Was H G Wells the first to think of the atom bomb?

4 July 2015

The atom bomb was one of the defining inventions of the 20th Century. So how did science fiction writer H G Wells predict its invention three decades before the first detonations, asks Samira Ahmed.

Imagine you're the greatest fantasy writer of your age. One day you dream up the idea of a bomb of infinite power. You call it the "atomic bomb".

H G Wells first imagined a uranium-based hand grenade that "would continue to explode indefinitely" in his 1914 novel The World Set Free.

He even thought it would be dropped from planes. What he couldn't predict was how a strange conjunction of his friends and acquaintances – notably Winston Churchill, who'd read all Wells's novels twice, and the physicist Leo Szilard – would turn the idea from fantasy to reality, leaving them deeply tormented by the scale of destructive power that it unleashed.

The story of the atom bomb starts in the Edwardian age, when scientists such as Ernest Rutherford were grappling with a new way of conceiving the physical world.

The idea was that solid elements might be made up of tiny particles in atoms. "When it became apparent that the Rutherford atom had a dense nucleus, there was a sense that it was like a coiled spring," says Andrew Nahum, curator of the Science Museum's Churchill's Scientists exhibition.

H G Wells in 1944

Wells was fascinated with the new discoveries. He had a track record of predicting technological innovations. Winston Churchill credited Wells for coming up with the idea of using aeroplanes and tanks in combat ahead of World War One.

The two men met and discussed ideas over the decades, especially as Churchill, a highly popular writer himself, spent the interwar years out of political power, contemplating the rising instability of Europe.

Churchill grasped the danger of technology running ahead of human maturity, penning a 1924 article in the Pall Mall Gazette called "Shall we all commit suicide?". In the article, Churchill wrote: "Might a bomb no bigger than an orange be found to possess a secret power to destroy a whole block of buildings – nay to concentrate the force of a thousand tons of cordite and blast a township at a stroke?"

This idea of the orange-sized bomb is credited by Graham Farmelo, author of Churchill's Bomb, directly to the imagery of The World Set Free.

By 1932 British scientists had succeeded in splitting the atom for the first time by artificial means, although some believed it couldn't produce huge amounts of energy.

But the same year the Hungarian emigre physicist Leo Szilard read The World Set Free. Szilard believed that the splitting of the atom could produce vast energy. He later wrote that Wells showed him "what the liberation of atomic energy on a large scale would mean".

Szilard suddenly came up with the answer in September 1933 – the chain reaction – while watching the traffic lights turn green in Russell Square in London. He wrote: "It suddenly occurred to me that if we could find an element which is split by neutrons and which would emit two neutrons when it absorbed one neutron, such an element, if assembled in sufficiently large mass, could sustain a nuclear chain reaction."

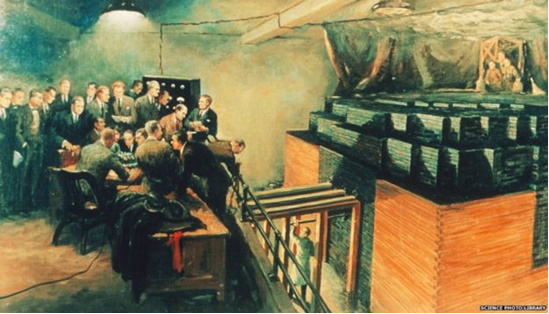

Fustration of the first self-sustaining nuclear chain reaction

In that eureka moment, Szilard also felt great fear – of how a bustling city like London and all its inhabitants could be destroyed in an instant as he reflected in his memoir published in 1968: "Knowing what it would mean – and I knew because I had read H G Wells – I did not want this patent to become public."

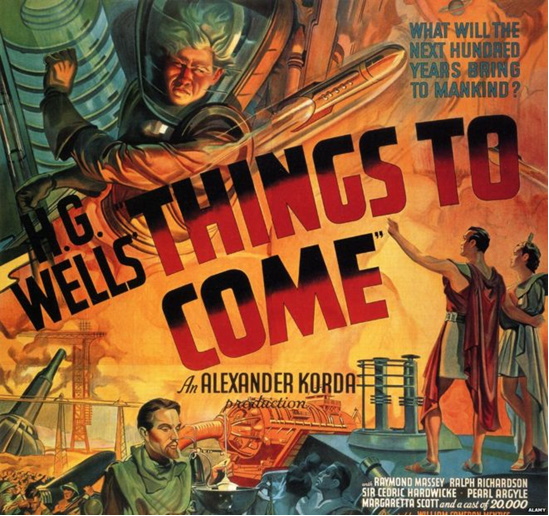

The Nazis were on the rise and Szilard was deeply anxious about who else might be working on the chain reaction theory and an atomic Bomb. Wells's novel [The Shape of] Things To Come, turned into a 1936 film, [Things to Come], accurately predicted aerial bombardment and an imminent devastating world war.

In 1939 Szilard drafted the letter Albert Einstein sent to President Roosevelt warning America that Germany was stockpiling uranium. The Manhattan Project was born.

Szilard and several British scientists worked on it with the US military's massive financial backing. Britons and Americans worked alongside each other in "silos" – each team unaware of how their work fitted together. They ended up moving on from the original enriched uranium "gun" method, which had been conceived in Britain, to create a plutonium implosion weapon instead.

Szilard campaigned for a demonstration bomb test in front of the Japanese ambassador to give them a chance to surrender. He was horrified that it was instead dropped on a city.

In 1945 Churchill was beaten in the general election and in another shock, the US government passed the 1946 McMahon Act, shutting Britain out of access to the atomic technology it had helped create. William Penney, one of the returning Los Alamos physicists, led the team charged by Prime Minister Clement Atlee with somehow putting together their individual pieces of the puzzle to create a British bomb on a fraction of the American budget.

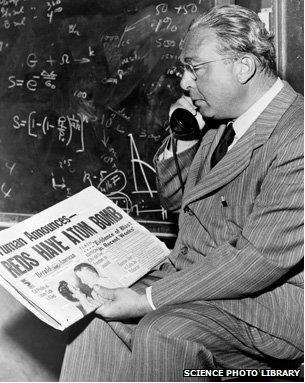

Leo Szilard

"It was a huge intellectual feat," Andrew Nahum observes. "Essentially they reworked the calculations that they'd been doing in Los Alamos. They had the services of Klaus Fuchs, who [later] turned out to be an atom spy passing information to the Soviet Union, but he also had a phenomenal memory."

Another British physicist, Patrick Blackett, who discussed the Bomb after the war with a German scientist in captivity, observed that there were no real secrets. According to Nahum he said: "It's a bit like making an omelette. Not everyone can make a good one."

When Churchill was re-elected in 1951 he "found an almost complete weapon ready to test and was puzzled and fascinated by how Attlee had buried the costs in the budget", says Nahum. "He was very conflicted about whether to go ahead with the test and wrote about whether we should have 'the art and not the article'. Meaning should it be enough to have the capability... [rather] than to have a dangerous weapon in the armoury."

Churchill was convinced to go ahead with the test, but the much more powerful hydrogen bomb developed three years later worried him greatly.

HG Wells died in 1946. He had been working on a film sequel to The Shape of Things To Come that was to include his concerns about the now-realised atomic bomb he'd first imagined. But it was never made.

Towards the end of his life, says Nahum, Wells's friendship with Churchill "cooled a little".

"Wells considered Churchill as an enlightened but tarnished member of the ruling classes." And Churchill had little time for Wells's increasingly fanciful socialist utopian ideas.

Wells believed technocrats and scientists would ultimately run a peaceful new world order like in The Shape of Things To Come, even if global war destroyed the world as we knew it first. Churchill, a former soldier, believed in the lessons of history and saw diplomacy as the only way to keep mankind from self-destruction in the atomic age.

Wells's scientist acquaintance Leo Szilard stayed in America and campaigned for civilian control of atomic energy, equally pessimistic about Wells's idea of a bold new scientist-led world order. If anything Szilard was tormented by the power he had helped unleash. In 1950, he predicted a cobalt bomb that would destroy all life on the planet.

In Britain, the legacy of the Bomb was a remarkable period of elite scientific innovation as the many scientists who had worked on weaponry or radar returned to their civilian labs. They gave us the first commercial jet airliner, the Comet, near-supersonic aircraft and rockets, highly engineered computers, and the Jodrell Bank giant moveable radio telescope.

The latter had nearly ended the career of its champion, physicist Bernard Lovell, with its huge costs, until the 1957 launch of Sputnik, when it emerged that Jodrell Bank had the only device in the West that could track it.

Nahum says Lovell reflected that "during the war the question was never what will something cost. The question was only can you do it and how soon can we have it? And that was the spirit he took into his peacetime science."

Austerity and the tiny size of the British [economy], compared with America, were to scupper those dreams. But though the Bomb created a new terror, for a few years at least, Britain saw a vision of a benign atomic future, too and believed it could be the shape of things to come.