Verses and Imitations

William Wardlaw Waddell was clearly a man of tremendous erudition and linguistic accomplishment (Greek, Latin, Scots, French and Italian all feature herein), and I've wondered who his target audience might have been. Almost all the items appear in two languages, printed in parallel, and would, I suppose, provide excellent practice for students of both classical and modern languages.

And as he was an Inspector of Schools by profession, and often called upon as guest of honour at school prize-giving occasions, I think he had probably intended to present copies of Verses and Imitations to the pupils who were showing particular promise in these directions. Lucky them!

But in the Introduction he intimates that he was by then (1890) retired, or on the verge of retirement, possibly for reasons of ill-health, though he survived for another 13 years. We Waddells attract bodily ills as the sparks fly upwards, and are indefatigable valetudinarians, though the dwaibly Findlays run us close.

It's actually quite difficult to scan on a flat-bed scanner, and, for the time being, only the first few images are displayed below.

This is indeed the archetypical "Slim Volume", measuring only 7⅛" x 4½", and a mere ½" thick, and containing just 103 pages (ie 52 sheets of rag paper, rather bohemianly rough-cut).

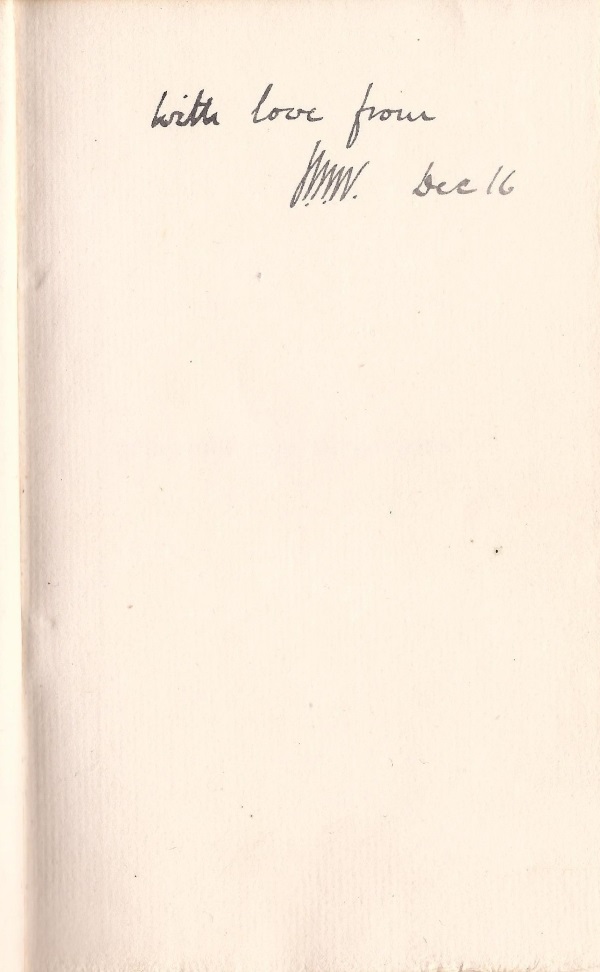

It's interesting to speculate who the object of WWW's affectionate inscription might have been, and I think it was probably his nephew Peter Hately Waddell minimus, born 15 Dec 1881, who was probably already showing signs of being another outstanding classicist.

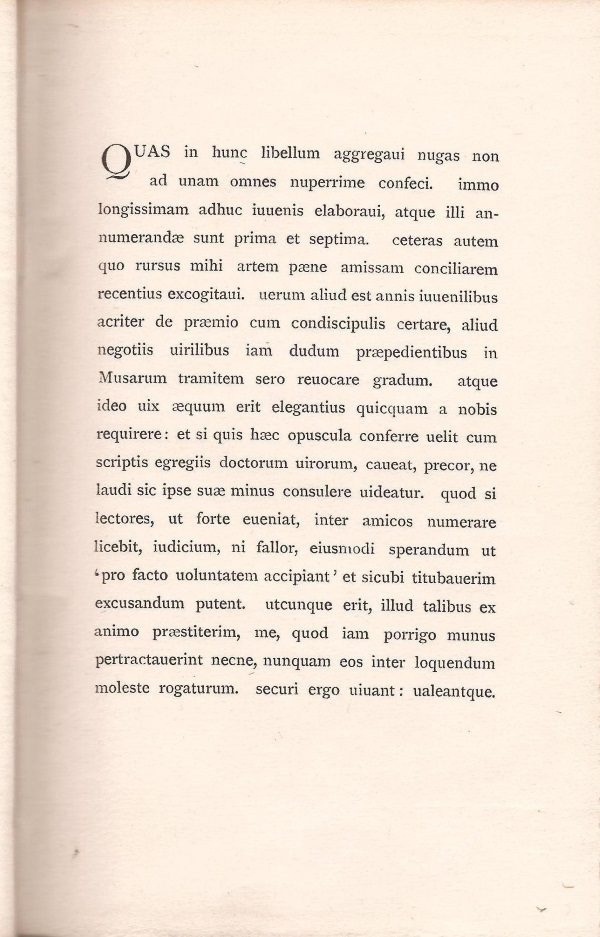

See below for transcription and translation

This may be more helpfully rendered into separate sentences, with the first letter of each being capitalised.

Quas in hunc libellum aggregavi nugas non ad unam omnes nuperrime confeci.

Immo longissimam adhuc juvenis elaboravi, atque illi annumerandae sunt prima et septima.

Ceteras autem quo rursus mihi artem paene amissam conciliarem recentius excogitavi.

Verum aliud est annis juvenilibus acriter de praemio cum condiscipulis certare, aliud negotiis virilibus iam dudum praepedientibus in Musarum tramitem seron revocare gradum.

Atque ideo vix aequum erit elegantius quicquam a nobis requirere: et si quis haec opuscula conferre velit cum scriptis egregiis doctorum virorum, caveat, precor, ne laudi sic ipse suae minus consulere videatur.

Quod si lectores, ut forte eveniat, inter amicos numerare licebit, judicium, ni fallor, eiusmodi sperandum ut 'pro facto voluntatem accipiant' et sicubi titubaverim excusandum putent.

Utcunque erit, illud talibus ex animo praestiterim, me, quod iam porrigo munus pertractaverint necne, nunquam eos inter loquendum moleste rogaturum.

Securi ergo vivant: valeantque

Transcription

Note also that I've instinctively transcribed many of WWW's u's into v's, though I'd be hard-pressed to explain why, though in part it's because classical Latin (as I studied fitfully at school in the 1950's) used only 22 letters – omitting the modern j, u, w and y. Furthermore, we were taught to pronounce v's as w's!

In my father's inattentive days at school in the 1920's, many of today's i's were rendered as j's, and v's were pronounced as v's, dammit.

However, as once remarked (probably by Saki), nineteenth century German scholars improved the classical languages, their spelling, and their pronunciation to an extent unrecognisable to the people who originally spoke them. English scholars apparently lagged behind their German counterparts, and WWW's usage (as a Scot) appears to be somewhere in between.

Ironically of course, the German tribes had firmly resisted all Roman attempts to conquer and civilise them. And anyway, the ordinary people of Rome apparently spoke demotic, a variant of Greek, and the official language was reserved for oratory, literature, legal scrolls and public inscriptions in stone.

The trifles that I have gathered into this pamphlet have not all been brought together into one place until very recently.

Indeed, I worked on the longest of them while still a youth, and to it should be added the first and the seventh.

The rest, however, I have devised more recently, in order to reacquire for myself an art that I had almost lost.

To be sure, it is one thing to contend keenly in one's youth with fellow-pupils for a prize, but it is another, after long being shackled by men's affairs, to retrace one's steps late in life along the path of the Muses.

For that reason it would scarcely be justified for anyone to demand anything more elegant from us, and if anyone wishes to compare these little works with the distinguished writings of learned men, I beg him to take care to safeguard his own reputation.

But if I may perhaps be allowed to number my readers among my friends, the judgment I would hope for (if I may) is that they 'take the will for the deed' and consider excusing any point at which I may have faltered.

Come what may, I shall take one thing to heart in this regard – I shall never trouble them in conversation by enquiring whether or not they have studied this work that I am now offering.

And thus they may live free from care, and may they fare well.

www.kerrywood.co.uk traduxit

Translation