Walter Wardlaw (William) Waddell

(16 Feb 1913 – 11 Sep 1979)

There are many variants of the proverb that (to quote one at random) the cobbler's family go unshod, and in a sense it is true here in that I've focussed on sometimes distant and long-dead ancestors instead of the closer relatives that I knew and in most cases cared deeply about.

But it does make practical sense – did Beethoven start with a Choral Symphony – or Mozart with the Jupiter? If not them, then certainly not me in my own infinitely lesser undertaking and with not one single gene for genius.

Another practical consideration is that I know so little about them. They didn't go on to higher education or write any books or learned articles, for example, or go into public life, and so there is no audit trail for Google to pick up. And there was very little oral tradition within the family, no family portraits or festive celebrations of birthdays or wedding anniversaries, and so on. And there was a defensive wall of secrecy or evasiveness which severely discouraged direct questions about their personal journeys. But I can recollect, or have recently come across, some scraps of information which do form a kind of mosaic for each of them and maybe the very process of documentation will trigger further recall.

Right now I don't have time to start in on the background facts about William that are known with (relative) confidence, but cannot resist this link to a rather surprising (though somewhat indirect) aspect of his Scottish ancestry, very kindly supplied by my fourth cousin Simon Potter. You will probably need to view it at about 400% magnification.

Sunderings

Having travelled by steam train from Seattle to New York, and thence by steamship across the Atlantic, Frances and Walter arrived in Liverpool on 22 Nov 1913 (see passenger list – though Frances' first name is mangled - and summary panel below) after a journey of some 6,000 miles. He was just 9 months old.

| Name: | Walter Waddell |

| Port of Departure: | New York, New York, United States |

| Arrival Date: | 22 Nov 1913 |

| Port of Arrival: | Liverpool, England and Queenstown, Ireland |

| Ports of Voyage: | Fishguard |

| Ship Name: | Caronia |

| Shipping Line: | Cunard Line |

| Official Number: | 120826 |

Having travelled by steamship across the Atlantic, departing from Liverpool on 19 Jun 1915 (see passenger list and summary panel below), and reaching New York some 5 days later, and thence by steam train across America, Frances and Walter arrived back in Seattle after another journey of some 6,000 miles. He was now approaching 2½ years old.

| Name: | Walter Waddell |

| Gender: | Male |

| Age: | 2 |

| Birth Date: | abt 1913 |

| Departure Date: | 19 Jun 1915 |

| Port of Departure: | Liverpool, England |

| Destination Port: | New York, USA |

| Ship Name: | Philadelphia |

| Shipping Line: | American Line |

| Official Number: | 150617 |

| Master: | A Mills |

What on earth had been going on? They'd been away for over 18 months!

Well, the internet isn't the best place for discussing such things, but my mother in her later years once remarked out of the blue that such a trip home, and of such entirely unexpected duration, had been undertaken as [Frances] had wanted to seek medical advice in Edinburgh, as she didn't trust the American doctors in Seattle.

It must, however, at the very least have had an adverse effect on the emotional ties between Walter and his father, Robert, the latter possibly resenting the fact that Walter's arrival had precipitated matters. My Aunt Jane recently recollected that Walter "was always in the firing line" from his father, and this was to lay the foundations for Walter's problematical health ever after.

Reality Check

At some point during this escapist interlude, Aunt Val (Gueritz) convened a family indaba to discuss certain aspects of her sister's situation. According to my Aunt Jane, Hannah's heart was quailing at the thought of the gruelling journey back to Seattle, and the uncertain future that would then lie ahead.

Accordingly, 'Old Grannie', James Waddell's widow, travelled down from Glasgow to join Val, her husband Elton and their children (just John and Lucy at that time), together with Hannah and William, in the picturesque spa town of Malvern. Val was hardly Robert Waddell's greatest enthusiast, but the vote went in his favour.

I'm very grateful to my sister Anne Marie for providing copies of the following family photographs of William, Val and Elton that were taken at the time, plus a studio photograph saying 'Malvern' on the back:

The architecturally undistinguished residential backdrop does establish commonality of setting but the pictures would be better without most of it:

And there are a few pictures (also from my sister Anne Marie) taken during the extended UK visit but at (I think) a different location – one of him with (possibly) Hannah, another with an old lady called Bonnie (I'm very grateful to my cousin James for this one), and another studio portrait taken when he was noticeably older:

Education

Up to the age of about 11, when he was sent to Chesterfield Grammar School, Walter would go each weekday (possibly with his brother Robin) to the Goodwin's house next door to share home tuition with their daughter Nancy. She often used to remark years later how clever Walter had been and what great things had been expected of him.

I don't remember him ever mentioning this, or the two years or so that he spent at the Grammar School (according to my Aunt Jane). But at the age of 12 or so, the time had come to be brave, as the French executioners used to tell their hapless victims: public school loomed up.

The idea had been (according to my mother not long before she died) that he should be sent to Stowe, the humane and academically nurturing school that had been established two or three years previously and would have been ideal for Walter (as it was for his cousin Jock). But then his father Robert changed his mind. For reasons of economy, or perhaps the undue influence of his colleague Harry Brearley who had little or no formal education and was hostile to 'book learning', he decided instead upon Rossall1, 2, near Fleetwood in Lancashire. William joined in Sep 1925, aged 12½, first in the Preparatory School, and thereafter in Mitre House.

Mitre House (date unknown)

The ethos of Rossall nowadays is clearly very different from its mission then, which was to toughen and desensitise their pupils to prepare them for the gruelling business of Empire. Walter loathed sport of every description, the relentless cadet drills, the disciplinary system, and the antiquated sadism (at least, as he saw it) of the masters.

And the much-vaunted networking opportunities that public schools supposedly provided were of little or no use to him in later life – he once remarked that the most dramatically savage beating that he ever overheard – in fact the whole school heard it – was administered to Derek Walker-Smith, who duly became a Tory political grandee – rather remote from Walter's career path. He was an exact contemporary of Patrick Campbell, a gentle humorist and television panel-game personality who went on record in his autobiography as having loathed Rossall (whence his legendary stutter).

On the lighter side, there was also a boy called Wivell, a fine old surname, who palliated the rigours of school life via a perpetual daydream in which he would speculate, as indeed Archimedes had done similarly before him, as to how many grains of sand there were on Fleetwood beach, or what total volume of ink there might be in all the inkwells of Big School. These speculations were known collectively as Wivell's Wonders, a phrase my brother Simon will well remember hearing tell of.

And even the most dismal schooldays are sometimes enlivened by an episode of unexpected hilarity, if only for the onlookers. One particular incident was recalled many years later by Patrick Campbell, and amongst the classmates who witnessed his ordeal would assuredly have been William himself. But what Campbell scarcely acknowledges is that his ventriloquistic venture was quite possibly an attempt to ward off the approaching stutter that his time at Rossall was to set in [c - c - ]concrete.

Walter left Rossall in 1929, aged 16½, without any academic qualifications whatsoever, and having endured emotional trauma that left its mark on him for life. In the words of my Aunt Jane, he never fully recovered from his time at Rossall (paradoxically, he would have very much admired the Rossall of today, the coeducational aspects in particular!).

But at some point in the years that followed he acquired an all-consuming passion for history, and indulged it to the full for the rest of his life, reading voraciously and gradually integrating it all into a highly idiosyncratic weltanschauung, which he could never resist sharing with the rest of the world, often on social occasions at which a detailed exposition of Marlborough's campaigns against the armies of Louis XIV, or Wellington's tactics during the Peninsular War, or the downfall of the Ottoman Empire, or the finer points of the Balfour Declaration, was not always entirely appreciated by all concerned. And at home these could last until 3 am, as he was a chronic insomniac, and I needed to be up at 7 am to get to school!

And although certainly not religious in the ordinary way, as will be discussed elsewhere, he had an almost obsessive interest in the Manicheans, Cathars and Bogomils – Stephen Runciman's The Mediaeval Manichee would probably have given Winston Churchill's Life of Marlborough a hard run for its money had William been asked by Roy Plomley what book he would take to his Desert Island.

At some point in about 1950 he decided to study for an external degree from the University of London. I really don't know whether this was by direct correspondence course, or by means of evening classes at the local technical college. And I'm not sure what the subject matter was either – it certainly wasn't history, as I do recall that a module in statistics was required – perhaps it was economics, as he was yearning to break into the higher ranks of management by this stage of his career. He would arrive home late from work and disappear into his study for hours of diligent homework – I was given a glimpse of his notes from time to time – meticulously formatted with all sorts of colour coding and bullet-pointing. But he didn't pass the final exam (in about 1953), or the resit which was allowed – inexplicably he'd muffed it. His native resilience soon overcame the inevitable disappointment, however, and he resolved upon a completely new career direction...

Apprenticeship

Apart from a few, well-worn, vignettes of isolated episodes of his working life, William actually revealed very little anecdotally and there seems to be little if any documentary evidence for how he earned a living prior to the 1950's. But first of all, of course, he had to acquire some employable skills.

After he left school, he became apprenticed to Ruston & Hornsby (click here also) (a then recent amalgamation between Rustons of Lincoln and Hornsby of Grantham), a renowned manufacturing company based in Lincoln, producing all manner of heavy engineering products: steam locomotives, diesel locomotives, traction engines, steam engines, diesel engines, gas turbines, motor cars etc etc etc. During the First World War Rustons had also built tanks and Sopwith aircraft. To get some idea of the enormous diversity of their products, browse through the following links to this most fascinating website (to view a backup if a link is broken click there):

- www.oldengine.org/members/ruston/front.htm (or here)

- www.oldengine.org/members/ruston/history1.htm (or here)

- www.oldengine.org/members/ruston/history2.htm (or here)

- www.oldengine.org/members/ruston/history3.htm (or here)

- www.oldengine.org/members/ruston/history4.htm (or here)

- www.oldengine.org/members/ruston/history5.htm (or here)

- www.oldengine.org/members/ruston/history6.htm (or here)

I can't resist a picture of this Ruston roadster

His fellow apprentices probably thought he was a bit of an oddball, especially for his reluctance to join in clogging contests, in which two of the lads, each wearing heavy boots with toe-protectors would face each other and take turns to kick each other on the shin, with increasing severity as the contest progressed. The loser was the first one to back down.

This aside, William found his metier. His aptitude for mechanical things was soon noticed, and he was assigned the role of support engineer for displays of steam traction engines at agricultural shows around the countryside.

Machines of this kind were still widely used for powering agricultural equipment, and in many instances would be shared cooperatively between neighbouring farms.

Perhaps it was during this era that he sported his motor bike, in an era of empty roads and cheap petrol. But I clearly recollect hearing how, one fine or maybe wet day, it skidded off the road into a ditch, wheels spinning and him underneath, and a reluctant resolution on his part not to mess with two-wheel transport again. (I had an analogous epiphany about skiing, many years later.)

Until quite recently (May 2013) I really didn't know how long he stayed with Ruston and Hornsby, though I imagined that with such a vast range of products and technologies to learn about he would have taken what opportunities he could to move around within the different divisions of the company. Supposing he had left school in 1929, and served a full apprenticeship of seven years, he would have been a fully-fledged mechanical engineer by about 1935 or so … which fits very neatly with the known dates of his next enterprise …

According to my Aunt Jane, Ruston & Hornsby now offered him a year's secondment as support engineer to tend some heavy-duty equipment that they had just sold to a corporate client out in Trinidad. I'm sure he took this opportunity avidly, not only to see more of the world but also to assess the job market outside the UK, still barely emerging from the Depression. As it turned out, he did return to Ruston & Hornsby at the end of his Caribbean tour of duty, and remained with them, probably as a technical 'backroom boy' for the remainder of the 1930's and throughout the Second World War.

Trinidad

William would from time to time refer to a semi-mythical interlude spent in Trinidad before the war as a young support engineer working for a company (unspecified, but U Sandy once suggested it was the Acme Petroleum Co.) that extracted asphalt from the extraordinary 95 acre La Brea Tar Lake.

Click here also for some absolutely extraordinary pictures, of which the following give a brief overview:

One thing he mentioned was that the pitch was so hot that it flowed like a liquid and could be pumped to the extraction plant through pipelines, of sufficiently large diameter that the labourers used them as walkways despite their bare feet and the near-scalding temperature of the pipes themselves.

Another recollection, that came up regularly, especially after he took over the running of our household, was that he shared bungalow accommodation with several other young engineers, who took it in turn to cook – the rule being that anyone who complained about the quality of the food served up had immediately to take over the cooking himself. This of course didn't encourage any attempts at haute cuisine, and the food would become progressively direr... on one occasion the chef du jour had in desperation served up something so disgusting that somebody exclaimed "This tastes absolutely awful!", but recovered his presence of mind in the nick of time to add "But, mark you, perfectly cooked!"

He set off to Trinidad on 25 Jan 1936 (see passenger list and summary panel below), three weeks before his 23rd birthday, declaring as per the passenger list his intention to reside there permanently.

| Name: | Wardlaw W Waddell |

| Gender: | Male |

| Age: | 26 |

| Birth Date: | abt 1910 |

| Departure Date: | 25 Jan 1936 |

| Port of Departure: | Dover, England |

| Destination Port: | Trinidad |

| Ship Name: | Crijnssen |

| Shipping Line: | Royal Netherlands Steamship Company |

| Master: | Van Der Graaf |

but returned a year later (see passenger list and summary panel below) – perhaps it was the only way he could escape from cooking duty.

| Name: | Wardlaw W Waddell |

| Birth Date: | abt 1913 |

| Age: | 24 |

| Port of Departure: | Port Limón, Costa Rica |

| Arrival Date: | 19 Jan 1937 |

| Port of Arrival: | Plymouth, England |

| Ports of Voyage: | Dover |

| Ship Name: | Venezuela |

| Shipping Line: | Royal Netherlands Steamship Company |

| Official Number: | 926 |

I'm very grateful to my cousin Simon Potter for finding and supplying these dates and details.

Centurion Tank

At the age of about 6 or 7, I asked him the Question Every Father Dreads – "What did you do during the war, Daddy". And he said, without hesitation, "I lived in a little caravan and I designed the tracks for the Centurion tank".

[Centurion tank, Bovington Tank Museum]

Wow! Well, I now know (via Google) that the Centurion's inception was in 1943. But on what had William been working prior to that to be selected for such a prestigious task? Everybody involved with the Centurion knew that, despite a few compromises in the design phase, the Centurion was going to be the most sensationally effective tank that Britain had ever produced.

The design (Dec 1943 onwards) of the Valiant tank had certainly been bounced on to Ruston & Hornsby (after being fumbled by Vickers and BRC&W), and they had then undertaken manufacture of what was later dubbed the worst British tank of WW2, and never went into full production.

So even if he'd had any personal involvement with the design of this complete turkey, William certainly wouldn't have cared to admit to it.

Ruston and Hornsby also manufactured the MkII Matilda tank, as did a number of other manufacturers, from quite early on in WW2, but hadn't been involved in the design process. So no design opportunity there for William.

It is of course quite conceivable that William had been closely involved as a production engineer during the manufacture of both the Matilda and the Valiant, though it's too late to ask now.

But the biggest puzzle of all is that the Centurion was designed by AEC and manufactured by Leyland Motors, the Royal Ordnance Factories and Vickers. And I can't divine any connection whatsoever with Ruston and Hornsby. And although I don't suspect him of an outright untruth, there is evidently more in this than meets the eye.

I have now (Sep 2019) found a persuasive connection.

Masterbuilder

During my early childhood in the late 1940's one of my very favourite activities was making things from the contents of a large, battered, wooden box of beautifully designed, brightly spray-painted, ingeniously interconnecting, and satisfyingly sturdy metal components of a recreational construction product called Masterbuilder. It was like Meccano, but very much better – not just my opinion, as there was a letter in The Times some years ago (I never thought to keep the cutting) to exactly the same effect, during a correspondence about the declining interest in engineering as a career and what could be done to encourage enthusiasm for it during childhood.

From time to time, my mother would magic up a fresh pack of components, nicely boxed and presented, but she would confiscate the packaging and privily dispose of it. Why?

Another obsession was drawing imaginary castles, ships or aeroplanes, and there seemed to be a conveniently endless supply of office stationery for this purpose – all impressively headed with the title APTITUDE TOYS (based in Loughborough, also makers of Masterbuilder etc etc) and the names of the company directors: W W WADDELL and A W WADDELL. With hindsight of course, these were my father and my Uncle Sandy, partners in this very enterprising joint venture. But before handing this paper over to me my mother would carefully remove the printed headings from each and every page, and dispose of them. Again, why?

I never asked, and neither parent ever elaborated on this, but it's now perfectly obvious that William and Sandy had seen the opportunity to utilise the productive capacity of some local engineering company looking for new work after the outbreak of peace. They'd identified a promising niche in the market for educational toys, and gone into business together. But whether over-optimistic, or under-financed, the enterprise had eventually run into cash-flow problems and had gone into liquidation.

Perhaps William in particular, who should have had the better grasp of life on the Home Front (Sandy had been conscripted into the Army and had been abroad for most of the war) had overestimated the average family's likely discretional spending on children's toys and underestimated the established dominance of Meccano (but in fact, it wasn't until the mid 1950's that Meccano production returned to prewar levels, and so William's battle plan was in that respect entire jusifiable).

But why should anybody be ashamed of an imaginative, ambitious, even though unsuccessful, business venture?

I think his family rather demonised William for having, as they viewed it, lured Sandy into a thoroughly unwise and ill-judged course of action, relieving him of a reputedly large part of his demob gratuity as capital. It's impossible to pass judgement at this remove in time, but Sandy and William remained on perfectly good terms thereafter, and when William died over thirty years later Sandy insisted on paying most of the funeral expenses – he for one certainly bore no such grudge whatever.

The parent company was called KW Products (evidently named for William's then wife, Kathleen Waddell), of which Masterbuilder and Aptitude Toys were brand names. I'm not sure that Aptitude Toys ever materialised into actual products, but Masterbuilder certainly did, of course, and was manufactured at the Erektor Works in Mountsorrel, not far from Quorn (where the family lived at 55 Chaveney Road in 1945/46) and Loughborough (where we lived at 8 Benscliffe Drive in 1946/50).

Reproduced from www.nzmeccano.com/image-49130

(click here for screen-print, or here.)

Masterbuilder

This system was advertised from 1946 until the early 50s. It initially came in four outfits numbered 0 to 4. These had nickelled steel strips and girders and brass wheels and connectors. A unique feature was that there were also bakelite rectangular and circular plates. By about mid 1947 the steel parts became blackened rather than nickelled. In 1949 the system was completely revised with 10 outfits graced with daft names (see last picture for details). The bakelite plates were replaced by flexible steel ones and all main parts were painted red, orange, blue, yellow or grey in a seemingly random manner. A full history can be found in the wonderful "Other Systems Newsletter", No.38, pp 113[5]-113[6]. Details here: ornaverum.org/family/waddell-walter-wardlaw/osn.html

To view some surviving examples of Masterbuilder, as reproduced from the nzmeccano website, click here.

In the truly remarkable website www.osnl.co.uk/ mentioned in the box above can be found a treasure chest, a cornucopia, of extraordinarily detailed technical information, diagrams and full-colour photographs of every single construction system for children, or indeed adults, ever marketed in any country of the world. Excuse my hyperbole, but I was knocked bandy-legged by it all.

It is based around OSN Newsletters posted, or nowadays emailed, to enthusiasts in all corners of the globe. And back-issues are available – I've just received a hardcopy printout of the OSN #38 issue already mentioned, and the webmaster has also very kindly emailed me scanned pages of various other items concerning Masterbuilder in earlier issues of the OSN newsletter. Click here to see all these various items.

I must admit, though, to having been an avid reader of the Meccano Magazine in my Kingsmoor years (ca 1952-1954). By that time I’d outgrown constructional kits, and what really fascinated me was the RAF’s formidable armoury of jet fighters and V-bombers, as documented monthly in MM.

This dovetailed neatly with Frank Hampson’s brilliant cut-away centrefolds in my favourite comic Eagle, of the American and British warplanes involved in the Korean war of that period, and of course the constant threat of Soviet invasion of Western Europe, against which only America and Britain stood firm. For some reason (perhaps her sheer beauty), the English Electric Canberra was particularly memorable.

From my earliest recollections of personal awareness, until the all-too-brief Gorbachev and Yeltsin years, the threat from Russia was a constant daily gastric ulcer. And then, single-handedly, Putin resuscitated it and we have to live with it again. But this time, America no longer seems to care, and to be honest I can’t blame them. As in 1939, Britain and Poland are the only thin red line.

The Day Jobs

Budding stand-up comedians are always advised by their agent (or their parents) "Not to give up on the day job". And it seems to me in retrospect that William probably likewise hedged his bets by moonlighting for Masterbuilder whilst grafting at a conventional employment by day. I certainly don't remember him as being at home much during my first five years or so – he was working day and night to keep the home fires burning.

So, who was he working for?

The Brush Group

Because I can remember the name of this organisation from earliest childhood, it's pretty likely that he first worked for one of the group of Brush companies based in Loughborough. As their Wikipedia articles (click here and here) reveal, the product range and corporate complexity of this group were – and remain – quite staggering. Brush Electrical come particularly to mind, which is hard to square with his very limited electrical expertise. But of course every engineering discipline needs supporting know-how and it's totally plausible that this is what he provided as a very experienced mechanical engineer.

The National Gas and Oil Engine Company

In 1949, this venerable company, based in Ashton-under-Lyne, became associated with the Brush Group. And it was at about that time that William started working away from home, in Ashton under Lyne, with the National Gas and Oil Engine Company. So it is plausible that he had been working with the Brush Group and then transferred up to Ashton-under-Lyne to work on some joint venture with 'the National' as it was called by the locals (click here for their reminiscences).

My mother, with myself and brother, moved up to rejoin him in early 1950, and we lived in a house on the Mottram side of Stalybridge ('Quarry Hill', Mottram Road, Stalybridge, Cheshire, England, …, The Universe, as it says on a schoolbook surviving from that time) just opposite the 'Hare and Hounds' pub, and Stalybridge Celtic football ground, both of which are still there. Thus began the most idyllic period of my life, at least in retrospect – an arcadian time in which I could roam far and wide across apparently illimitable countryside and then be back in time for tea.

Returning to earth, it certainly ties-in with evidence from the previous section that Masterbuilder ceased production, and KW Products ceased trading, at around this time.

The Consultancy Lark

I think it must have been in mid-1954 that we moved south from Stalybridge. My mother (Katie), brother (Simon) and I went to live with Grannie Waddell (at Elm Lodge, Apuldram Lane, in Fishbourne, a mile or so outside Chichester). And William moved into a service flat (a sort of bachelor apartment with room service) on the second floor of 42 Upper Brook Street, just off Park Lane, in the Mayfair district of London.

He had got a job as Industrial Adviser at a rather slick American corporate consultancy named for its chief executive Mead Carney. It is quite possible that it later metamorphosed into the Mead Carney Art Advisory service that you can now find on the internet and would quite possibly consult if you're stratospherically rich and would like to invest in the international art market.

William's job title would nowadays be called Management Consultant. The only client whose name I can remember was Trubenized, a company that had invented a clever way of making mens' shirt collars, and maybe manufactured collars itself, or maybe leased out the technique to other shirt manufacturers in return for royalties, or maybe both. The only internet reference I can find relates to a judgment by the Supreme Court of Canada on 29 Jun 1943 in an action between the Trubenizing Process Corporation and the John Forsyth Co in connection with royalties owed by the latter.

Another client was an Italian manufacturer of women's underwear, based in Milan. It was a pretty major consultancy as he actually took up residence there for a period of about 18 months. The Italian economy was booming, at least in the north, there was plenty of money and fun to be had, and I rather suspect William enjoyed the Dolce Vita to the full.

The consultancy would have involved time and motion studies of the manufacturing processes and plant layout, to improve working efficiency, and analysis of bottlenecks in throughput from raw materials to finished products. One souvenir he did bring home on one of his trips back to England was a larger-than-lifesize iron breast, nipple upwards, which he used as a doorstop, much to the disgust of Katie!

But at some point his relationship with Mr Carney really did go t*ts up, and William either resigned or was sacked. He felt he had been cheated in the severance arrangements, and his final month's salary was never paid. He was pretty caustic about US business ethics ever after.

The job had lasted about three years in total, as in 1957 Katie drove all the way from London to Milan in her ultrasmart two-tone blue and white Hillman Californian (ULK 543), with her brother-in-law Eric Cornes riding shotgun, to collect William and return to England together. Eric, his job done, returned to England by air.

William had also bought a car for himself. His only previous car had been a rather unprepossessing Ford Anglia (the cheapest on the market at £309 in 1949) that he'd briefly owned when we lived in Loughborough. But this one was definitely a Statement. I overheard him justifying to Katie his intended acquisition. "You can't turn up at a client's office in an economy car" he said confidently, "They're going to say "If he can't make money for himself he won't make money for us!"

So he went ahead and acquired his dream car, a Lagonda DB3 saloon (RYK 149). With sleek grey aluminium body, dark red leather upholstery and polished walnut dashboard it did indeed say Success! But I now suspect that it should have said Legacy! as it was not long after Aunt Molly had died …

Furthermore, at the annual Motor Show in Earl's Court later that year, the price had been dropped from £4,000 to £2,000. An avid reader of the Daily Telegraph, I pointed this out to William, who went very quiet for a moment and then said, "There's no need to mention that to Mummy". And I didn't.

The Lagonda certainly was a sumptuous motor, and must indeed have wowed the clients. But it did have drawbacks.

- The aluminium bodywork was very easily dented. And inevitably on its very first outing in London, a bollard jumped out at it and left a massive indentation.

- The engine was designed for high-octane (5-star) petrol – not widely available, especially abroad – and if run on 4-star petrol it would 'pink' like mad when accelerated

- The chassis had four built-in hydraulic jacks, independently operated, to facilitate tyre-changing. But on bad roads they were vulnerable to damage, which compromised the entire hydraulic system. (And that's exactly what happened on holiday in Yugoslavia where the local garage mechanics had never seen anything so complicated before.)

Intermezzo

Memory doesn't just happen; you have to work at it.

Of course all we veterans of the IT industry are painfully aware of those colleagues at the deep blue end of the Asperger scale blessed with total recall of their entire lives and every single corporate computer system they've ever worked with, who would trot it all out at the drop of a hat. Even if you kept soap flakes in the drawer of your desk to feign an attack of rabies or epilepsy, they would wait calmly until you had finished, and then start all over again.

But the rest of us have to try and reconstruct coherent narrative from a random cloud of fragmentary scenes, not date-stamped in any way, and to hopefully reconcile apparent contradictions by resequencing the fragments. And there is an emotional flavour attached to these wisps which is frequently stronger than the visual image itself. Sometime just an aroma – for me, the smell of tractor diesel is immensely evocative, as is the sulphurous reek of 'town gas', or the manly fragrance of one particular aftershave lotion, but there is no image. Our daughter Andrea would surely have observed that Proust took six or seven volumes to sort out his own temps perdu on such a basis but I'll be a lot brisker than that.

Things happened and people came and went, but there was only a fitful association of events and people. In particular, William wove in and out of the narrative, as did Katie, and an assortment of other individuals, some family, some not, would temporarily take their place. And my brother Simon was out of the picture for the whole of this period, during boarding-school term-time at least.

In about August 1955, after the year in Chichester, we moved to a top-floor flat at 25 Cheyne Place, diagonally opposite the Chelsea Physic Garden, and just around the corner from the erstwhile residence of Thomas Carlyle, the justly-titled Sage of Chelsea. There were other distinctions too. In Swan Walk, just opposite, lived Lord and Lady Salisbury (well, the 5th Marquess and Marchioness), he the last outpost of Victorian Toryism and she much given to leaving nasty notes tucked behind the windscreen wipers of Katie's car, saying DO NOT PARK HERE.

And Sir Thomas More, strongly associated with this corner of Chelsea, and whose decorpuscated head is probably buried in Chelsea Old Church nearby, used now and again to glide serenely through my parents' bedroom at night. Or so Katie always insisted. How he got up to the fifth floor, and how his head and body (the latter buried separately at the Tower of London) got together again post mortem, are questions which have only just occurred to me, but which would have been dangerous to ask anyway.

In the spring of 1956 we moved to a ground-floor apartment (No 2) in Basil Mansions§, Basil Street, just a stone's throw from Harrods. And Grandpa and Grandma Blunt moved in with us. His health had declined, and her dementia had progressed, to such an extent that he could no longer cope unaided. They occupied a bed-sitting room just inside the front door, facing onto the street. But later that year he died, and she was immediately relocated to a nursing home in North London. I was taken to see her some years later and she had declined from cosy plumpness to a mere wraith.

But that empty room was to be the beginning of William's final business venture. Not immediately, though, as the last six months or so of his sojourn in Milan had first to be accomplished.

| §: | Retrospectively, after Lord Hume had come to public attention as Foreign Secretary in 1960, or maybe when he became Prime Minister (as Sir Alec Douglas-Home) in 1963, Katie identified him as having from time to time come briskly down the wide marble staircase that surrounded the antiquated liftshaft serving the upper floors of Basil Mansions. And he had four nice-looking daughters, she maintained. I did go so far as to check the electoral register (for the period 1956-58 that she lived there) on ancestry.co.uk, but found no supporting evidence that he too had lived there. But of course as a Peer of the Realm he didn't have a vote, and therefore wouldn't be recorded in the electoral register. And in addition to David, his son and heir, he did have three daughters (Caroline, Meriel and Diana), so quite possibly there was something in what she said. |

Powertyping

William brought back three new enthusiasms on his return from Italy – electric blue business suits, snazzy bowties, and the use of automation to generate top-quality business letters, genuinely but impeccably typed, to attract the attention of the most senior executives in the corporations targeted in a sales campaign by a third-party organisation that either had this capability itself, or had hired a bureau to do it.

This was the beginning of IT-driven direct mail in the UK, and William was to become its Charles Babbage. He opened one of the very first, maybe even the first, bureau in Britain with integrated systems capable of producing business letters so good, so personalised, that the recipients would believe that they'd been typed by a top-rate human typist. Their egos, duly massaged by this deception, were therefore softened-up – and more receptive to the sales-patter in the letter itself.

The only difference today is that the private individual has probably become the prime target of personalised direct mail, and that the letters are produced by laser-printers rather than by typewriters.

After the sitting room used by Grandpa and Grandma Blunt fell vacant in early Nov 1956, it was initially used as a rumpus room, and a full-size table-tennis (alias ping-pong or even whiff-whaff) table was installed for the vast sum of £20 from Gorringes. But Simon was too young to play, and William or Katie were always Much Too Busy to even try, so it soon fell into disuse.

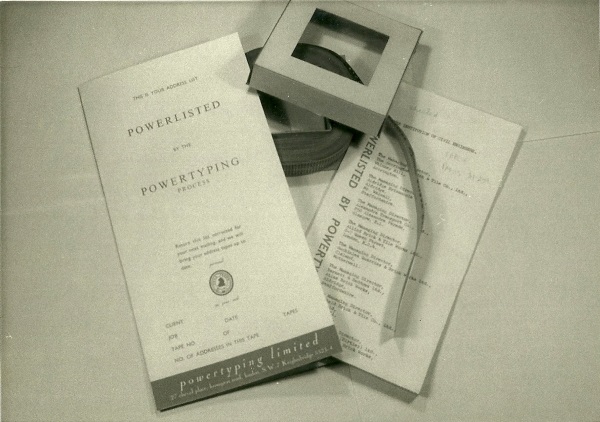

But then, a futuristic contraption (called a Robotyper) and its attendant paraphernalia were smuggled in, and the table-tennis table began a new lease of life as an office work-surface. The Robotyper was the centrepiece of William's new venture alluded to above, which started under the name of Miss Kay Blunt, in an effort to enthuse Katie. William immediately targeted a whole portfolio of senior executives in big business and advertising agencies, using the Robotyper to create a personalised letter to each recipient. It wasn't yet fully automated, as the personalised details had to be typed in manually by a secretary from a list of names, addresses and appropriate salutations. So (after a false start with a one-legged woman called Miss Nosworthy) he engaged a very nice girl, Miss Edwards (I never knew her first name), in her late 20's perhaps, of impeccable family background, to supervise the whole procedure and provide the manual inputs.

And in retrospect I realise that he fell in love with her. And I believe this is what precipitated his divorce proceedings. He already knew from his gumshoe that Katie was spending her afternoons with Captain Peter Court, and it wouldn't be difficult to establish a cast-iron case against her.

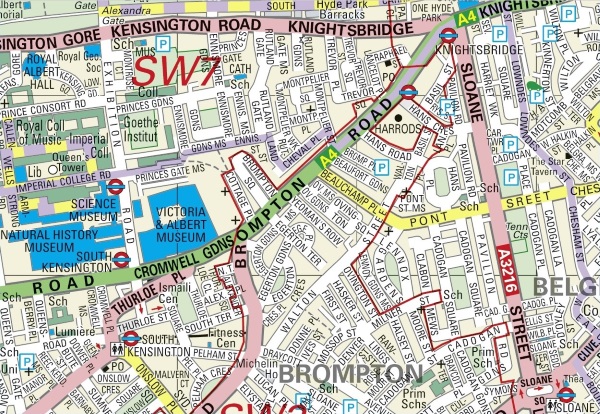

At about the same time (I wasn't taking notes, perhaps it was about mid-1957) he changed the name of the fledgling company to Powertyping, much more macho and businesslike than its rather twee and whimsical predecessor. It was still based in 2 Basil Mansions, though, and despite his discreet investment in soundproof panelling for the walls and ceiling of what had become the office, the burly resident porter Jim, ex sergeant major, a grimly uncompromising Glaswegian, was starting to ask questions about the source of the muffled noise that did seep out. It was of course strictly contrary to the terms of residence to conduct any sort of business on the premises.

So Powertyping had to move, to the first floor of 27 Cheval Place where it stayed until the end of its days. And there was another wrench too: it emerged that Miss Edwards was desperately ill from leukæmia, and soon afterwards she died. I remember sitting for hours in the back of the Lagonda, outside an imposing house surrounded by Surrey woodland, and William then emerging in an evidently distressed state and driving us home in silence.

(Basil Street: see junction of Brompton Road (A4) and Sloane Street (A3216);

Cheval Place: see junction of Brompton Road (A4) and Beauchamp Place)

New premises, new staff and new technology. The new staff were called Janet and Margaret. Janet had a ferocious Essex accent but was absolutely gorgeous – she had a boyfriend, called Trevor, with a motorbike – God how I hated him! Margaret was thin and bitter, and a bit of a trouble-maker. They were both eventually replaced by a super-efficient Queen Bee called Miss Cohen, of whom more later perhaps. William would also make quite extensive use of Simon and myself as slave labour (after school, at weekends and during school holidays), feeding the Robotypers' incessant demands for fresh headed paper.

The new technology was a secondary unit which enabled the personalised details to be entered automatically, obviating the need for operator intervention in that respect, and would support a whole cluster of Robotypers. Cooking with gas!

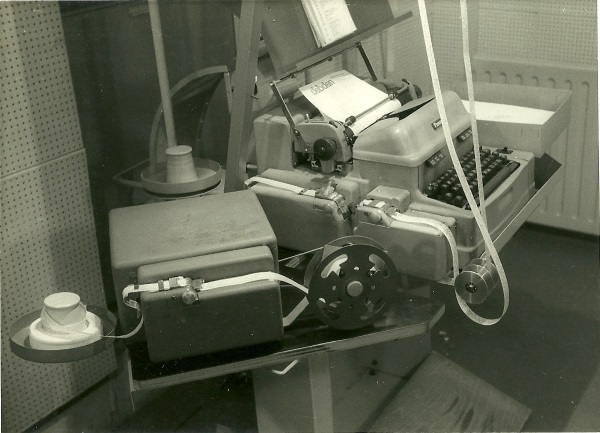

The key feature of the Robotyper was that it operated from 'pianola' rolls, coded perforations in which were read pneumatically and transmitted to the typewriters. Strictly speaking, the Robotyper was the back-end, the typewriter was the front-end, but the two together were loosely described as 'the Robotyper'. I don't pretend to understand the detailed technicalities involved, but click here1, 2 to see some archive material which might make things clearer (unfortunately, the Robotyper doesn't yet feature in Wikipedia).

In due course, Powertyping moved to Flexowriters1, 2, 3 which embodied a newer and more mainstream technology, 7 or 9-track paper tape (I can't remember which), as was then used by the newfangled computers of that era. Tape was a whole lot easier logistically and manipulatively than paper rolls, though I'm not sure how the coded punch-holes were detected by the tape-readers. Strictly speaking, the Flexowriter was the back-end, the typewriter was the front-end, but the two together were loosely described as 'the Flexowriter'. Once again, I don't pretend to understand the detailed technicalities involved, but click here to see some (rather scanty) archive material which might make things clearer (but you'd do better to access the Wikipedia article referenced earlier).

Click here for an affectionate reminiscence of both Robotypers and Flexowriters, as used in the US Senate and White House, in much the same era as their deployment at Powertyping.

Pictured above is one of the Powertyping Flexowriters in action – the repetitive section(s) of each letter are controlled by the continuous loop(s) seen on the RHS, while the personalised content is fed from the spool on the LHS. Note the ubiquitous sound-proofing panels in the background – no longer essential for secrecy but vitally important to protect the operators' hearing and sanity: the Robotypers and Flexowriters were incredibly noisy.

To further streamline the business, William took on a Hillman delivery van, NML 54, and a driver, Len, a quiet semi-retired bulbously-nosed Fulham supporter, always clad in a brown warehouseman's coat, who collected company stationery from the clients, and took the typed, signed, folded, sealed and franked daily output to the post office.

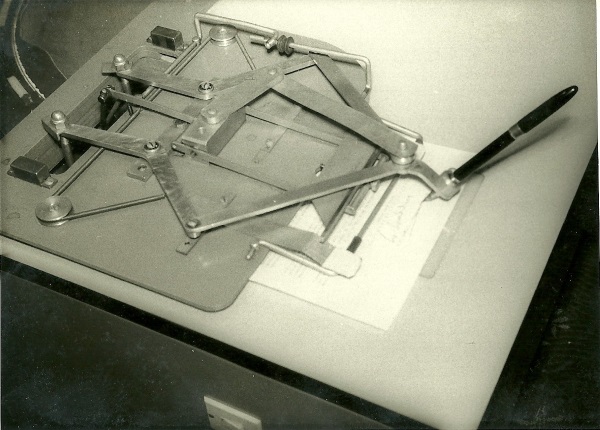

Yes, signed! William had acquired an Autopen, which saved the nominal signatory the burden of signing maybe hundreds or thousands of letters by hand. The photograph below, not terribly well-focussed, shows the Autopen in the the process of signing his own very distinctive signature. In the top LH corner you can see part of the template whose perimeter encodes the (x,y) wiggles of that particular signature. This particular model was made in France, I think he said, although the very first such device was made and patented by an Englishman in 1804!

And around this time, about 1959/60, he also acquired a "folder, stuffer and sealer" of which I don't have a photograph, which did pretty well what it said on the tin, an order of magnitude faster than would be humanly possible. Pictured below is a modern equivalent.

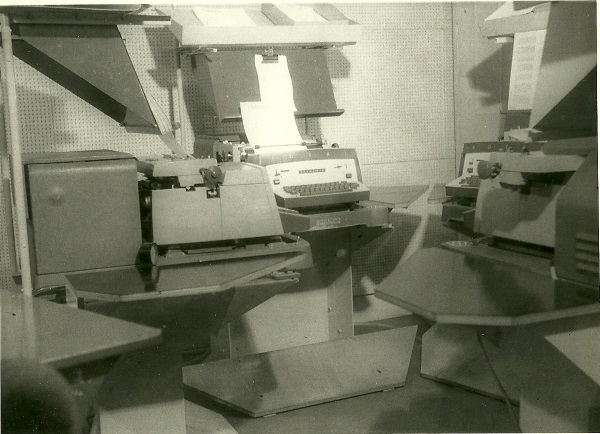

However, clouds were looming – he'd pretty well exhausted the capital provided by Great Aunt Molly's legacy, and IBM typewriters were expensive machines to maintain and replace (or lease). So he began to experiment with alternative, cheaper, typewriters. Maybe that's the explanation for the photograph below – these Royal machines seem to be producing, or updating, fanfold name-and-address lists as an auxiliary service.

As witness this next photograph.

By late 1960 he decided to sublet 2 Basil Mansions and move out to a much smaller flat in a newly built apartment block in Kersfield Road, near the top of Putney Hill. And he borrowed a considerable sum from his mother (the cause of endless subsequent recriminations from the rest of his family, especially as he bought a yacht the following year!). And I think there was a downturn in business, as there so often seems to be in Britain – one so rarely hears of upturns).

He soldiered on with Powertyping until about the mid-1960's, as the arrival of a Labour government in Oct 1964 had more or less put paid (as he later alleged) to his flow of business. I'd been only intermittently in touch with him since late 1962, and just don't know the gory details.

I got back to the UK just before that General Election and in due course found him in the grip of a new enthusiasm: as per The Wind in the Willows, canary-coloured caravans were out, and powerful motor cars were in, "Poop-poop"! Never one to underestimate his audience's stamina, he would in due course take Sonia Kaulback, as she then was, and Bernice Lewis, her friend and colleague at A Cohen & Co (renowned for metal import/export rather than direct mail), to lunch, in a very kindly and well-meant way, and dazzled them with a 90 minute exposition on the inner workings of automated typewriters and how he was going to revolutionise the whole shebang. They staggered back to work half an hour late, still shell-shocked.

His wizard wheeze related to the perennial problem with client requirements as to the font used by, for example, the IBM typewriters (proportional spacing being their standard, I believe). Fonts had to be consistent with the clients' letter-headings and brochures etc, and this meant unpicking the IBM typewriter from the rest of the Flexowriter (a notoriously difficult business) and substituting an appropriate alternative.

An experienced mechanical engineer, William would have been able to tackle this himself, but his time would be better spent elsewhere, and so a skilled typewriter mechanic would be called in. Such individuals were becoming rarer, and their call-out fees ever greater.

His idea was to create a universal interface between the Flexowriter back-end and any typewriter front-end whatsoever. He had relocated a Flexowriter to my erstwhile bedroom at 41 Kersfield Road, which now became a laboratory cum workshop. A brief account of the events that followed was given at my brother Simon's funeral, as William had shanghaied Simon to devise all the electronics involved. The prototype worked impressively well, and a wealthy entrepreneur was briefly interested in financing its development to market. But the advent of word-processors, computers and (later on) laser printers had signed the death-warrant of electromechanical typewriters.

William's focus on R&D had left his business unattended (his staff were long gone, and he'd been trying to run Powertyping singlehanded) and now his new technology was already out of date. There was an eerie re-run of this situation at my first employers, a software house called CAP, in the late 1970's and early 1980's, whose radical new universal operating system BOS, which when suitably parameterised would interface with any other microcomputer's operating system, arrived just in time to be crushed by the IBM PC and Microsoft's DOS.

Religious Belief

William's mother Hannah was deeply devout, in a quietly undemonstrative Scottish sort of way, and the only open breach of her reserve would be at the closing lines of the Apostles' Creed, concerning the resurrection of the body, and the life everlasting, when she would cross herself with clearly-felt emotion, as I well remember.

His father Robert, on the other hand, was openly unconcerned about such matters, within the family circle at least, and as a professional engineer might well have thought such beliefs to be unrealistic and impractical female stuff. But society as whole was still religiously observant in that era, of course, and it didn't do to express agnosticism, let alone atheism, too publicly.

Having each been choirboys in St George's Chapel at Windsor for several years prior to public school, his brothers Robin and Sandy would have been deeply imbued with the ceremonial and ethos of the Church of England, and Sandy was certainly a staunch Anglican all his long life; Robin's life was cut cruelly short in his early twenties, and he was perhaps the most enigmatic member of the family, so one cannot really say anything for certain.

William's sisters Frances and Jane took somewhat different paths. Frances, I discovered decades down the line, was my godmother though had certainly never followed-up on my spiritual welfare – though what godparent does these days – but converted to Roman Catholicism in her late sixties or early seventies. Jane, on the other hand, used to quiz me on the way home from Matins each Sunday morning, as to the content and meaning of the sermon. Following her move to Canada I'm fairly sure she remained in the mainstream with the Anglican Church of Canada.

But what about William himself?

I can remember just one occasion when he and my mother took me to church, as a small boy, and apart from funerals or weddings I cannot recollect any subsequent occasion whatsoever. There was no reference to, discussion of, or instruction in, such matters within the household, and so neither parent could have been described as anything but areligious.

Presumably, during his childhood, religious issues would have been fraught with interparental tension and he had learned simply to fence the whole thing off in his mind.

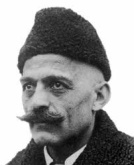

But in early adulthood, he became influenced by the ideas and writings of P D Ouspensky (aka Uspensky), especially as expressed in Ouspensky's book Tertium Organum (Organum implying a logical organisation or system – Aristotle's Organon led the way followed by Francis Bacon's Novum Organum), a copy of which (translated from the original Russian) I well remember from childhood. It did rather intrigue me, but might just as well have remained in Russian for all the sense I could make of it after the first page. William was very taken by the idea of higher dimensions, popular in fashionable circles since Victorian times, but especially espoused by Ouspensky, which held that objects or events (physical or indeed psychic) occurring in this (3D) world were but projections from a higher dimensionality – as for example from the tesseract to the cube. William more than once described to me the idea of a helical tube from a higher dimensionality passing through our (3D) surroundings and causing the illusion of a (3D) sphere revolving in a circular path – precisely as a planet orbits around a central solar focus. It's a neat idea, but the devil is in the details of course – it's hard to represent a trip to the supermarket, for example, as being projected from a higher dimensionality, I'd say.

There was also a strong mystical side to Ouspensky's writings, probably inherited from his longtime discipleship of G I Gurdjieff – I'm really unable to offer any worthwhile opinion on such things: to me The Unknowable is precisely what it says on the tin, and any attempt to speculate about it is pretty pointless. But I think for William this aspect did sow certain seeds that germinated almost half a lifetime later …

And there the matter stood until he reached late middle age, when he became interested – purely on an intellectual level – with firstly the Essenes and Gnosticism generally, and then the whole complex history of Dualism from its earliest Manichean roots in Persia right through to the medieval era of the Cathars, Albigensians and Bogomils. And naturally, at the drop of a hat, or sometimes quite unprompted, he would regale us with his latest researches into these topics – fortunately, my wife was quite interested in these things herself, and so such discourse was less hard going than it might have been.

Also, the natural fascination for the early history of the Free Churches which is hard-wired into the DNA of every Scot, whether lapsed or not, started to assert itself at around the same time, and William became a fount of knowledge on these matters too, especially as his (indirect) ancestors the Erskines had played such a prominent rôle in them. Once again, his interest wasn't theologically driven, as the schisms in question were almost invariably triggered by issues of governance rather than doctrine. As an example of this, you might like to view the following links

- Excerpt from a published History of the Free Churches

- Partial transcript of letter from William about the political context

- Images of the letter itself

Of course, I'm not remotely qualified to assess the historical accuracy of his commentary, but it's a good example of the way his narrative style, verbal or written, ranges from the sonorous to the vernacular, and the vividness of his imagery – as for instance regarding the executions of Archbishop Laud and Sir Thomas Strafford:

"Their heads flew yards before bouncing, but not far enough to pacify the House of Commons"

What could be more expressive and informative?

As God once said, and I think rightly...

Only Field Marshal Montgomery, Monty to the rest of us, could have made that sort of preliminary observation (if indeed he ever did, Wikipedia aren't sure). With just one exception, perhaps two. King Alfonso the Learned of Spain, wont to remark that had he been present at the Creation he would have been able to advise God how to order things better, was the one.

But the other was William. For all the myriad deficiencies in his upbringing and the shortcomings of his education, and despite his undeniably fizzled business ventures and limited conventional career accomplishments, he was invariably possessed of an entirely genuine, slightly blokeish, self-belief – reminiscent of (the fictitious) Henry Root or Alan Partridge, but packaged with an infinite kindliness, tolerance and profound intelligence.

And this was because he was, as the phrase is, comfortable in his own skin. For many generations of Waddells past and present, we have insisted on thinking things out for ourselves, as a much higher priority than conforming to the prevailing career requirements and milestones. So we don't get far, generally, but by golly we dig deep.

In some ways, he was not dissimilar to W S Churchill – or W L Spencer-Churchill if you're finicky – who could easily have qualified for the same sort of epitaph had it not been for the German genius for recurrent loathsomeness.

It would be silly to look for exact parallels – but absolutely predominant was a desire to vindicate themselves to their vanished fathers, coupled with a phenomenal memory and an instinctive voracity for military, constitutional and political history.

But there's absolutely no doubt as to their shared hero:

(Oddly enough, it appears that his father was also a Sir Winston Churchill!)

Marie Hamilton, Her Ballad

After we moved down to London (Cheyne Place, Chelsea, in 1955/56; Basil Street, Knightsbridge, in 1956/61; Kersfield Road, Putney, from 1961 until I left in 1963), Ryland Lamberty and Helen Ferguson became our family GP's. Their practice was in Kentish Town, not easy to reach from any of our various addresses, so often enough any medical check-up or prescription would be attended to during one of our frequent social visits to Wyldes Hollow, Hampstead Way, where they, their son John, and the "dear wee hunchback" Annie the Nannie, of blessed memory, resided.

Another reason for avoiding the surgery was that William drove a very sleek aluminium-bodied Lagonda saloon, an irresistible target for the vandals and car-thieves who frequented the area. Kentish Town was undeniably rough, and many of the patients attending the surgery lived lives beset by poverty, malnutrition, drink, drugs, crime and sexual abuse. Just like East Enders, really. Indeed the third GP in the practice, quite emotionally-fragile himself, eventually got struck-off for his extraordinarily liberal prescription regime of uppers, downers, etc etc.

Sometime in the early 1960s, Ryland got the idea that suitably-disguised narratives of their more eccentric or dysfunctional patients would make very good short-story material (rather like James Herriott and Tricky Woo). He passed one or two of these on to William, who bounced them on to me. I was a voracious reader in those days but to me they didn't seem quite oven-ready, and indeed I don't think the book ever got very far.

But a decade or so later, William showed me a sheaf of typescript and said confidently "Read this, you'll really enjoy it, hot stuff, BBC2 will lap it up" or words to that effect. The first page was embarrassingly steamy, so I flicked through rapidly, mumbled appreciatively and handed it back before the music stopped.

Imagine my astonishment, Gentle Reader, when this self-same TV script resurfaced a couple of months ago (I'm very grateful to my sister Anne Marie for this). It may never reach our TV screens – except in an episode of New Tricks – but it is a fascinating social and personal document in its own right.

- A thinly-disguised narrative of a real (ie 1960's Kentish Town) domestic tragedy involving adultery, murder and infanticide.

- A musical counterpoint of the ancient Scottish lament Marie Hamilton, Her Ballad.

- A subtext of Manichean Dualism and the idealisation of the GP concerned as a Cathar 'Perfecta' (see below).

- A richly-detailed implication that the medical protagonist was Helen Ferguson herself and that the fabulated Marie Hamilton was actually a patient of hers.

It's rather odd that Ryland's surname is repeatedly – and inaccurately – given as Lambert, but maybe that's just a nod in the direction of the Hippocratic tradition of patient non-identifiability. Helen herself had succumbed to cancer seven years earlier, and so was beyond the reach of any inquiry regarding the ethics of her decision …

William had this to say about her TV personification as Dr Catharine Goodason (both forename and surname symbolically chosen, I'd say!):

… Dr Goodason is covertly portrayed as a Cathar 'Perfecta', ordained deaconess. (See Runciman, The Mediaeval Manichee, C U P, 1960). Essentially, Catharism combined most of the points of teaching that so many students and uncommitted people are looking for today. Basically, they considered that this life is Purgatory, that a higher life was attainable, explained the existence of evil and good side by side by Dualism, one Deity who made the good, and another who created the evil. The essential point they stressed being that souls live in Paradise, until called to earthly life to enter the body of a conceived child. Followed to the ultimate conclusion, this involved the belief that the kindest act possible was to leave souls in peace in some sort of heavenly waiting room as long as might be. There was one major practice to commend Catharism to modern thought. They ordained women into their priesthood equally with men. Much of the Cathar viewpoint lingers on in other creeds and in remote corners of Europe. As non-violent, non-resisting total pacifists, they were virtually exterminated by the Inquisition, created for the purpose, as heretics in 1415, with the aid of the Crusaders.

As for the eponymous Marie Hamilton – who was she, and what exactly did she do? The ballad dates from the 16th century, in Scotland of course, but the closest parallel to the actual events took place in the early 18th century in Russia.

Click here if you'd like to access the script.

Health

I'm omitting any mention of the possible shadow cast over the family two generations previously, as discussed in the Ghosts section.

As my Aunt Jane has remarked in various recent (2013) conversations about the relationship between her father, whom she actually very much admired in many ways, and her brother Walter aka William:

- [Robert] detested small children, particularly boys

- [Walter] was always in the firing line

- [Walter's] father hated him so much they couldn't be in the same room together

As already suggested in the Sunderings section, I can only think that this toxic antipathy originated in the lengthy separation that occurred during William's early childhood. He himself was very mild-mannered, rather evasive of emotional confrontation, and certainly not a determined hater.

But he made a number of veiled references in later life to a period of nervous breakdown and psychiatric analysis during his teenage years – possibly after leaving Rossall (which he certainly had hated!). I think the opportunity of a constructive dialogue with a sympathetic adult was an enormous help to William, and he took aboard a rational humanistic world-view which provided a stabilising influence ever after – plus his mentor's enthusiasm for Ousspensky.

At the age of 8, according to Aunt Jane, William accidentally dislodged a large ornamental stone vase from the top step outside the front door and it knocked out six of his front adult teeth. It was not until adulthood, when he could make the arrangements himself, that he acquired dentures to normalise his appearance. The dental technology had certainly existed prior to that, but the parental concern had not.

That was admittedly not such an image-conscious era as ours, but he must still have been serially embarrassed when moving on into adolescence when ones face is ones fortune.

Whether from considerations of domestic economy, or dietary principle (he was a great admirer of that legendary vegetarian George Bernard Shaw, who did admittedly live to a great age in good health), or Puritanism (we remember Macaulay's famous remark about the Puritans' objection to bear-baiting), Robert imposed a strict vegetarian regime upon the entire household.

In that dietarily uninformed era, the essential nutritional requirements for human wellbeing weren't widely understood – in particular, the vital importance of vitamin B12 supplements to compensate for the B12 normally ingested from meat and other animal-based food products. Vitamin B12 deficiency can cause severe and irreversible damage, especially to the brain and nervous system. What subsequent health problems – for the whole family, not just William – might well have had their origins here?

Indeed, Aunt Jane tells of a gnomic remark to William by one of the crustiest masters at Rossall (not then renowned for its empathic staff), "The trouble with you, boy, is that your mother is always ill". And her problems were worsened, so the omniscient Aunt observed (though not directly, being the youngest), when a new addition to the family was on its way, at a time when the maternal reserves are depleted and the metabolic strain is greatest.

From childhood onwards William suffered from asthma, a condition now recognised as being stress-related, of course, and for which there were few if any remedies available in those far-off days.

But, so he once remarked to me, the asthma stopped at once and disappeared for ever the day his father died. A sombre reflection of their relationship, of course, and it certainly shouldn't be taken as an action plan for asthmatics generally.

Another stress-related condition, of course, is migraine (although there are numerous other triggers such a red wine or chocolate, of course). I have never suffered a genuine migraine myself, but I've come to believe that it is also a symptom of inner psychological conflict. Both my parents suffered from it, though in William's case I think the attacks lessened in frequency and intensity as he grew older and the inner conflicts dissolved.

One of the major frissons of childhood was to catch a glimpse of William's post-surgical 'Railway Track', as I thought of it. This was a cheloided scar, about ½ inch wide, that ran from just below the sternum to just above the navel, liberally endowed with tranverse stitch-marks for all the world like railway sleepers, and was exposed to family viewing whenever his pyjama jacket happened to be unbuttoned.

Wow! What was this? Who nowadays has heard of the vagus nerve (and hasn't confused it with the G-spot)?

All we really need to know about the vagus nerve in this connection is that

Besides output to the various organs in the body, the vagus nerve conveys sensory information about the state of the body's organs to the central nervous system. 80-90% of the nerve fibres in the vagus nerve are afferent (sensory) nerves communicating the state of the viscera to the brain.

The other one you'll have to look up for yourself.

The idea was that

Vagotomy was once popular as a way of treating and preventing peptic ulcer disease and subsequent ulcer perforations. It was thought that peptic ulcer disease was due to excess secretion of the acid environment in the stomach, or at least that peptic ulcer disease was made worse by hyperacidity. Vagotomy was a way to reduce the acidity of the stomach, by denervating the parietal cells that produce acid. This was done with the hope that it would treat or prevent peptic ulcers. It also had the effect of reducing or eliminating symptoms of gastroesophageal reflux in those who suffered from it. The incidence of vagotomy decreased following the discovery … that H. pylori is responsible for most peptic ulcers, because H. pylori can be treated much less invasively. One potential side effect of vagotomy is a vitamin B12 deficiency[!].

Slightly less technically put,

The vagus nerves are currently not attracting the attention that they once did. A few decades ago every medical student was taught the indications for vagotomy (usually in combination with partial gastrectomy) in cases of peptic ulcers. The idea was that severing the vagus nerves would decrease acid production and alter peristalsis in the stomach, thereby facilitating healing.This was before the invention of acid-suppressing medication and the discovery of antibiotic-sensitive H. pylori in ulcers. These new treatments have made vagotomy (almost) "history".

The fundamental idea was that extreme emotions such as stress, anxiety, grief or anger are transmitted from the brain down the vagus nerve (as it is deferent as well as afferent) to the (parietal calls in the) stomach, making it start excessive acid-production and thereby initiating or exacerbating peptic ulcers. And for William, somewhere around the early 1950's, the vagotomy was 100% effective.

His next medical crisis, in July 1955, started quite innocuously as acute appendicitis. By this time he was based in London, and so his GP (Ryland Lamberty) arranged for him to be admitted to the Royal Free Hospital for treatment with streptomycin and removal of the offending organ. This was duly actioned, and he kept the evil-looking results in a small jar of fluid (I don't know, alcohol or formaldehyde) in his sock drawer (where he also kept his wallet), to discourage any intrusion.

But whilst still at the Royal Free, recovering from the appendectomy, he succumbed to the last-ever outbreak in Britain of poliomyelitis, or polio for short. From the late 1880's to the mid 1950's it was a global epidemic, though now has been almost totally eliminated through mass vaccination. Viral in origin, and therefore not susceptible to antibiotics, polio caused partial or total paralysis, and disabling limb deformities.

What does its name tell us about it?

- The prefix 'polio' comes from the Greek (polios) for grey.

- The word 'myelin' comes from the Greek (muelos) for marrow, referring to the contents of the spinal cord.

- Myelitis means an inflammation of the myelin sheath protecting nerve fibres. Myelin is an insulating layer that forms around nerve fibres, including those in the brain and spinal cord. It's made up of protein and fatty substances, and is essential for the proper functioning of the nervous system.

- So poliomyelitis means inflammation of the grey matter of the spinal cord. But that's really only half-right at best, because myelinated nervous fibres actually appear white rather than grey. And, as already mentioned, they occur in the brain as well as the spinal cord.

Well, now we know1 what William caught, along with over 300 other people, comprising patients, doctors, nurses and support staff. About 20 years ago, I met a retired nurse, who had been a victim of that outbreak and had walked with a severe limp ever after. William was, apparently, more fortunate and seemed to make a full recovery.

But just a few weeks later, he and I were walking back from the Chichester city-centre towards the little village of Fishbourne where I was living with my grandmother at the time, and had just passed Westgate when he suddenly began to lurch and stagger like a music-hall drunkard. It was very frightening for us both. Fortunately there was a telephone box across the road and he somehow got to it and rang for a taxi home.

Thus began his lifelong battle with vertigo, in all probability caused by either the polio or the streptomycin2, which is now known to have the potential for serious damage to the inner ear. The effects were counteracted to some extent by special glasses developed for him by the opticians Dolland & Aitchison, but he continued to walk like a mildly-sozzled sailor until eventually forced into a wheelchair some 15+ years later.

| 1: | Except that we don't. The true nature of the symptoms, and the cause of that outbreak, and many other equally puzzling outbreaks around the world, has been hotly disputed ever since (the first, semi-official, account of the Royal Free episode tried to blame it on mass hysteria, as most of the victims were women!) and it is now associated with CFS (chronic fatigue syndrome) and ME (myalgic encephalomyelitis), neither of which bear any resemblance to William's case, and are themselves as equally controversial. |

| 2: | Streptomycin, discovered in 1943, was the first antibiotic that could be used to cure tuberculosis. When I, as a child of about 3, contracted a lump on my neck which turned out to be lymphatic TB (the old names for which were scrofula, from the Latin for a brood sow, or the King's Evil), not only was the lump removed by surgery (the anaesthetic, applied by gas-mask, was so administered so lightly that I distinctly remember waking up halfway through), but I was also treated with streptomycin. Whether or not that was the cause of the acute but fortunately intermittent side-effect that I too have had ever since, is of course empty speculation. Anyway, it's a bit late to sue! |

Though no Charles Atlas, William was quite strongly built, but totally unathletic – I don't suppose he'd taken any exercise since leaving school, and was utterly uninterested in sport of any kind. On the other hand, he ate very sparingly, seldom drank so much as a glass of wine, and hadn't smoked "since Stafford Cripps put up the cost of cigarettes in the 1948 budget". I only ever saw him smoke on one occasion, after a particularly bruising marital confrontation and he accepted a cigarette from Ryland Lamberty, our GP, who was talking him back down to earth again.

So really, he should have been quite a healthy person, entitled to expect the Biblical allocation of life-span, expressed in verse 10 of the 90th Psalm:

The days of our years are threescore years and ten,

and if by reason of strength they be fourscore years,

yet is their strength labour and sorrow,

for it is soon cut off, and we fly away.

But the labour and sorrow started soon after he reached just the threescore: a series of increasingly severe strokes cumulatively disabled him over the next five years, confining him to a large and cumbersome wheelchair. He didn't actually seem to mind – he was perfectly happy with a stack of books about the minutiae of eighteenth or nineteenth century European political history, and a captive audience to explain to all about what he'd just been reading.

He died of a sudden heart attack aged just 66.

William's Wit and Wisdom

William left school at the age of about 16 with no qualifications whatsoever (his first wife Katie left at 14 likewise), but at some point – like W S Churchill – he embarked on a lifelong habit of voracious reading. She however, as was said of the Bourbon monarchy, learned nothing (apart from her excellent shorthand and typing) and forgot nothing. That, I think, is one of the many reasons they grew apart after marriage.

He was remarkably tolerant and unprejudiced, even by the standards of this present day, of religion, politics, class, race or colour, and had neither heroes nor anti-heroes, apart possibly from Clemenceau and le Duc de Saint Simon on the one hand and Harold Wilson on the other, actually more of a nemesis, really – "All our troubles at Powertyping," he said bitterly more than once, "began with that man's arrival in office".

Some of his obiter dicta were simply rules of thumb picked up from his father or engineering days, and some were from his own observations along the way. Some were simply vivid turns of phrase rather than apothegms, but all of them defined his unquenchable curiosity and acuteness. His judgements were not infallible, but always pithy and memorable. I don't suppose he ever read a novel in his life, but his father was extremely well read in Scott, Stevenson, Conrad, Kipling, Shaw, and the like, and William's ear was probably tuned to Robert's measured cadences of speech, with a goodly pinch of vulgarisms thrown in for variety.

Robert had once, for example, in a tone of mild reproof, enquired of his wife "Hannah, what is this upon my plate that smells like dead men's underwear?"

The following representatives are listed just as they occurred to me at the time of writing [Feb 2016] – my brother Simon could doubtless have contributed many more.

- "Chief Assistant to the Assistant Chief" [maybe first heard in At the Drop of a Hat but William's phrase for serious career progress, only one leapfrog from being Top Man on the Totem Pole.]

- The wise man goes when he can, the fool when he must [one of Robert Waddell's maxims, repeated by Billy Connolly in the 2013 film Quartet; generalised by Jack Nicholson in the 2007 film The Bucket List, "Never waste an er*ction, never pass up a bathroom, and never trust a f*rt" – but William would never have descended to such blatancy.]

- Bewitched, buggered and bewildered [in a state of helpless confusion; parody of song in 1940 Rodgers and Hart musical Pal Joey.]

- Vee vill der ratschidt mitt der reis gemisch to soot der kustomer [said sotto voce when going the extra mile for a Powertyping client; garbled quotation.]

- Bigger cheeses for pregnant mice [his parody of a populist slogan or electoral promise].

- Upside down sixty feet above the runway and climbing fast [in a bad situation that's rapidly getting worse.]

- Any damned fool can be uncomfortable.

- He travels the fastest who travels alone (Down to Gehenna or up to the Throne / He travels the fastest who travels alone: Kipling).

- If you put chemistry through a sieve, what's left is physics [said to me in 1953; uncannily perceptive for somebody who had little formal education in either subject, and had never heard of Dirac (who said the same thing in many more words).]

- It's bums not bags as books seats in Bradford [a restatement of the ancient proverb "When in Rome etc" - always conform with local customs and culture.]

- Aru bingsto neforas ses [an inscription he found neatly engraved on a well-worn stone pillar in the hillside woodland across the Mottram Road in the early 1950's. Click here

if you're baffled.]X

A rub(b)ing stone for asses

- When a dictatorship gets into trouble economically or politically, it starts a foreign war in order that the populace rally round in fervent support of the Mother Country [current examples (Feb 2016) being Russia, China and North Korea, needless to say.]

- Dictators are invariably surrounded by mediocrities, as anyone suspected of talent is immediately eliminated as being a potential rival [I'm reminded of the famous Spitting Image 'Vegetables' sketch.]

- Whatever its speed, a rolling object can't surmount a barrier more than one third its height.

- Not a girl in the house ready, and the street full of sailors.

- Standing around like a f*rt in a trance.

- As much use as a f*rt in a colander [or thunderstorm].

- The Turkey Trots or Prussian Two-Step [his euphemism for the Wherry-Go-Nimbles]

- A face like three kicks in a clay wall [of some unprepossessingly lardy person].

- The only country to have gone straight from barbarism to decadence without an intervening period of civilisation [Clemenceau on USA].

- Straight out of trees into Cadillacs [Venezuelan taxi-drivers].

- The feudal system is the only one that ever really worked.

- Art is a coded message from the artist's subconscious to yours, and if your code is different you just won't understand what he's saying.

- Hitler never wanted war with Britain [also propounded by the historian and TV talking head A J P Taylor, whom William greatly admired].

- The fallacy of the Marxist "value of something resides in the time expended on it" theory lies in the broken dam.

- A good driver never uses his brakes, he uses his engine to slow down, except in emergency [my brother Simon said the opposite, "B*gger the brakes, save the engine". I'm happy for them to sort it out.].