontery which so well becomes him, he has brazened it out to the last. And what a last it is! If honour and equity and bravery are to come to this, that you can go and stab your commanding officer in the back, be ordered to resign, yet retain your honorary rank, and describe yourself on your calling cards as a Lieutenant of Her Majesty's Service, then all we have got to say is this, that glory is easily, cheaply, and sometimes not very worthily won. There are a few things also, that we should like to know. We should like to know if this scandal is to go unchallenged by Mr. NORWOOD or Mr. WILSON in the House of Commons? We should like to know if all those other officers who were cashiered are to be reinstated with an equal honour to that vouchsafed to Mr. SANER? And we should like, above all, to know, what volunteering or soldiering – or (for the matter of that) discipline in every matter of each day's business is coming to – if we are to be granted the privilege of coining falsehood against this one and the other without being able to substantiate the case – smirking the while, and retaining what we are pleased to think our honour, perhaps even deigning to sit on the Bench as a J.P., and writing ourselves as a Lieutenant-Colonel on our calling cards? Beside all this, Chairman of the Dock Board is a small consideration; and a single transaction in timber must be accounted a mere bagatelle – Lieutenant-Colonel SANER retains his rank; and Mr HORSLEY lives at Cottingham.

The 1880 General Election was in progress during much of March and April that year, the result not being known until 21 April, about a week after Findlay's fateful editorial. The (Conservative) Disraeli administration thereby came to an end and the (Liberal) administration of Gladstone began on 23 April.

The three-year tenure of Sir Frederick Stanley (16th Earl of Derby) as Secretary of State for War from April 1878 also terminated. The new incumbent, reluctant to accept the job, was Hugh Childers.

The "persuasive Dr Rollit" was at that time neither Sir, Dr nor MP, but a humble local solicitor - peculiar prescience on the part of Findlay.

The rather curious final sentence referred to J H Horsley, a prosperous timber merchant of that time, who local feeling suspected to have been dishonourably involved in the Saner scandal. He had recently moved away from the grimy town, to the leafy lanes of Cottingham, where he now resided at Southfield House, Thwaite Street (next to Thwaite Hall).

Questions in The House

The issue of Lieut Col Saner's dismissal, its subsequent retraction and the consequent repercussions upon the morale of the 4th East Riding of Yorkshire Artillery Volunteer Corps was twice debated1, 2 in the House of Commons. Some incisive questions were raised by the MP's for Hull, broadly in line with what we know (with the benefit of hindsight) to be the true facts of the situation, and answered by the new Secretary of State for War, who was much more concerned with defending – at considerable length and with impressive opacity - the volte-face performed by his predecessor as regards the maligned Humphrey and the malignant Saner.

Interestingly, there was absolutely no reference to the libel action then still in full swing against Findlay. Perhaps that was sub judice.

Please see the annotated transcriptions linked below – bearing in mind that Humphrey had been fully vindicated by a military inquiry several months previously, prior to the obfuscations of Rollit which mysteriously dragged down Humphrey – and Findlay, who had championed Humphrey's cause from the very beginning.

If anybody, it was Saner who should have been sued for libel (or malicious falsehood) by Humphrey, but it was clear which way the political wind was blowing and Humphrey must have decided simply to call it a day without risking the incurral of huge legal fees.

It has suddenly occurred to me that there might be certain parallels with the Dreyfus Affair which similarly involved a complicated miscarriage of military and civil justice, and the stench of societal decay – the hounding of Oscar Wilde almost two decades later might also come to mind. To the best of my knowledge, neither Humphrey nor Findlay were Jewish or homosexual, but that's beside the point. As my father used to say, parodying the typical managerial or bureaucratic approach, "My mind is made up, don't confuse me with facts".

I'm trying very hard not to declaim "J'accuse!" – after all, who was Jack Hughes anyway?

Please see below for a chronological table of Hansard's coverage of the parliamentary debates in the House of Commons regarding the deteriorating morale of the Fourth East York Volunteer Artillery Corps and its seemingly irreversible decline into chaos.

| 1) Mon 21 Jun 1880 | First Debate |

| 2) Thu 8 Jul 1880 | Second Debate |

Trials and Tribulation

Please see below for a chronological table of the Hull Packet's coverage of the remorseless legal trap in which Findlay found himself ...

| 1) Tue 20 Apr 1880 | Mr Saner & The Hull Packet |

| 2) Fri 7 May 1880 | Saner v Findlay and three Directors |

| 3) Fri 30 Jul 1880 | Queen v Findlay |

| 4) Fri 19 Nov 1880 | Findlay: Judgement and Sentence |

Breaking a Butterfly upon the Wheel

Who Breaks A Butterfly On The Wheel? was the title of a famous editorial on 1 Jul 1967 by William Rees-Mogg, editor of The Times (and father of Jacob Rees-Mogg, invariably tweed-clad MP for the Nineteenth Century) following the trial and conviction of "Rolling Stones" Mick Jagger and Keith Richards for amphetamine and cannabis offences. They were sentenced to 12 months and 3 months respectively, the severity of which led to widespread public unease.

This was a slight misquotation from a poem by Alexander Pope, and reflects an ancient form of torture or punishment, as symbolised by the image below.

Death, the Soul and Fortune

Mosaic from Pompeii (30 BC – 14 AD)

National Archaeological Museum, Naples

This depicts death (the skull) below which are

a butterfly (the soul) and a wheel (fortune).

And I think it particularly germane to the prison sentence inflicted upon Charles Farquharson Findlay at the end of his trial back in 1880. He was also fined £50, of course, a not inconsiderable sum in those days, but that was readily met by his friends and supporters.

The term in prison led to his death, however, and the break-up of his family, all for a mocking editorial commenting scathingly on the vulgar pretensions of a man already widely despised by the people of that area.

Although those in the entertainment industry generally say there's no such thing as bad publicity, those in engaged in the making or the administration of repressive legislation customarily dislike the Fourth Estate on principle. Indeed Stanley Baldwin said of the press barons Rothermere and Beaverbrook that they exercised power without responsibility, the prerogative of the harlot throughout the ages.

However, that too was a quotation, from Kipling.

Baldwin's son Oliver recounted the story in 1971, in an address to members of the Kipling Society (hyperlink now broken):

"As told me by my father ... Kipling was attracted by the charm and enthusiasm of a rich young Canadian imperialist whose name was Max Aitken,§ later to become Lord Beaverbrook. They became friends. When Aitken acquired the Daily Express his political views seemed to Kipling to become more and more inconsistent, and one day Kipling asked him what he was really up to. Aitken is supposed to have replied: 'What I want is power. Kiss 'em one day and kick 'em the next' and so on. 'I see', said Kipling, 'Power without responsibility – the prerogative of the harlot throughout the ages.' So, many years later, when [Stanley] Baldwin deemed it necessary to deal sharply with such lords of the press, he obtained leave of his cousin to borrow that telling phrase."

§ Oddly enough, Granny Kaulback was well-acquainted with the ambitious young Aitken when he was a protégé of her uncle, John Fitzwilliam Stairs.

But Findlay had no truck with power for himself – he was simply a highly-principled young idealist who was appalled by the misuse of power and privilege. But ultimately it broke him, and he died.

Durance Vile

During Findlay's six-month sojourn in the grim-looking Holloway Castle prison, he was rather quaintly categorised as a First Class Demeanant, or simply First Division prisoner, in contrast to the Second or Third Divisions of prisoners. This classification seems to have been established in the 1865 Prison Act, and was continued in the 1898 Act of that name (as per the excerpt below from Winston Leonard Spencer-Churchill: Penal Reformer, by Alan S. Baxendale, publ Peter Lang, Oxford 2010)

Findlay's own experience in the First Division did not, however, live up to this high ideal, as we can read below from a memoir 1, 2 published after his death by a friend, evidently of long standing, who visited him there.

I'm most grateful to William Gueritz for this totally unsuspected published account of Findlay's incarceration.

A JOURNALIST IN GAOL.

THE subject of imprisonment for libel is just now occupying the minds of those who are connected with, or take an interest in [it], and indeed those who read papers so it may not be out of place to narrate what in the present day constitutes the treatment of a "first-class misdemeanant" placed in durance vile through the indiscretion of the pen or inadvertence in editing. The fairy tales of the past, in which the happy literary martyr is represented sitting luxuriously in a well-appointed "cell," with books, papers, pipes, and other comforts, are not so well defined if one has the misfortune to have a friend inside the walls of "Holloway Castle" to visit under circumstances of first-class incarceration. I can only speak from the experience of visiting the editor of an important provincial paper who, a few years ago, perpetrated a libel upon the colonel of a volunteer. Regiment, the libel consisting entirely in facts received from some of the officers of the corps. For this he received six months, as a first-class misdemeanant, and a fine of £50 sterling. I went to Holloway Gaol to visit him. Well do I remember the feeling of surprise at the query made by the janitor as to whether I had concealed for my friend's benefit any ardent spirits or tobacco, and the gentle patting of my costume, which ended in the annexation of my cigarette-case. I was then handed to a smart warder, whom I afterwards learned was known as "Cupid"—why, heaven only knows! We crossed a dreary-looking space—the recreation ground—and came to a door, next which a barred window revealed within a group of gruesome and woe-begone faces peering into the open, probably watching for friends, it being a visiting day. Inside the door we found ourselves at the foot of a stone staircase. Here Cupid paused and clapped his hands together three times, in response to which appeared a tall and appropriately surly-looking warder, who seemed to be making unnecessarily loud music with a bunch of keys. My friend's name was shouted up to him by my chaperon, and he beckoned me to come up. The new guide ushered me into "the visiting room." My fond visions of the place were soon scattered.

Sufficient to say the floor was concrete, the tables and benches of unsympathetic deal. Nor shall I ever forget the apparition of my woe-begone friend coming in at the door clad in his ulster coat — for warmth, he told me. What a change the month which had already passed of his "first-class misdemeanancy" had wrought upon his stalwart Scotch frame! Pale and worn, I scarcely knew him. He smiled a sickly smile, and motioned me to take a seat. Then followed a tale of his sufferings. "The worst of all," said he, "is the want of sleep: as you know I have been all my life accustomed to late hours, and now they lock me up at eight and turn out the light at half-past. It is dreadful." After some inquiries as to whether he was allowed to read and pursue his avocations, he replied with a bitter laugh, "Do I look as if I could work - and if I did the chaplain must read and approve of my stuff, and he is an awful editor!" "You get the papers we send you?" was the next query. "Not all, I am afraid; the chaplain deals with that department also." It may here be mentioned that, with bitter and cruel irony, when he was emancipated the officials handed him a great heap of papers, chiefly consisting of the World, Truth, Punch, and the Sporting Times, which the holy man in office had considered of too secular or dangerous a nature to be admissible. "We exercise and mix with all sorts and conditions of men, and for the consideration of three shillings a week I am permitted the luxury of employing a more needy prisoner than myself to clean out my cell and do things of that sort." "Some of the prisoners," he went on, "take very different views of their fate. Look at that poor devil with his face on the table; he is a hopeless debtor. His wife was here yesterday, and he has been crying ever since. Now this is his solicitor, and I suppose he will have to be paid somehow. I will show you quite a different class of character. You must see him," and he led me into the corridor and pointed out a cheery-looking youth of sporting cut. "He is a bookmaker who has purposely got himself locked up during the frosty season—as he naïvely puts it, to 'Save expenses and get the whisky out of his skin.' The ruling passion is still strong upon him, and even here he manages to get a little semblance of sport. He has managed with the cunning of his craft to conceal a number of sovereigns in some way or other, and when opportunity permits he lends portions of them to some poor wretch or other, and "flies him for thick 'uns," as he terms it. When the gambling is over he collects his bullion, and rewards his opponent with some hope of future refreshment. Another great trial is chapel; it's not so awful as the long, dark nights, but it is very bad. And on Christmas Day it was most pathetic to see the faces of the congregation while that good man the clergyman reminded them that upon that holy and happy festival they might have been in the bosoms of their families but for their own misdemeanours." Time was up, and having secreted some documents he was anxious to have delivered without the moral supervision of the authorities, I bade my friend adieu, and having regained my cigarette-case, left the gate, with its glaring stone dragons on either side, a sadder and a wiser man. The subject of this sketch was liberated at the expiration of his term, but not till the fine of £50 was paid by a subscription raised among his fellow-workers of Fleet Street. He afterwards was appointed editor of a paper which took him to the more genial climate of the South Coast. The trials of a first-class demeanant had not only entered into his soul but into his lungs, and he succumbed to a consumption [tuberculosis], leaving a young wife, and an infant which was born during his incarceration.

As far as I know, I've only ever been closely acquainted with three involuntary guests of HMP system – a jactitator of marriage, an armed Post Office robber, and a solicitor who naïvely invested his client's funds in the winning potential of three-legged race-horses. But I've lived a sheltered life.

Epilogue

His term of employment, his last, with the Dover Chronicle evidently coincided with the birth of his younger daughter Hannah for whom the UK 1901 census records Dover as her birthplace on 3 Jun 1882. The obituary reproduced above certainly mentions his widow as still being part of his household.

For details of the children's subsequent care please click Jessie Smith Findlay.

A very intriguing eulogy of a person unknown, by somebody of the initials JSM, has recently surfaced, and I rather think it was addressed, posthumously of course, to Charles Farquharson Findlay.

References to his personality and appearance, and the "varied skies of [his] arduous prime", are entirely consistent with Charles Farquharson Findlay the man. As is his relationship of full cousin to John Ritchie Findlay, proprietor of The Scotsman and patron of the arts (their shared grandfather was Peter Findlay (1777 – 1855)).

So who might the JSM have been? Presumably a contemporary, and from the same part of Scotland – Angus, even Arbroath – in their youth. Should be easy, but I haven't yet worked it out.

But it's still further evidence of the great respect and affection in which C F Findlay was held by his contemporaries.

Tributes

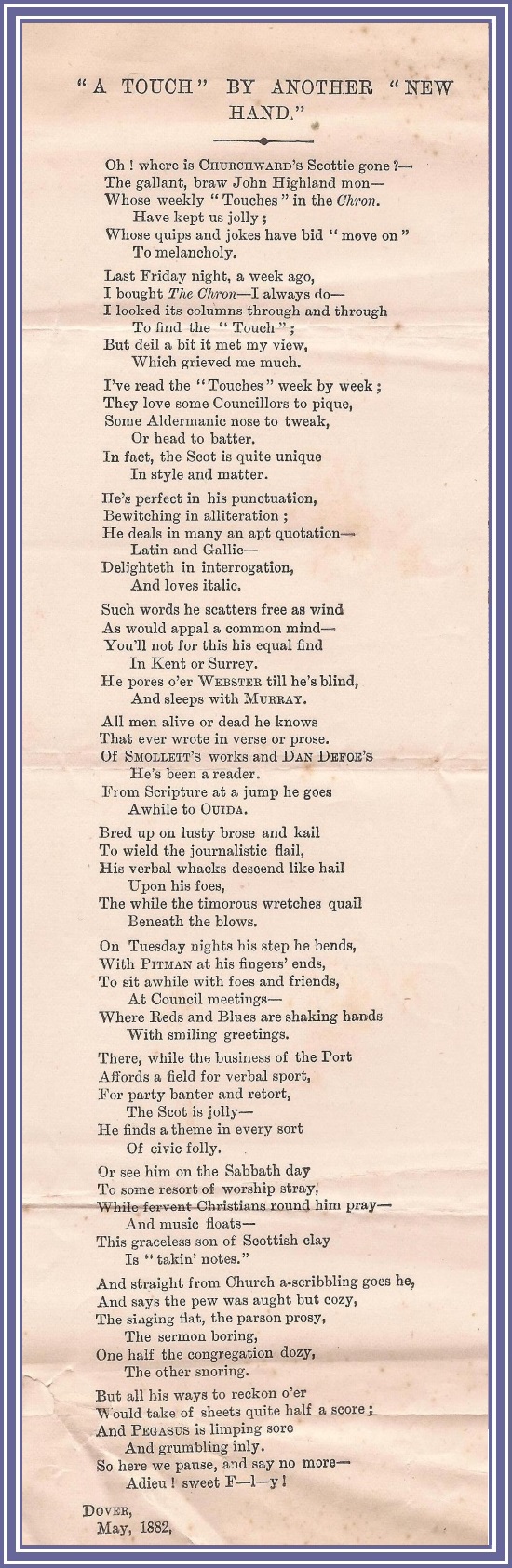

This rather wonderful poetic accolade was evidently composed at about the time when Findlay relinquished his editorship of the Dover Chronicle, a month or so before the birth of his younger daughter Jessie Frances Hannah Findlay, my grandmother.

She was in fact born in Dover, but at some point onward in the year the family removed to Torquay, where the climate was thought to be healthier, or at least remedial. There's no indication that he embarked on any further journalistic employment, and so this vibrant account of his editorial column "Touches" can be regarded as his epitaph.

There's absolutely no clue as to who it was that wrote this sprightly encomium (though evidently a reader rather than a fellow-journalist), and whether it was published by the Dover Chronicle or privately circulated.

The capitalised allusions (Churchward, Webster, Murray, Pegasus) ring no bells with me, and the authors mentioned (Tobias Smollett, Daniel Defoe and Ouida), though recognisable, cut no particular mustard any longer. Pitman(s), that is, the form of short-hand invented by Sir Isaac Pitman, however, is still in active commercial use, though, I suppose, has lost ground to stenography and speech-recognition software. Findlay was evidently acclaimed as a virtuoso with pencil and reporter's notebook!

But, overwhemingly, we recognise throughout this tribute all the intellectual qualities and crusading zeal of the Findlay we first encountered in the pages of the Hull Packet during his confrontations with corruption, connivance and complacency.

His health may have been broken but his spirit had not been crushed.

This next accolade is posthumous, and though it touches upon his journalistic career it seems to concentrate on his dramatic talents (I would say 'thespian', but that has a suggestion of the sexually indeterminate, and Findlay's eigenvalue was definitely masculine).

That said, there always seems to me to be an essential common factor to journalism, acting, politics, the Bar, and perhaps other professions too (estate agency, maybe!), in that they are all performance arts, that is to say, based on pretence, persuasion and projection of personality, and always teetering on the edge of a precipice; although the Bar does undeniably require a serious underpinning of academic study and intellect, its practice is pure showmanship.

There I go again, but here anyway is the deeply appreciative (though anonymous) tribute to Findlay that I mentioned. It was published in the Irvine and Fullarton Times, p4 Col 2, on Fri 12 Oct 1883 (click here, courtesy of Andrew Gueritz).

The "brilliant, graceful and bewitching" Rose Massey who also took the audience by storm that Saturday afternoon at the Glasgow Gaiety theatre, was like Findlay a moth to the flame.

For a fascinating account of the genesis of The Two Roses, see Henry Irving and the Victorian Theatre, by Madeleine Bingham, publ Routledge, Jul 2015 (Chapter 5, "Wedding Bells and Sleigh Bells").This quotation does indeed feature in the Molesworth canon, though even the inky Nigel himself would have been hard-pressed to quote the full exclamation:

"Eheu fugaces Postume, Postume, Labuntur anni, nec pietas moram Rugis et instanti senectæ Afferet, indomitæ que morti."

"Postumus, Postumus, the years glide by us: Alas! no piety delays the wrinkles, nor the indomitable hand of Death."

Horace, Carmina, Book II. 14. 1.Charles Findlay's Poetry

I'm enormously grateful to my cousin James Waddell, justly renowned for his infinite-resource-and-sagacity, who has conjured up a document of such unexpected and indeed unsuspected origin, that I was (temporarily) quite lost for words and stared at his emailed attachment with dropped jaw and popping eyes.

The love-poems of Chas Farquharson Findlay may not prove to be a literary sensation, but for those few who remember his name and the all-too-scanty details of his life, these three poems will come as a revelation.

It's got to be said that they are all rather downbeat, and suffused with the sense of irretrievable temps perdu, and unfulfillable longing for his lost love.

I just read somewhere that Eliot's The Lovesong of J Alfred Prufrock (written some 50 years later) has been described as "a small, dark mope-fest of a poem", and so I hastened to check it for any similarities or resonances by means of which CFF's own mope-fests could be calibrated. Resemblance was there none (though lots of outstanding images that linger in the memory), so I'm no better enabled to provide a helpful commentary.

English Lit passed me by at school, particularly the analytic deconstruction of poetic meaning and allusion, and so my preference is for uncomplicated epic narrative (Macaulay's Armada, Byron's Sennacherib, Coleridge's Ancient Mariner, for example, particularly when arrogant might is humbled!).

In particular, I entirely missed out on the technical stuff about verses versus stanzas, feet, metre, rhythm, rhyming schemes and on. Occasionally I do google these things, but it always seems that one obscurity is explained in terms of another obscurity (just as in the basics of musical theory that I forlornly tackle from time to time).

However, I was initially encouraged by the ABABCDDC rhyming scheme of the opening verses of Poem #1, that CFF had been inspired by another mope-fest, Tennyson's Mariana [of the Moated Grange], published just over a decade previously. But CFF's schema all too soon evolved, and the lengths of his (verses? stanzas?) started to fluctuate. And the luckless Mariana's perceived problems were quite the reverse of his, anyway – if only she'd put her picture in an up-market lonely-hearts column, it would have solved things almost immediately.

There is a similar pattern in Poem #2, where the opening rhyming scheme of ABABCCA, though it does prevail for much longer, eventually falters and mere anarchy is loosed upon the work.

Perhaps these inconsistencies result from additions and redactions over a period of several years – or perhaps he simply wrote as his muse dictated, scornful of foolish consistency, that hobgoblin of little minds.

Poem #1

The opening declamations ("I have loved once", "O headstrong boy", etc), the absence of any date, the narrative style, suggest to me (well-known expert on romantic poetry that I am) that this is the first of the three poems. Add to that its up-front position in the manuscript, and I feel even more confident.

That established, it's not too difficult to work out the chronology from the heading to #2, which establishes that either the romance itself, or the ensuing composition of #1, took place in 1865. At which time he was just 12 years old, or else we've got his date of birth badly wrong (which is just possible). His emotional precocity was well ahead of even Robert Burns, and one might wonder whether such literary influence infused both his emotions and his subsequent verse.

But we can probably all remember intensely passionate feelings of this kind at that sort of age, and it wouldn't do to dismiss CFF's experience as a mere crush or infatuation. And whatever the literary critic may say about the verse, and its sometimes over-florid style or structure, it's not a bad effort, so read on (or click here for a pdf version, or here for a transcribed version).

Poem #2

I've already more or less exhausted my powers of critique, and so after paying respectful attention to the map (which suggests, probably rightly, that the scenery and seascape of the Firth of Solway were pretty conducive to poetic inspiration), let's read on (or click here for a pdf version, or here for a transcribed version).

One of my wife's favourite words is thole, of Scots or North Country origin, often encountered in Georgette Heyer's Regency romances, meaning to put up with stoically, or endure. One might well conjecture that after the celebrated exchange between the Earl of Uxbridge and the Iron Duke at the Battle of Waterloo, Lord Uxbridge's sotto voce as he was helped on to the stretcher, was a slightly less quotable "Well, you win some, you lose some, I'll just have to thole it".

More or less synonymous, and also of Scots origin, is dree, generally met with in the context of dreeing ones weird, where weird is defined as fate or destiny (not themselves entirely equivalent, but never mind). The point I'm coming round to, ever so slowly, is that GFF – on the evidence of these poems anyway, certainly at the age he was then – wasn't one to thole his misfortunes or dree his weird. He was still very youthful and disappointments then are harder to cope with than in later life when of course they have become routine. For him, of course, a very tough time indeed was lying in wait, which would need all the endurance he could muster.

Poem #3

CFF's possession of, or at least access to, a typewriter indicates that this is the last of the three newly-discovered poems. Only the fourth verse reveals that he is still sorrowful, yet allowing that hope and happiness are still in prospect, though presumably with a new inamorata.

Barrochan seems to be an area a few miles south-west of the Glaswegian suburb of Paisley. The local girls are its other claim to fame, as evidenced by the rollicking ballad of Barrochan Jean.

Now rising 24, already a successful journalist on The Glasgow News and soon to become editor of the Hull newspaper that was to bring such woe, his style is much simpler, plainer, even starker. He has moved on from the hang-ups and entanglement of the earlier poems, though still perhaps prey to the occasional "if only ..." or "had I but ..." that come to us all.