The Bryce Family and Garinish / Ilnacullin

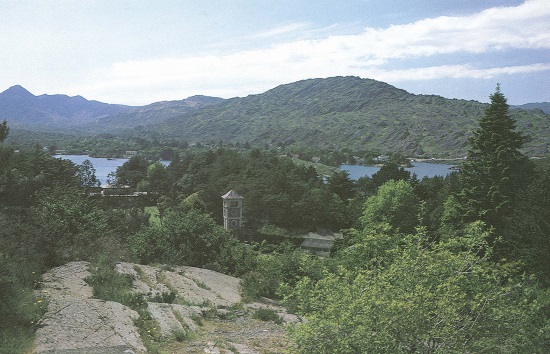

View across Ilnacullin (note the Clock Tower) towards Sugarloaf Mountain to the SW

Unlike the Hutchins and the White families, the Bryce family came to Bantry, or more properly Glengarriff, in relatively recent times, and indeed their connection with the area lasted but two generations. But their legacy, of the inspirational transformation of the island of Garinish, or Ilnacullin (sometimes Illnacullin) as it is now more officially called, is world-renowned.

John Annan Bryce (1844 – 1923/4) and his wife Violet (1863 – 1939) bought the 37 acre (15 hectare) island from the British War Office in 1910. A well-educated man of Scottish extraction, he had been a successful businessman 'out East' and was Liberal MP for Inverness Burghs from 1906 to 1918, when the constituency was abolished. She was English, of good family, and very interested in gardening. Their younger son Nigel had just died, aged only 17, and so they evidently decided to choose a new focus in their personal life, by an extraordinarily creative make-over of the whole island.

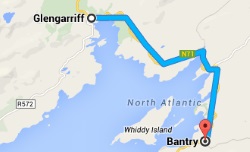

The name Garinish means 'near island' in Irish (gar = near, inis = island), and indeed it is located just offshore of the village of Glengarriff. The village itself is some 12 miles from Bantry, round the end of Bantry Bay, at the top of the Beara peninsula. There is also a much smaller island of Garinish West a few miles further down the coast, within a stone's throw of Zetland jetty.

But Violet preferred the name Ilnnacullin, meaning 'island of holly' in Irish (oileán = island, chulinn = holly), and this is the name used by the National Parks and Monuments Service (to whom the island now belongs) to differentiate it from Garinish Island in Co Kerry.

The British authorities had built a Martello Tower at the highest point of the island, complete with cannon mounted on a circular iron track, to counter the perceived threat from the French, following the unsuccessful French Invasion of 1796 instigated by Wolfe Tone.

The Bryces were convinced that with its sheltered situation and the warming influence of the Gulf Stream, a wide range of oriental and southern hemisphere plants could flourish in the almost subtropical climate of Glengarriff. Keenly interested in horticulture and architecture, they planned to build a mansion and lay out an extensive garden on the island. They commissioned the eminent English architect, and landscape garden planner Harold Ainsworth Peto (1854 –1933), to design these (coincidentally from my point of view, he had some years previously redesigned West Dean House on behalf of Willie James).

Very few people these days realise the truly epic scale of what was intended – I myself certainly hadn't, until reading two excellent recent accounts.1, 2

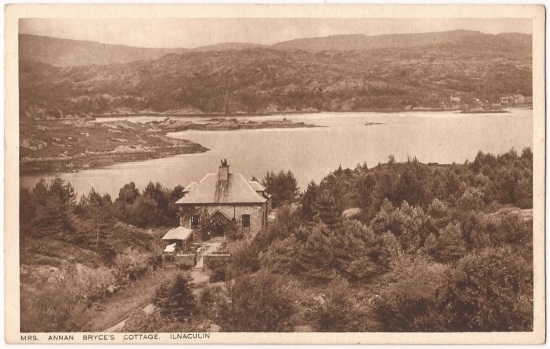

Plans for a seven-storey mansion were prepared incorporating the Martello Tower, but it was never built. Instead an extensive cottage, always known as Mrs Bryce's Cottage, became the home of the Bryce family.

Among their guests were the dramatist and self-publicist George Bernard Shaw, who stayed on the island in 1923 while writing his play Saint Joan, and the poet Æ (George Russell).

There is a persistent myth (which I innocently believed until recently encountering the link following) that the island had thitherto been barren and uninhabited, and that a vast quantity of soil had to be transported from the mainland before the project could proceed.

garinishisland.wordpress.com/2011/11/04/the-soil-on-garnish-island/

It is thought that the Bryces brought over tons of topsoil from the mainland, but this is only speculation, as there was a 'quarry for soil' marked on Harold Peto's map of Garinish Island. American writer Harold Speakman (1888-1928) describes his encounter with Violet Bryce in Here's Ireland (1925):

The lady greeted me cordially. "I hope", she said, as we went up a path made rich by the scent of early roses, "I hope that you haven't heard the ridiculous story about our bringing boatloads of earth here from the mainland!" "Millions of boatloads…", I quoted.

"Now where could you have heard that!" she demanded with some warmth. "I never knew anything so stupid!" "It was an old woman coming over the hill", I said. "But it doesn't seem so bad to me. If a place were barren and one wanted to live here, why shouldn't soil be brought from anywhere?"

She looked at me imperiously and a little scornfully. Evidently this was a subject of long standing and some delicacy.

"In the first place, there isn't land on the mainland to take away; in the second, the thing is too silly. I can't imagine any one doing a thing like that – except perhaps an American millionaire!"

"Whew! This isn't beginning very well", I thought. But in another moment she had forgotten her annoyance and was showing me a path so completely carpeted with fallen pink blossoms that in places it was entirely hidden from sight.

However it took years to enrich the existing thin peaty soils which were mainly Murdo Mackenzie's achievement as he was known to collect leaves and other natural debris from the mainland to enrich his compost heap. In the Irish Times from 13 Feb 1931 the issue was described as follows:

The greatest compliment paid to Mrs. Bryce is the legend that all the soil for the garden had to be imported: some say from the mainland, and some say from England. This of course is quite incorrect, the fertility of the island being due to its own soil and climate, together with a great deal of well applied industry. In fact there is no reason why the mainland should not yield the same results if properly cultivated, and the possibility of fruit-farming in the district is one that could well be investigated.

I should say here and now that the blogger lestrange, with whom (I believe) I'm personally acquainted, is, unarguably, by far the most knowledgeable authority on almost all matters covered in this Connection. And this extract so very neatly undermines all previous received wisdom.

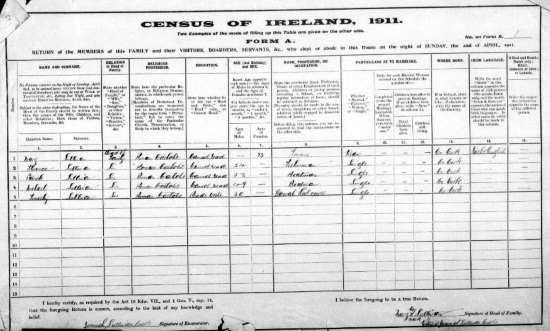

As does lestrange's further observation that Garinish was in fact inhabited at the time of the Bryce's purchase, and for at least a year or so afterwards, as is shown by the Census form for 1911:

We see that Mary Sullivan, a widow of 73, was described as a farmer – implying that at least some of Garinish was fertile enough for family self-sufficiency. Her four sons – Florence (54, fisherman), Patrick (52, boatman), Michael (49, boatman) and Timothy (30, labourer) – were all single, not altogether surprisingly, as men in rural Ireland right up to a generation ago adhered to the age-old tradition of waiting until they were economically independent (by inheriting the family farm or fishing boat, for example) before entering into marriage – their wives might well be 20 or 30 years younger than them.

(There are other interesting features to note – Mary was bilingual in Irish and English, though her sons spoke only English; all were illiterate save the youngest son Timothy; and the 19 year gap between Michael and Timothy suggests intervening daughters who had got married, or literate sons who had escaped the poverty trap by emigrating to England or America).

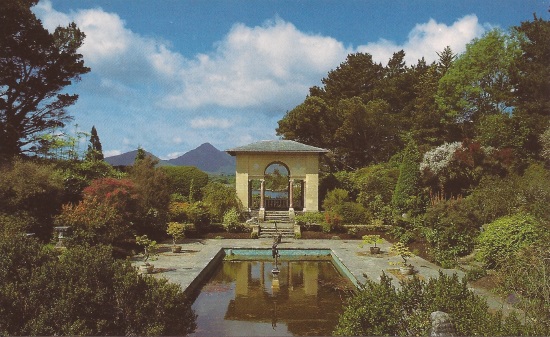

Whatever may have eventuated for the Sullivans, more than 100 men were engaged between 1911 and 1914 in moving soil, blasting rocks, planting trees, laying paths, as well as building a walled garden, a tall clock tower and a wonderful Italianate garden complete with casita, pool and pavilion.

Italianate Garden, with Sugarloaf (Gabhal Mhór) visible to the LH side of the pavilion

I get the impression that the outbreak of the First World War, and the general wretchedness of the war years, put a stop to any progress with the transformation. And the Easter Rising in 1916, leading to the Anglo-Irish War of the early postwar years, all of which led to savage reprisals by the British authorities, had a most incongruous impact on the Bryces, as will be recounted later. Their persecution by the Auxiliaries (ADRIC's) must have cast a dark shadow over Annan Bryce's last years.

Worst of all, his finances had been ruined by the effects of the 1917 Bolshevik revolution on his investments in Russia, which had been rendered worthless. He was no longer a rich man. The immense scale of the envisioned landscaping was drastically curtailed and the envisioned seven-storey mansion was abandoned.

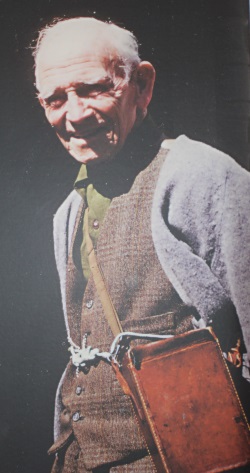

Annan and Violet Bryce, with friends, on the steps of the casita facing the pool

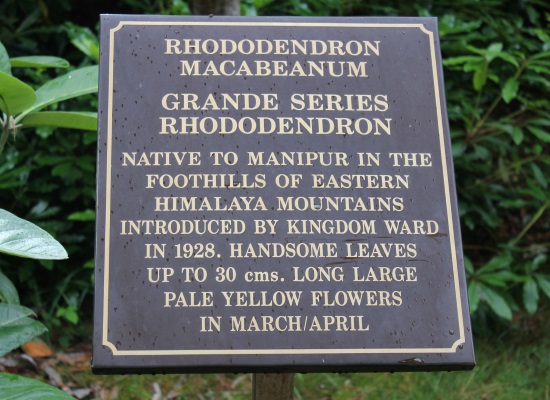

After the death of Annan Bryce in 1923/4, the development of the gardens was continued by his widow, Violet. But strong winds had damaged much of the early planting. Fortunately, she was ably assisted from 1928 onwards by Murdo Mackenzie (1896 – 1983), an outstanding young Scottish gardener who was put in operational charge of the garden and successfully established shelter belts, of mostly Scots and Monterey pine, as a result of which it became possible to implement a modest but resilient fraction of Peto's designs for the distinctive gardens of present-day Garinish / Ilnacullin, and to initiate the splendid collection of rare and tender plants for which the island is now famous.

In 1932, Violet's son Roland Bryce (1889 – 1953) took her place, continuing to add interesting plants from many parts of the world. On his death in 1953, the island was bequeathed to the Irish people and entrusted to the care of the Commissioners of Public Works. Murdo Mackenzie remained in charge of the garden when it passed into public ownership until his retirement in 1971. For a wealth of fascinating detail, beautifully presented, about every aspect – historical and horticultural and much else - of the Bryces' achievements on Garinish, please consult lestrange's website.

I understand (Aug 2017) from the O'Sullivan family of Glengarriff that Mackenzie was succeeded as head gardener by Michael G O'Sullivan, a cousin of Maggie O'Sullivan. And it is said (see below) that, a decade later, Michael was succeeded by his son Finbarr O'Sullivan, who was head gardener through the next three decades.

I also learn (see below) that Finbarr O'Sullivan is now overseer of the gardens, with Bernard O'Leary as head gardener.

www.schwarzaufweiss.de/Irland/garinish_island.htm

"With Finbarr over the island

While visitors usually proceed around the island according to their own inclinations and at their own pace, we have an appointment with Finbarr O'Sullivan, who has been taking care of Ilnacullins' gardening for three decades, just as his father had done before."

image.isu.pub/160701172251-48966a1fbd98f626f98bab73cfedd059/jpg/page_39.jpg

Heritage Ireland, Issue 4, Summer 2016

"The island's dedicated and knowledgeable team of staff have been instrumental in helping to deliver the changes on the ground under the supervision of Finbarr O'Sullivan (Overseer) and Bernard O'Leary (Head Gardener)."

Apart from the information readily available from the family gravestones in Bantry's Abbey Cemetery, I've been heavily reliant on the following websites for details of the Bryce family history tabulated below:

Several dates and names have also been corrected by means of the following fascinating booklet recently (Aug 2017) presented to me during a flying visit to Mrs Bryce's House on Ilnacullin.

- Ilnacullin: The Bryce Legacy; Karol Mullaney-Dignam, The Office of Public Works, Ireland 2015

| # | Individual | Spouse / Partner | Family |

| 1 | Alexander Bryce (d ca 1729) |

John Bryce (b 1738) | |

| |||

| 2 | John Bryce (b 1738) |

Robina Allen | James Bryce (1767 – 1857) |

| |||

| 3 | Rev James Bryce1, 2 (1767 – 1857) born in Airdrie removed to Killaig, near Londonderry in 1805, as anti-burger Secession Minister founder of the Associate Presbytery of Ireland |

Catherine Annan | ancestry.co.uk give

Rev Dr Reuben John Bryce MA LLD (Principal of Belfast Academy) (1802 – 30 May 1888) Robert Bryce MD (b 1804) James Bryce LLD (19 Oct 1806 – 23 Jul 1877) William Bryce MD (b 1808) David Bryce (Accountant) (b 1809) Archibald Hamilton Bryce (b 1811) Robina Bryce (b 1814) (m James Clark, farmer, Coleraine) |

| |||

| 4 | James Bryce1, 2 LLD, FSG (19 Oct 1806 – 23 Jul 1877) Head of Glasgow High School |

Margaret Young (ca 1813 – 18 Aug 1903) (m 1836) |

Mary Bryce

Katharine Bryce James Bryce (10 May 1838 – 22 Jan 1922 John Annan Bryce (1844 – 25 Jun 1923) |

| 4 | William Bryce MD (b 1808) |

Janet (?) Hastie (m 1848) |

Thomas Hastie Bryce (20 Oct 1862 – 16 May 1946) Portrait |

| 4 | Archibald Hamilton Bryce (b 1811) Head of Edinburgh High School, Rector of Edinburgh Collegiate School, author of numerous textbooks of Greek, Latin and ancient geography |

Mary Ferguson (b 1833) |

ancestry.co.uk give

George Ferguson Bryce (b 2 Jun 1855) James Annan Bryce (b 18 Jan 1857) John Robert Bryce (b 27 Nov 1858) Anne Bryce (b 16 Apr 1860) Archibald Hamilton Bryce (b 1 Nov 1862) Mary Ferguson Bryce (b 16 Jun 1865) Charles Henry Bryce (b 14 Nov 1867) |

| |||

| 5 | James Bryce1, 2, 3, 4 OM FRS MP 1st & last Viscount of Dechmount, Lanarks. (10 May 1838 – 22 Jan 1922 Portrait |

Elizabeth Marion Ashton (1854 – 27 Dec 1939) (m 23 Jul 1889) | sp |

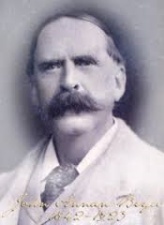

| 5 | John Annan Bryce1, 2 MP (1844 – 25 Jun 1923)  |

Violet L'Estrange (10 Oct 1863 – 3 Nov 1939) (m 2 Aug 1888)  daughter of Artillery Captain (later Major) Champagne L'Estrange (3 May 1832 – 5 Mar 1900) |

Roland L'Estrange Bryce (19 Nov 1889 – 4 Dec 1953) Margaret (Margery / Marjorie) Vincentia Bryce (1891 – 1973) Nigel Erskine Bryce (1892 – 1910) Rosalind Violet (Tiny) L'Estrange (Bryce) Tudor-Craig (1894 – 1979 |

| |||

| 6 | Roland L'Estrange Bryce (19 Nov 1889 – 4 Dec 1953) as per gravestone in Bantry cemetery |

Unmarried | |

A Troubled Time

There is a extremely perceptive introduction to Voices From The Great Houses, that explains the predicament of Anglo-Irish (mostly Protestant) families in Ireland as the nineteenth century gave way to the twentieth, and the militancy of the radicalised section (IRA activists or Sinn Féinn supporters) of the Catholic majority in the south steadily incandesced in the face of the dithering of the British House of Commons over 'Home Rule' for Ireland, and the intransigence of the Orange (extreme Protestant) majority in the north.

Civil wars are always the ugliest of conflicts, and that conducted between the British military and paramilitary forces and the IRA (who, remember, were still technically UK citizens) during the Troubles in the run-up to the establishment of the Irish Free State in 1922, was no exception. The ground rules had of course been set in concrete by the crushing of the Easter Rising in 1916 and the wholesale executions that followed.

I'm no historian, but I believe that more or less all the problems between England and her Celtic neighbours – Wales, Scotland and Ireland – can be traced back to the Normans. Saxon England was a peacable agrarian society that just wanted to shake off the Viking onslaughts. But no sooner had this been achieved (by King Harold the Second, Godwinson, the last true King of England) than the Normans (who themselves were second-generation Vikings) took us over, and gradually started to target the Welsh, the Scots and the Irish – with predictably unfortunate long-term consequences.

The polarisation of English society inflicted by 1066 and all that is still with us today, IMHO. It's more or less a fact of life that the public schools, the military and The City are a neo-Norman preserve, and the rest of us are quasi-Saxon serfs. I exaggerate of course, but not much. Whenever my ears are bent by Scottish or Irish tirades about their oppression by the English, I simply think "me too, mate, the ruling classes treated my lot just as badly".

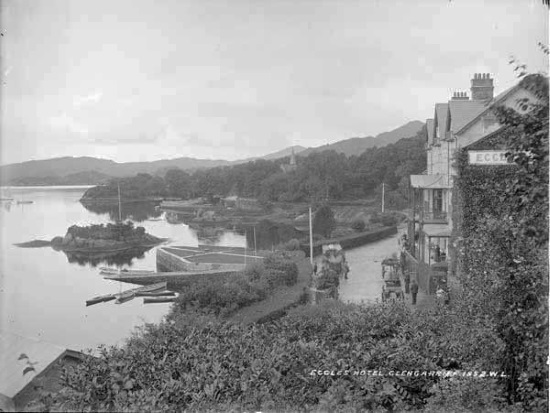

For some reason that is still hard to understand, Violet Bryce earned the enmity of the occupying British military during the troubles – it's possible that she herself was Catholic despite her husband Annan's Presbyterianism, but in any case she had in 1916 paid to have the Eccles Hotel in Glengarriff to be converted into a recovery centre (The Queen Alexandra Home of Rest for Officers) for commissioned soldiers wounded in the trenches. What was not to like?

But read on.

www.theauxiliaries.com/companies/j-coy/eccles-hotel/eccles-hotel.html (now discontinued)

John Annan Bryce was the Liberal MP for Inverness Burghs from 1906 until 1918. and was the younger brother of Lord Bryce, Chief Secretary for Ireland (Dec 1905 – Dec 1906 in the Campbell-Bannerman Liberal administration).

His wife, Violet (née L'Estrange), came from a British military family. Towards that end in 1916 she purchased the Eccles Hotel in Glengarriff and converted it into a convalescent home for officers in Ireland – the first in the country.

Their 'Establishment' credentials were impeccable, and it might have been supposed that the British military presence itself would pose no threat to them.

On 25 Sep 1920, however, John Annan Bryce wrote a letter which was was published in The Times on 30 Sep 1920.

To the Editor of The Times

On September 16, at 9.45 a.m., a lorry full of soldiers from Bantry stopped in front of the Eccles Hotel, Glengarriff, where I have been staying since August 19. The manageress went to the door and was handed by a soldier an envelope addressed in handwriting 'The Manageress, Eccles Hotel, Glengarriff.' It contained an unsigned and undated slip worded as follows:-

'In some districts loyalists and members of his Majesty's forces have received notices threatening the destruction of their houses in certain eventualities. Under these circumstances it has been decided that for each loyalist's house so destroyed the house of a republican leader will be similarly dealt with. It is naturally to be hoped that the necessity for such reprisal will not arise and therefore this warning of the punishment which will follow any destruction of loyalists' houses will be widely circulated.'

I at once sent a copy of this notice, mentioning the circumstances, to General Sir Nevil Macready, and said that, as it was contrary to his recent proclamation against reprisals, I presumed it was issued without his authority or knowledge. I received, to my surprise, the following reply:-

'Sir, – Sir Nevil Macready asks me in reply to your letter of the 16th instant to state that he is acquainted with the distribution of the notices, a copy of which you enclosed. Truly yours, William Rycroft, Major-General i/c Administration, Ireland, G.H.Q. Parkgate, Dublin, 18 September, 1920.'

On the 17th inst. I wrote a similar letter, with copy of notice to the O.C., Bantry, asking that, as on the night of August 15 the large garage of this hotel had been burned by the police who had also threatened to burn the hotel itself, he would give an assurance against further molestation. I gave him as a special reason for protection that the present proprietress had acquired the hotel in 1916 for conversion into a convalescent hospital for officers, that it was the first such hospital in Ireland, and that with the title of 'Queen Alexandra's Home of Rest for Officers,' first under the Red Cross and afterwards the Dublin Command, it had – she being commandant – housed hundreds of wounded officers, while the only return for her pains and expenditure of many thousand pounds, which both the Red Cross and the War Office refused to repay, had been the burning of the garage. To this letter I received the following Gilbertian answer:-

'To J. Annan Bryce, Esq., Eccles Hotel, Glengarriff. In reply to your letter of September 17, 1920, addressed to O.C. Barracks, Bantry. It appears that slips similar to the one to which you evidently refer are being distributed about the country. On investigation I find that an officer of my battalion picked one of them up. This officer having seen similar slips in Bantry and other places thought it would be a good thing to hand it in to one of the hotels in Glengarriff as he passed through. As yours was the most convenient, being close to the road, he put it in an envelope and addressed it to the manageress and handed it in as he passed. L.M. Jones, Lieutenant-Colonel, Commanding Troops, Bantry and commanding 1st Battalion The King's Regiment. Bantry, September 20, 1920.'

I also wrote to Sir Hamar Greenwood, but have received no reply. It will be seen that neither Sir Nevil Macready nor Colonel Jones disavows the notice, and that Colonel Jones makes no answer to the request for an assurance of non-molestation.

I may add that there is no justification for the issue of such a notice in this district, where the only damage to loyalists premises has been done by the police. In July they burned the stores of Mr. G.W. Biggs, the principal merchant in Bantry, a man highly respected, a Protestant, and a lifelong Unionist, with a damage of over £25,000, and the estate office of the late Mr. Leigh-White, also a Unionist. Subsequently, in August, the police fired into Mr. Biggs's office, while his residence has since been commandeered for police barracks. He has had to send his family to Dublin and to live himself in a hotel. Only two reasons can be assigned for the outrages on Mr. Biggs, one that he employed Sinn Feiners – he could not work his large business without them, there being no Unionist workmen in Bantry – the other a recently published statement of his protesting – on his own 40 years' experience – against Orange allegations of Catholic intolerance.

The July burning was part of a general pogrom, in which a cripple, named Crowley, was deliberately shot by the police while in bed and several houses were set on fire while the people were asleep. A report was made to Dublin Castle by Mr. Hynes, the County Court Judge, who happened to be on the spot for quarter sessions. Questioned in the House of Commons, the Government refused to produce this report on the ground that production would not be in the public interest, which means – as Parliamentary experience teaches one – that it was damning to Government.

I am, Sir, your obedient servant,

J. Annan Bryce

Eccles Hotel, Glengarriff, County Cork, Sept. 25.

On 31 Oct 1920, John Annan Bryce wrote a letter which was published in The Times on 1 Nov 1920.

To the Editor of The Times

As reported in the papers today, my wife was arrested at Holyhead, deported to Kingstown, lodged in Bridewell there, and released without charge after four hours' detention. Such arrests are of daily occurrence in Ireland, where any and every interference with liberty had been legalized by recent legislation, but I am not aware under what authority they have become lawful in Great Britain.

My wife had been invited to address a meeting in Wales about reprisals, a subject on which she is a competent witness. As stated in my letter which you were good enough to publish on September 30, I mentioned that in 1916 she opened at Glengarriff the first convalescent home for officers in Ireland. Having lived there ever since, she has been able to see the effect of the policy of reprisals, and has suffered from them in her own person. Her garage has been burned (the claim for compensation had been passed by the County Court Judge), she had been repeatedly threatened – once officially, as described in my previous letter – with the burning down of her house, and on one occasion was in imminent danger of death from the rifle of a policeman.

Apart from the question of legality, and of the infliction of indignity on a person who at great trouble and expense has given patriotic service without any recognition, the arrest raises an issue of public interest. Government spokesmen minimize or altogether deny the reprisals. The Chief Secretary, in the debate of the 20th inst., even went so far as to deny that one single case had been put forward to justify Mr. Henderson's resolution, and last week had the assurance to impugn the statements of the correspondents of great English newspapers, men whose reputation for accuracy is at least equal to his own. The summary of outrages issued at the public expense by Dublin Castle as propaganda rarely mentions reprisals, and, when it does, leaves them to be ascribed to Sinn Fein. Government refuses to produce Judge Hynes's report on the Bantry reprisals of July 19. It prosecutes the Freeman's Journal before a tribunal of its own officials, but does not dare to prosecute before an English Court English newspapers making the same statements.

All this seems to indicate a determination to prevent the British public from learning the truth, and the arrest of my wife, when she attempts to perform what is surely the duty of a good citizen, appears to corroborate this view of the Government's attitude. The public has a right to demand that the truth shall no longer be concealed. If the Government has nothing to hide why does it not grant an impartial inquiry, such as that which investigated the German outrages in Belgium? The reprisal outrages in Ireland, if proved, are worse, in that Ireland is still part of the United Kingdom, not territory occupied in war. It is to be hoped that Lord Robert Cecil, whose intervention was greatly welcomed in Ireland, will again press for an inquiry, and that he and others on his side will, on the next occasion, support their speeches by their votes.

The public must not be fobbed off with a whitewashing inquiry like that into the Sheehy-Skeffington group of murders, the result of which only deepened Irish distrust of English justice. The inquiry must be comprehensive. Its purview should cover not only the reprisals themselves, but the authority under which they were committed, and the character and antecedents of their perpetrators. There is no reason to believe that some at least of the Black and Tans have been recruited from the same class as the notorious Hardy, released, at the instance of Mr Macpherson, to enter Government service after nine months of penal servitude under a sentence which required a minimum imprisonment of several years.

If Lord Robert Cecil returns to the charge, there is one point which he should bear in mind. Mr. Lloyd George, with apparent reason, retorted upon Mr. Asquith's accusation of the hellish policy of reprisals with a denunciation of the equally hellish policy of murder, but he did not remind the country of the fact that under Sir Henry Duke there were, for two years after rebellion, no murders of police, and that these murders began only after Mr. Shortt and Mr. McPherson, by their policy of repeated re-arrests on suspicion without charge, created a numerous class of active young men, who, deprived of the chance of legitimate occupation, took desperate courses. The same thing happened after Mr. Forster's Coercion Act of 1881. There is another point worth notice in connexion with my wife's arrest. She asked the arresting officer whether he was acting under the authority of Sir Hamar Greenwood or Sir N. Macready. He could not tell. In Ireland today one never can tell. In my letter to you of September 30 I mentioned that I had received no reply to my letter to him of September 16. I have since received the following answer:-

'Dublin Castle, October 2, 1920.

Dear Annan Bryce, I am in receipt of your letter of the 16th ultimo regarding the notice served by a military officer on the manageress of the Eccles Hotel, Glengarriff. I am passing your letter on to the Commander-in-Chief. Yours sincerely, Hamar Greenwood.'

As the reply is dated two days after the publication of my letter giving the answer of Sir N. Macready, Sir Hamar's only apparent object can have been to disclaim responsibility. Sir N. Macready disclaims responsibility for the Black and Tans. At one time Sir N. Macready was said to have authority over the police, but lately Sir H. Greenwood seems to have re-assumed responsibility for that force, and the other day he stated in the House that he was head of the Irish Government. All three – Sir Hamar, Sir Nevil, and General Tudor – disavow connivance at reprisals – in face of the fact that the reprisal threat described in my previous letter was typed on official paper bearing the Government water-mark S.O. and a crown. Condonation they cannot deny, for no one has been punished. Government should be pressed to declare under which thimble the pea is to be found, that one may not be shuttlecocked from one authority to another in search of redress.

I am, Sir, your obedient servant,

J. Annan Bryce

35 Bryanston Square, London. October 31.

On 8 Nov 1920, John Annan Bryce wrote a third letter which was published in The Times on 9 Nov 1920.

To the Editor of The Times

I have now received particulars of the arrest of my wife. Illustrating as they do the spirit and methods of the Irish Government, they are of general interest.

My wife crossed from Dublin by evening mail steamer on Friday, October 29. When about to leave the boat at Holyhead she was stopped on the companion stairs by an officer, who said, in a strong Ulster accent, 'You are wanted, and must go below.' The officer, a Captain Gallagher, refused to produce a warrant, and said he could not tell whether his orders came from Sir H. Greenwood or Sir N. Macready. Calling a woman dressed as a nurse, but whom my wife calls a wardress, he said. 'Take her in and search her.' That was done. Mrs. Bryce, aware of the dodger, usual in Ireland, of 'planting' compromising objects before a search, refused to let her luggage out of her sight, so Captain Gallagher proceeded to search it in her presence. Taking from her dispatch case a book entitled 'Ireland and Agriculture', he examined it curiously till shown the date, 1845. He then tore open her dressing-case, though offered her oath that it contained clothes only. 'I'm not believing your oath', he retorted and went on searching. As a result of the search he impounded only two papers, which I shall describe later. They have not been returned. Mrs Bryce had all through been protesting loudly, unwilling that the steamer staff should take her for a thief or murderer. She told the officer he should be ashamed of himself, whereupon he said gruffly to the wardress: 'Take her back, search her again, and take off her shoes.' Asked by Mrs Bryce what he proposed to do with her, he said he was awaiting instructions from Ireland, but that she would not be allowed to land and could sleep in a cabin with the wardress. This she refused to do, and went on deck, followed about by the wardress and soldiers. After an hour Captain Gallagher came and sat by her. He was now quite polite, Mrs Bryce gathering from his change of demeanour that he must have had fresh instructions from Ireland.

Eventually Mrs. Bryce was allowed to sleep alone in a cabin with a wardress outside. On the return of the steamer to Kingstown she was handed over by Captain Gallagher to an officer and five soldiers armed with rifles. The officer, cigarette in mouth, told her she must go to a motor, and marched her up the long length of the pier under the gaze of the occupants of the lines of trains about to depart for every quarter of Ireland. Arrived on the roadway at the pierhead she found the motor to be a common military lorry, open at both ends. Refusing to enter it, she was lifted in and pushed on to a seat. The soldiers and wardress got in, and the officer mounted beside the driver. A soldier next to her was smoking and kept his rifle between his knees. The jolting of the lorry, driven at high speed kept jerking this rifle over, so that at every bump it pointed at her face. She asked the officer to tell the soldier to hold his rifle so that it might not point at her. He replied, 'No, I won't.'

They drove to the Bridewell in Dublin, where Mrs Bryce was put into a bare-floored cell, all of stone, bitterly cold, dimly lighted, with wooded seats, and an open latrine in the corner. Breakfast was procured from an inn at her cost. After two hours, unable longer to bear the cold and stench, she rang a bell continuously till the turnkey let her out to sit with the warders in the corridor between the cells. After another hour and a half a young officer arrived from the Castle. Asked by Mrs. Bryce what was to be done with her, he said, 'I don't know. Isn't it true that you have been making political speeches in the South of Ireland?' She replied with indignation, 'It is absolutely untrue. I have made no political speeches in the South of Ireland. The whole thing is absolutely scandalous'.

She might have added that the only meetings she had addressed in Ireland were a recruiting meeting at Glengarriff in 1914 and various meetings there for the formation of an agricultural society, whose affairs she conducted with such success as to warrant a large grant from the County Council. It may further interest the 'competent military authority' under whose orders she is said to have been arrested, to hear that her grandfather, Sir George L'Estrange, Chamberlain under four Viceroys of Ireland, was rewarded by a commission in the Guards for having raised a regiment in the Peninsular War; that her father was a first captain (major) in the Royal Artillery, and a resident magistrate in Ireland for 30 years; that she herself, before equipping and opening the convalescent home for officers at Glengarriff, worked for many months with the French Army at Compiegne, and that on her suggestion the band of the Irish Guards was sent over to Ireland, with an excellent effect on enlistment. After another hour a warder told her she might go, there being no charge against her.

My wife is brave and has been strong, but she is severely shaken by ill-usage on this and previous occasions at the hands of servants of the Crown. For such opprobrious maltreatment she might have expected from a gentleman in the position of Chief Secretary, when he found the case to have been trumped up, an offer of reparation with a frank apology. But no: he proceeded to aggravate the offence by an injurious insinuation wrapped up with a grudging admission. Answering Mr. Hodge, he said that Mrs. Bryce had documents, but not of sufficiently serious a nature to lay a charge, the implication being that they were of a serious nature. Moreover, the mere use of the term 'document' itself was calculated to produce a misleading impression on the ordinary mind, which thinks of a document as something formal and important. The word is not properly descriptive of the papers taken from my wife. As I have already said, they were in number two. One was a writing-pad with jottings for her speech in Wales. If this paper incriminated anyone it was the Government, not herself. The other paper was a cartoon from a London newspaper, the Catholic Herald. It represents a black and tan dog with a pool of blood in front, while John Bull and Uncle Sam look on, the latter – 'This dog is mad. If you don't look out it will bite you soon.' Some people are disposed to regard this sinister prediction as already far on its way to fulfilment.

The Chief Secretary told Mr. Devlin last week that he would welcome the evidence of eye-witnesses, but when a competent eyewitness of repute tries to land in England he arrests her without warrant, deports her back to Ireland, and confines her in a noisome jail with every circumstance of indignity. When such treatment is inflicted on a person against whom no charge can be made, who has performed national service of many kinds, and who can make her voice heard, your readers may judge what chance against treatment infinitely more savage have thousands of men, women and children, innocent of politics, low in station, and powerless to make their voice heard. As a local official, who feared an irruption of Black and Tans, said to me: 'We poor Hottentots of Irish can't make our voices heard in England.' They suffer constant threats of reprisal, raids by night and by day, continual lootings, prohibition of markets and fairs, wreckings and burnings of houses, shops and factories, bombings, shootings, killings, and countless other outrages, many never reported. My own village of Glengarriff was shot up in August. Every soul fled to the mountains, woods or fields, work was suspended for weeks, and even now many fear to sleep in their houses. We used to call Prussian methods brutal and stupid. The methods of the Irish Government are not less brutal, but more stupid, for while the Prussian methods had the approval of the German people the Irish methods, once they are known of the British people, will be loathed, except in the House of Commons.

My narrative involves other questions, one of importance to every citizen, that of the legality of arrest without warrant. On Monday last the House of Commons with as little care for liberty as the Star Chamber days, twice lent itself to the burking of discussion. In the afternoon only three members of the old law and order party, Lord Robert Cecil, Mr. Mosley, and Mr. Bottomley, and one Liberal Coalitionist, Major Breese, supported Mr. Hogges.

The Chief Secretary now seems to feel that he was on doubtful ground when on Monday he based himself on the Irish Act. By Wednesday he had consulted Sir Gordon Hewart, and now puts his reliance first on D.O.R.A., with the Irish Act as second leg. The straddle won't work. A ship at Holyhead is either in England or it is not. If it is and D.O.R.A. supposed for such purposes to be dead, is yet alive, the British people have notice that on the whim of an official they may be arrested, deported, and imprisoned without warrant. The Chief Secretary goes further. In his opinion even the Irish Act can in some cases be applied in England. The British people should take good note of that. This is a matter which cannot be allowed to rest.

There is another point not yet made clear. From whom is my wife to obtain redress? Who is the competent military authority under whose order the arrest was made? Under which thimble is the pea in this case? The Chief Secretary says he is head of the Irish Government. Was the arrest made with his knowledge? It is incredible that he can have countenanced anything so foolish. Nor do I believe that the order came from Sir N. Macready. From whom, then? Presumably from General Tudor, who seems to act independently of, though, as the Granard reprisals show, in combination when necessary, with, the other two arms. In Ireland people think that the Castle, that is, the civil authority, has nothing to do with the present policy, and that view has corroboration from the rapid successive supersessions of Inspectors General Byrne and Smith, the latter an Ulsterman and strong Unionist. The belief is that the motive power at present lies with a clique in London whose orders are executed by General Tudor, with the assistance, when required, but without the foreknowledge, of Sir N. Macready and the Castle.

Some of the incidents of the narrative throw an unpleasant light on the conduct of the Army in Ireland. The smoking of officers and men on duty, trivial in itself, indicates a decline in discipline. Till this year soldiers and people were still on the best of terms, but most of the soldiers are mere boys taking their colour from evil surroundings, and the decay of discipline has of late, with reprisals, being increasing in frequency, and in savagery has become more marked. The position is regarded with alarm in the highest quarters, and experienced officers tell me that it would be impossible to send abroad the regiments now serving in Ireland. Sir Nevil Macready long ago saw the danger and in August issued a proclamation against reprisals, but his delicacy about acting on it has had results ruinous to the Army, disastrous to Ireland, and detrimental to the prestige of the Empire.

J. Annan Bryce.

35, Bryanston Square, London. Nov. 8.

The hotel web site says it was leased to the British War Office from 1918 to 1920. During this time it was known as the Queen Alexandria Home of Rest for Officers and was occupied by soldiers recuperating from the trauma of World War One. It cost one guinea (€1.90) per week for full board with fishing and shooting rights. From 1920 to 1921 the hotel was occupied by troops of the Essex Regiment. No mention of ADRIC

Neither this nor the following report seems to identify the command chain(s) to which the bullying assailants belonged – it's not entirely clear whether they were serving British soldiers, Black and Tans (ruffians recruited from demobbed NCO's and OR's) or the Auxiliaries (intimidators and assassins recruited from demobbed ex-officers). This of course enabled the authorities to disclaim responsibility from every side.

www.atholbooks.org/archives/cands/cs_articles/bryce.php (now discontinued)

From Church & State: Autumn 2006

The Crown's Campaign Against Protestant Neutrality In Cork

During The Irish War Of Independence

Eamon Dyas

Modern day Bantry continues to bear witness to an event that in 1920 caused a bit of a stir in England and helped throw light on one aspect of the activities of the Crown forces in Ireland during the War of Independence.

The central characters were Mr. and Mrs. Annan Bryce, an old couple who had made their home in Bantry ... He had been Liberal MP for Inverness Burghs from 1906 until 1918 when the constituency was dissolved ... His wife, Violet, came from a British military family and when war was declared she, like her husband, was eager to serve King and country. Towards that end in 1916 she purchased the Eccles Hotel in Glengarriff and converted it into a convalescent home for officers in Ireland – the first in the country ...

Under normal circumstances the couple would have adopted to a quiet but active retirement in Cork. He with his interest in gardening and she with her hotel. However, they were living in difficult times and found themselves in a situation where the society around them was in the process of giving birth to a new state but where the old state was refusing to give ground and attempting to compensate for its lack of social support by reliance on military power.

Despite the turmoil of the military situation in Ireland in 1920 the establishment credentials of both Mr. and Mrs. Annan Bryce would seem to have been a guarantee of protection by Crown forces. He, after all, was the brother of an ex-Chief Secretary for Ireland and in his own right a respected member of British society and she, coming from a British military family, had been the benefactor and comforter of British soldiers in the country during the previous war. Then, in late September 1920, came a letter from John Annan Bryce that caused a stir among the British establishment when it was published in The Times.

Reporting the Irish situation in The Times

The Times since Henry Wickham Steed assumed the editorship in 1919 had begun to make serious efforts to use its influence to formulate a solution to the Irish crisis. Steed was by no means the champion of Ireland but he was a faithful servant of British interests and viewed the Irish problem as something that got in the way of those interests. He was eager to ensure that post-WW1 Britain adjusted to the new world situation which saw an emerging US increasingly calling the shots. He viewed post-war British interests as requiring a re-drawing of the map of Europe particularly the break-up of Austria-Hungary (a project on which he had been actively engaged on behalf of the British government during the War). The ratification of the Treaty of Versailles and the involvement by the US in the emerging League of Nations would help ensure the sustainability of the new Europe and it was therefore important that the US sign up to it. Although President Wilson had agreed to the terms of the Treaty it was necessary to have it ratified by the US Senate and Congress. Thus, much of Steed's concern during his editorship was to have the Treaty ratified. (Although the US never did ratify the Treaty and never joined the League of Nations, it was not until the Treaty of Berlin in August 1921 when the US went its own way in formally ending its war with Germany, that the possibility of US ratification was laid to rest).

As far as Steed was concerned, the Irish problem was getting in the way of American co-operation and therefore every effort had to be made to find a solution short of offering the country full independence. Aside from the stubborn insistence of the Irish to have independence another major obstacle was closer to home. Steed recognised that the failure of the old Imperial Unionists within the establishment to see the new geopolitical reality was something that needed to be neutralised. It was therefore necessary to utilise middle-class public opinion in the new British democracy to shake them up. But, as someone who continued to believe that the retention of Ireland within the Empire was also critical to British interests he was forced to tread a very delicate line. One way he did that was to ensure a regular publication of honest reports of what was happening in Ireland alongside the views of Imperial Unionist as well as the propaganda of the Irish military establishment.

The Times and Crown intimidation of Protestant loyalists

That then is the context of the following series of letters published in The Times in 1920. It is one old couple's account of their treatment at the hands of the Crown forces. What gave it its impact was the fact of who this old couple were, what they experienced, and their tenacity in pursuing what they viewed as a gross injustice. All headings are as they appeared in the paper.

From The Times, September 30, 1920.

REPRISAL THREATS: Notice by Circular.

To the Editor of The Times

Sir – on September 16, at 9.45 a.m., a lorry full of soldiers from Bantry stopped in front of the Eccles Hotel, Glengarriff, where I have been staying since August 19. The manageress went to the door and was handed by a soldier an envelope addressed in handwriting 'The Manageress, Eccles Hotel, Glengarriff.' It contained an unsigned and undated slip worded as follows:-

'In some districts loyalists and members of his Majesty's forces have received notices threatening the destruction of their houses in certain eventualities. Under these circumstances it has been decided that for each loyalist's house so destroyed the house of a republican leader will be similarly dealt with. It is naturally to be hoped that the necessity for such reprisal will not arise and therefore this warning of the punishment which will follow any destruction of loyalists' houses will be widely circulated.'

I at once sent a copy of this notice, mentioning the circumstances, to General Sir Nevil Macready, and said that, as it was contrary to his recent proclamation against reprisals, I presumed it was issued without his authority or knowledge. I received, to my surprise, the following reply:-

'Sir, – Sir Nevil Macready asks me in reply to your letter of the 16th instant to state that he is acquainted with the distribution of the notices, a copy of which you enclosed. Truly yours, William Rycroft, Major-General i/c Administration, Ireland, G.H.Q. Parkgate, Dublin, 18 September, 1920.'

On the 17th inst. I wrote a similar letter, with copy of notice to the O.C., Bantry, asking that , as on the night of August 15 the large garage of this hotel had been burned by the police who had also threatened to burn the hotel itself, he would give an assurance against further molestation. I gave him as a special reason for protection that the present proprietress had acquired the hotel in 1916 for conversion into a convalescent hospital for officers, that it was the first such hospital in Ireland, and that with the title of 'Queen Alexandra's Home of Rest for Officers,' first under the Red Cross and afterwards the Dublin Command, it had – she being commandant – housed hundreds of wounded officers, while the only return for her pains and expenditure of many thousand pounds, which both the Red Cross and the War Office refust to repay, had been the burning of the garage. To this letter I received the following Gilbertian answer:-

'To J. Annan Bryce, Esq., Eccles Hotel, Glengarriff. In reply to your letter of September 17, 1920, addressed to O.C. Barracks, Bantry. It appears that slips similar to the one to which you evidently refer are being distributed about the country. On investigation I find that an officer of my battalion picked one of them up. This officer having seen similar slips in Bantry and other places thought it would be a good thing to hand it in to one of the hotels in Glengarriff as he passed through. As yours was the most convenient, being close to the road, he put it in an envelope and addressed it to the manageress and handed it in as he passed. L.M. Jones, Lieutenant-Colonel, Commanding Troops, Bantry and commanding 1st Battalion The King's Regiment. Bantry, September 20, 1920.'

I also wrote to Sir Hamar Greenwood, but have received no reply. It will be seen that neither Sir Nevil Macready nor Colonel Jones disavows the notice, and that Colonel Jones makes no answer to the request for an assurance of non-molestation.

I may add that there is no justification for the issue of such a notice in this district, where the only damage to loyalists premises has been done by the police. In July they burned the stores of Mr. G.W. Biggs, the principal merchant in Bantry, a man highly respected, a Protestant, and a lifelong Unionist, with a damage of over £25,000, and the estate office of the late Mr. Leigh-White, also a Unionist. Subsequently, in August, the police fired into Mr. Biggs's office, while his residence has since been commandeered for police barracks. He has had to send his family to Dublin and to live himself in a hotel. Only two reasons can be assigned for the outrages on Mr. Biggs, one that he employed Sinn Feiners – he could not work his large business without them, there being no Unionist workmen in Bantry – the other a recently published statement of his protesting – on his own 40 years' experience – against Orange allegations of Catholic intolerance.

The July burning was part of a general pogrom, in which a cripple, named Crowley, was deliberately shot by the police while in bed and several houses were set on fire while the people were asleep. A report was made to Dublin Castle by Mr. Hynes, the County Court Judge, who happened to be on the spot for quarter sessions. Questioned in the House of Commons, the Government refused to produce this report on the ground that production would not be in the public interest, which means – as Parliamentary experience teaches one – that it was damning to Government.

I am, Sir, your obedient servant,

J. Annan Bryce

Eccles Hotel, Glengarriff, County Cork, Sept. 25.

[In point of fact Sir Nevil Macready was being disingenuous in his reply to Annan Bryce. It was on his personal instructions that the circular was drawn up and distributed – see his autobiography Annals Of An Active Life, vol. 2, page 497. Needless to say, he does not mention the Annan Bryce incident in his autobiography. – ED]

The Arrest of Mrs. Bryce

Mr. and Mrs. Annan Bryce were obviously a strong-willed couple. John Annan Bryce was over 77 years old when he confronted his persecutors in September 1920 and his wife could not have been much younger. Incensed by her treatment, just over a month later she agreed to visit Tonypandy in Wales to address a meeting on British reprisals in Ireland. Her experience is again told in a letter by her husband to The Times.

From The Times, November 1, 1920.

IRISH REPRISALS: The Public Claim to Truth.

Arrest of Mrs Annan Bryce

To the Editor of The Times.

Sir – as reported in the papers today, my wife was arrested at Holyhead, deported to Kingstown, lodged in Bridewell there, and released without charge after four hours' detention. Such arrests are of daily occurrence in Ireland, where any and every interference with liberty had been legalized by recent legislation, but I am not aware under what authority they have become lawful in Great Britain.

My wife had been invited to address a meeting in Wales about reprisals, a subject on which she is a competent witness. As stated in my letter which you were good enough to publish on September 30, I mentioned that in 1916 she opened at Glengarriff the first convalescent home for officers in Ireland. Having lived there ever since, she has been able to see the effect of the policy of reprisals, and has suffered from them in her own person. Her garage has been burned (the claim for compensation had been passed by the County Court Judge), she had been repeatedly threatened – once officially, as described in my previous letter – with the burning down of her house, and on one occasion was in imminent danger of death from the rifle of a policeman.

Apart from the question of legality, and of the infliction of indignity on a person who at great trouble and expense has given patriotic service without any recognition, the arrest raises an issue of public interest. Government spokesmen minimize or altogether deny the reprisals. The Chief Secretary, in the debate of the 20th inst., even went so far as to deny that one single case had been put forward to justify Mr. Henderson's resolution, and last week had the assurance to impugn the statements of the correspondents of great English newspapers, men whose reputation for accuracy is at least equal to his own. The summary of outrages issued at the public expense by Dublin Castle as propaganda rarely mentions reprisals, and, when it does, leaves them to be ascribed to Sinn Fein. Government refuses to produce Judge Hynes's report on the Bantry reprisals of July 19. It prosecutes the Freeman's Journal before a tribunal of its own officials, but does not dare to prosecute before an English Court English newspapers making the same statements.

All this seems to indicate a determination to prevent the British public from learning the truth, and the arrest of my wife, when she attempts to perform what is surely the duty of a good citizen, appears to corroborate this view of the Government's attitude. The public has a right to demand that the truth shall no longer be concealed. If the Government has nothing to hide why does it not grant an impartial inquiry, such as that which investigated the German outrages in Belgium? The reprisal outrages in Ireland, if proved, are worse, in that Ireland is still part of the United Kingdom, not territory occupied in war. It is to be hoped that Lord Robert Cecil, whose intervention was greatly welcomed in Ireland, will again press for an inquiry, and that he and others on his side will, on the next occasion, support their speeches by their votes.

The public must not be fobbed off with a whitewashing inquiry like that into the Sheehy-Skeffington group of murders, the result of which only deepened Irish distrust of English justice. The inquiry must be comprehensive. Its purview should cover not only the reprisals themselves, but the authority under which they were committed, and the character and antecedents of their perpetrators. There is no reason to believe that some at least of the Black and Tans have been recruited from the same class as the notorious Hardy, released, at the instance of Mr Macpherson, to enter Government service after nine months of penal servitude under a sentence which required a minimum imprisonment of several years.

If Lord Robert Cecil returns to the charge, there is one point which he should bear in mind. Mr. Lloyd George, with apparent reason, retorted upon Mr. Asquith's accusation of the hellish policy of reprisals with a denunciation of the equally hellish policy of murder, but he did not remind the country of the fact that under Sir Henry Duke there were, for two years after rebellion, no murders of police, and that these murders began only after Mr. Shortt and Mr. McPherson, by their policy of repeated re-arrests on suspicion without charge, created a numerous class of active young men, who, deprived of the chance of legitimate occupation, took desperate courses. The same thing happened after Mr. Forster's Coercion Act of 1881.

There is another point worth notice in connexion with my wife's arrest. She asked the arresting officer whether he was acting under the authority of Sir Hamar Greenwood or Sir N. Macready. He could not tell. In Ireland today one never can tell. In my letter to you of September 30 I mentioned that I had received no reply to my letter to him of September 16. I have since received the following answer:-

'Dublin Castle, October 2, 1920.

Dear Annan Bryce, I am in receipt of your letter of the 16th ultimo regarding the notice served by a military officer on the manageress of the Eccles Hotel, Glengarriff. I am passing your letter on to the Commander-in-Chief. Yours sincerely, Hamar Greenwood.'

As the reply is dated two days after the publication of my letter giving the answer of Sir N. Macready, Sir Hamar's only apparent object can have been to disclaim responsibility. Sir N. Macready disclaims responsibility for the Black and Tans. At one time Sir N. Macready was said to have authority over the police, but lately Sir H. Greenwood seems to have re-assumed responsibility for that force, and the other day he stated in the House that he was head of the Irish Government. All three – Sir Hamar, Sir Nevil, and General Tudor – disavow connivance at reprisals – in face of the fact that the reprisal threat described in my previous letter was typed on official paper bearing the Government water-mark S.O. and a crown. Condonation they cannot deny, for no one has been punished. Government should be pressed to declare under which thimble the pea is to be found, that one may not be shuttlecocked from one authority to another in search of redress.

I am, Sir, your obedient servant,

J. Annan Bryce

35 Bryanston Square, London. October 31.

The House of Commons and the arrest of Mrs Bryce.

Following the publication of these letters in The Times, questions were asked in the House of Commons. Mr. Hogge (Edinburgh E.L.) asked Sir Hamar Greenwood under what legislation Mrs. Annan Bryce had been arrested at Holyhead. Greenwood replied that she had been arrested under the powers conferred by the Restoration of Order (Ireland) Act. The following interaction then ensued: –

Mr. HOGGE. – When and how have the Government power under the Restoration of Order (Ireland) Act to arrest a British subject in this country? Is it not the fact that that Act applies only to Ireland? This lady, the wife of an ex-member of this House – The SPEAKER interrupts – The hon. Member must give notice of that question. It requires research. – Mr. Hogge. – I did give notice of this question as early as half-past 11 o'clock this morning. The reply is: – 'Under the Restoration of Order (Ireland) Act'. Anybody in this House knows that that Act was passed for Ireland. I am not asking a question about Ireland. I want to know under what authority the arrest was made in this country under an Act which applies only to Ireland. – The SPEAKER again – If the hon. Member puts that question in the ordinary way he will get a reply. Mr. HOGGE later asked leave to move the adjournment of the House in order to call attention to Mrs. Annan Bryce's arrest as a definite matter of urgent public importance. On the Speaker putting the usual question, 36 members rose in their places, Lord R. Cecil being the only supporter on the Ministerial side. As the matter fell short of the necessary number by four, leave was refused. (Report in The Times, 2 November 1920.)

A couple of days later the issue was once more raised in the House: –

Major ENTWISTLE (Kingston-upon-Hull, S.W. L.) asked the Chief Secretary under what authority the officer who arrested Mrs. Annan Bryce at Holyhead made the arrest.

Sir H. GREENWOOD. – I would refer the hon. member to Regulation 55 of the Defence of the Realm Regulations, and number 55 of the Restoration of Order (Ireland) Regulations. The officer who arrested her was duly authorised by the competent military authority, and it was unnecessary therefore, for him to produce a warrant for her arrest.

Mr. MACVEAGH asked whether the Restoration of Order (Ireland) Act applied to Holyhead, which happened to be in Wales (Hear, hear). Sir H. GREENWOOD. – In some cases. In my opinion, it does. Mr MACVEAGH – Will the right hon. gentleman tell us exactly what offence was committed by Mrs. Annan Bryce?

Mr HOGGE asked whether he would state under what authority persons were being arrested and detained in this country without the authorities producing a warrant or making any charge.

Sir G. HEWART, Attorney-General (Leicester E. C.L.), who replied said:- I do not know what cases, if any, are referred to in the question, but Regulation 55 of the Defence of the Realm Regulations provides that any person authorised for the purpose by the competent naval or military authority, or any police constable or officer of Customs or Exercise, or aliens officer, may arrest without warrant any person whose behaviour is of such a nature as to give reasonable grounds for suspecting that he has acted, or is acting, or is about to act in a manner prejudicial to the public safety of the defence of the realm.

Mr. HOGGE asked whether it was under this authority that Mrs Annan Bryce was arrested and detained at Holyhead? – Sir G. Hewart. – I cannot say. Mr. Hogge – Will my right hon. friend inquire if I put down a question two days hence? Sir G. Hewart. – I will certainly inquire. (Laughter). (Report in The Times, 4 November 1920.)

The issue remained in the House over a week later when Lloyd George, the Prime Minister became involved: –

Sir H. GREENWOOD, in reply to Mr. Hogge, said that the officer who effected the arrest of Mrs. Annan Bryce was under the control of the Secretary of State for War, but he (Sir H. Greenwood) was prepared to take full responsibility for that arrest. It was not the case that it was admitted that there was no ground for arresting Mrs Bryce, and in view of the fact that the documents found on her contained gross libels on the Royal Irish Constabulary, he could not agree that any apology or redress was due from the Government.

Mr. HOGGE asked the Prime Minister whether he could state the offence which Mrs. Annan Bryce was suspected of having committed, and whether he, as a Liberal, agreed with this invasion of personal liberty.

Mr LLOYD GEORGE. – The actions taken by Sir H. Greenwood and those associated with him in the Government of Ireland are for the defence and protection of liberty (cheers), and, therefore, I certainly, as a Liberal support fully the action taken (cheers). Sir D. MACLEAN (Peebles and Southern, L.). – Is the Prime Minister aware that very high legal authorities are of opinion that the action of the Executive in arresting Mrs Bryce was wholly illegal? (Cries of 'Name' and 'Take action then').

Mr LLOYD GEORGE – If any illegality was committed, it was committed in this country, and the courts are open, and, therefore, if that is the case it is not for me to advance any opinion.

Mr. DEVLIN (Belfast, Falls, Nat.) – If Mrs Bryce was arrested for an offence, why was she not tried for it?

Mr. LLOYD GEORGE – When there are so many outrages committed in Ireland, and when there is a widespread conspiracy, the police are entitled to take precautions. (Hear, hear). Whether in this particular case the precautions were necessary or not, Sir H. Greenwood has already given the answer, but they are entitled to make an examination and to search where there is suspicion. That is the only way they can protect themselves. (Cheers).

Replying to further questions, Mr. LLOYD GEORGE said he was making no suggestion at all about Mrs. Annan Bryce. He was only saying that the police were entitled to take steps of this character where they suspected that any person had got either information or documents which they thought would interfere with the carrying out of the law in Ireland. (Cheers). If you interfered with the discretion of the police in this respect and said, 'You must not exercise your functions if a person happens to be eminent' it would be quite impossible afterwards to expect them to take the risks which they were taking in carrying out their duties. (Cheers). (Report in The Times, 12 November 1920.)

The Final Revelations

In the meantime a final long letter from Annan Bryce was given a prominent position in The Times.

From The Times, November 9, 1920.

IRISH REPRISALS.

Arrest of Mrs Annan Bryce: A sinister portent.

To the Editor of The Times.

Sir, – I have now received particulars of the arrest of my wife. Illustrating as they do the spirit and methods of the Irish Government, they are of general interest.

My wife crossed from Dublin by evening mail steamer on Friday, October 29. When about to leave the boat at Holyhead she was stopped on the companion stairs by an officer, who said, in a strong Ulster accent, 'You are wanted, and must go below.' The officer, a Captain Gallagher, refused to produce a warrant, and said he could not tell whether his orders came from Sir H. Greenwood or Sir N. Macready. Calling a woman dressed as a nurse, but whom my wife calls a wardress, he said. 'Take her in and search her.' That was done. Mrs. Bryce, aware of the dodger, usual in Ireland, of 'planting' compromising objects before a search, refused to let her luggage out of her sight, so Captain Gallagher proceeded to search it in her presence. Taking from her dispatch case a book entitled 'Ireland and Agriculture', he examined it curiously till shown the date, 1845. He then tore open her dressing-case, though offered her oath that it contained clothes only. 'I'm not believing your oath', he retorted and went on searching. As a result of the search he impounded only two papers, which I shall describe later. They have not been returned. Mrs Bryce had all through been protesting loudly, unwilling that the steamer staff should take her for a thief or murderer. She told the officer he should be ashamed of himself, whereupon he said gruffly to the wardress: 'Take her back, search her again, and take off her shoes.' Asked by Mrs Bryce what he proposed to do with her, he said he was awaiting instructions from Ireland, but that she would not be allowed to land and could sleep in a cabin with the wardress. This she refused to do, and went on deck, followed about by the wardress and soldiers. After an hour Captain Gallagher came and sat by her. He was now quite polite, Mrs Bryce gathering from his change of demeanour that he must have had fresh instructions from Ireland.

Eventually Mrs. Bryce was allowed to sleep alone in a cabin with a wardress outside. On the return of the steamer to Kingstown she was handed over by Captain Gallagher to an officer and five soldiers armed with rifles. The officer, cigarette in mouth, told her she must go to a motor, and marched her up the long length of the pier under the gaze of the occupants of the lines of trains about to depart for every quarter of Ireland. Arrived on the roadway at the pierhead she found the motor to be a common military lorry, open at both ends. Refusing to enter it, she was lifted in and pushed on to a seat. The soldiers and wardress got in, and the officer mounted beside the driver. A soldier next to her was smoking and kept his rifle between his knees. The jolting of the lorry, driven at high speed kept jerking this rifle over, so that at every bump it pointed at her face. She asked the officer to tell the soldier to hold his rifle so that it might not point at her. He replied, 'No, I won't.'

They drove to the Bridewell in Dublin, where Mrs Bryce was put into a bare-floored cell, all of stone, bitterly cold, dimly lighted, with wooded seats, and an open latrine in the corner. Breakfast was procured from an inn at her cost. After two hours, unable longer to bear the cold and stench, she rang a bell continuously till the turnkey let her out to sit with the warders in the corridor between the cells. After another hour and a half a young officer arrived from the Castle. Asked by Mrs. Bryce what was to be done with her, he said, 'I don't know. Isn't it true that you have been making political speeches in the South of Ireland?' She replied with indignation, 'It is absolutely untrue. I have made no political speeches in the South of Ireland. The whole thing is absolutely scandalous'.

She might have added that the only meetings she had addressed in Ireland were a recruiting meeting at Glengarriff in 1914 and various meetings there for the formation of an agricultural society, whose affairs she conducted with such success as to warrant a large grant from the County Council. It may further interest the 'competent military authority' under whose orders she is said to have been arrested, to hear that her grandfather, Sir George L'Estrange, Chamberlain under four Viceroys of Ireland, was rewarded by a commission in the Guards for having raised a regiment in the Peninsular War; that her father was a first captain (major) in the Royal Artillery, and a resident magistrate in Ireland for 30 years; that she herself, before equipping and opening the convalescent home for officers at Glengarriff, worked for many months with the French Army at Compiegne, and that on her suggestion the band of the Irish Guards was sent over to Ireland, with an excellent effect on enlistment. After another hour a warder told her she might go, there being no charge against her.

My wife is brave and has been strong, but she is severely shaken by ill-usage on this and previous occasions at the hands of servants of the Crown. For such opprobrious maltreatment she might have expected from a gentleman in the position of Chief Secretary, when he found the case to have been trumped up, an offer of reparation with a frank apology. But no: he proceeded to aggravate the offence by an injurious insinuation wrapped up with a grudging admission. Answering Mr. Hodge, he said that Mrs. Bryce had documents, but not of sufficiently serious a nature to lay a charge, the implication being that they were of a serious nature. Moreover, the mere use of the term 'document' itself was calculated to produce a misleading impression on the ordinary mind, which thinks of a document as something formal and important. The word is not properly descriptive of the papers taken from my wife. As I have already said, they were in number two. One was a writing-pad with jottings for her speech in Wales. If this paper incriminated anyone it was the Government, not herself. The other paper was a cartoon from a London newspaper, the Catholic Herald. It represents a black and tan dog with a pool of blood in front, while John Bull and Uncle Sam look on, the latter – 'This dog is mad. If you don't look out it will bite you soon.' Some people are disposed to regard this sinister prediction as already far on its way to fulfilment.

The Chief Secretary told Mr. Devlin last week that he would welcome the evidence of eye-witnesses, but when a competent eyewitness of repute tries to land in England he arrests her without warrant, deports her back to Ireland, and confines her in a noisome jail with every circumstance of indignity. When such treatment is inflicted on a person against whom no charge can be made, who has performed national service of many kinds, and who can make her voice heard, your readers may judge what chance against treatment infinitely more savage have thousands of men, women and children, innocent of politics, low in station, and powerless to make their voice head. As a local official, who feared an irruption of Black and Tans, said to me: 'We poor Hottentots of Irish can't make our voices head in England.' They suffer constant threats of reprisal, raids by night and by day, continual lootings, prohibition of markets and fairs, wreckings and burnings of houses, shops and factories, bombings, shootings, killings, and countless other outrages, many never reported. My own village of Glengarriff was shot up in August. Every soul fled to the mountains, woods or fields, work was suspended for weeks, and even now many fear to sleep in their houses. We used to call Prussian methods brutal and stupid. The methods of the Irish Government are not less brutal, but more stupid, for while the Prussian methods had the approval of the German people the Irish methods, once they are known of the British people, will be loathed, except in the House of Commons.

My narrative involves other questions, one of importance to every citizen, that of the legality of arrest without warrant. On Monday last the House of Commons with as little care for liberty as the Star Chamber days, twice lent itself to the burking of discussion. In the afternoon only three members of the old law and order party, Lord Robert Cecil, Mr. Mosley, and Mr. Bottomley, and one Liberal Coalitionist, Major Breese, supported Mr. Hogges.

The Chief Secretary now seems to feel that he was on doubtful ground when on Monday he based himself on the Irish Act. By Wednesday he had consulted Sir Gordon Hewart, and now puts his reliance first on D.O.R.A., with the Irish Act as second leg. The straddle won't work. A ship at Holyhead is either in England or it is not. If it is and D.O.R.A. supposed for such purposes to be dead, is yet alive, the British people have notice that on the whim of an official they may be arrested, deported, and imprisoned without warrant. The Chief Secretary goes further. In his opinion even the Irish Act can in some cases be applied in England. The British people should take good note of that. This is a matter which cannot be allowed to rest.

There is another point not yet made clear. From whom is my wife to obtain redress? Who is the competent military authority under whose order the arrest was made? Under which thimble is the pea in this case? The Chief Secretary says he is head of the Irish Government. Was the arrest made with his knowledge? It is incredible that he can have countenanced anything so foolish. Nor do I believe that the order came from Sir N. Macready. From whom, then? Presumably from General Tudor, who seems to act independently of, though, as the Granard reprisals show, in combination when necessary, with, the other two arms. In Ireland people think that the Castle, that is, the civil authority, has nothing to do with the present policy, and that view has corroboration from the rapid successive supersessions of Inspectors General Byrne and Smith, the latter an Ulsterman and strong Unionist. The belief is that the motive power at present lies with a clique in London whose orders are executed by General Tudor, with the assistance, when required, but without the foreknowledge, of Sir N. Macready and the Castle.

Some of the incidents of the narrative throw an unpleasant light on the conduct of the Army in Ireland. The smoking of officers and men on duty, trivial in itself, indicates a decline in discipline. Till this year soldiers and people were still on the best of terms, but most of the soldiers are mere boys taking their colour from evil surroundings, and the decay of discipline has of late, with reprisals, being increasing in frequency, and in savagery has become more marked. The position is regarded with alarm in the highest quarters, and experienced officers tell me that it would be impossible to send abroad the regiments now serving in Ireland. Sir Nevil Macready long ago saw the danger and in August issued a proclamation against reprisals, but his delicacy about acting on it has had results ruinous to the Army, disastrous to Ireland, and detrimental to the prestige of the Empire.

J. Annan Bryce.

35, Bryanston Square, London. Nov. 8.

This letter was John Annan Bryce's final salvo in his struggle with the Crown authorities in Ireland and he died in 1923. His wife also appears to have been discouraged from taking any further public stance on the issue of reprisals (a result that was undoubtedly the intention behind her arrest and harassment).

Protestant Loyalist Neutrals during the War of Independence

The above correspondence is important in a number of ways. Not least because of the insight it offers into the difficulties of those Protestants in Cork who were placed in an impossible position by the Crown authorities. As Annan Bryce points out in his first letter (30 September 1920), in his experience, the only damage to loyalist premises in his area had been done by police and he cites a number of examples including the burning down by police of the stores owned by G.W. Biggs, a Protestant and lifelong Unionist. His explanation for this treatment is that Biggs employed Sinn Fein workers (a situation which Bryce states was difficult to avoid in Bantry where most of the local workforce were Sinn Fein supporters) and that Biggs had the audacity to have published a statement contradicting Orange claims of Catholic intolerance against Protestants in the area. The situation of neutral Protestant loyalists was further exacerbated by the proclamation of General Strickland some months later. Here is a report, again from The Times that reveals the difficulties in which many Protestants were placed by the action of the British military authorities.

From The Times, January 27, 1921.

Rebels in British Uniform.

(from our correspondent)

New facts concerning the execution by a 'Republican Court-martial of a Protestant farmer named John Bradfield, on his farmstead, near Bandon, Co. Cork, last Monday, show the terrible position in which loyalists in the martial law area are placed.

Under General Strickland's proclamation they are required to give information, under pain of prosecution, of facts which may be within their knowledge of arrangements for ambushes, carrying of arms, and so forth – in short, it is an offence to remain neutral. Yet if they give such information they incur the risk of rebel vengeance. This state of things has aroused many protests form loyalists in the South of Ireland, who point out that, if it became known that they intended to comply with the Government's order, their lives would not be worth 24 hours' purchase. On the day before his death John Bradfield was visited by six men in military uniform, ostensibly officers of his Majesty's forces, who questioned him about the movements of Sinn Feiners in his district. What information he gave, if any, is not known, but it is now stated that his visitors were Republicans masquerading as British officers, and the unfortunate man fell readily into the trap laid for him. After he was shot, a note was found pinned to his clothing stating that he had been shot following a Court martial held the previous night, at which he had been found guilty of having attempted to inform the enemy of the presence and movements of Republican troops.