The Highland Clearances

Like a good many other people, in all probability, I find the modern usage of the word "cleansing" deeply distasteful, and in fact quite disgusting, when applied to the forcible relocation or murder of large numbers of people whom the "cleansers" regard as being of the wrong race or religion, or being simply inconvenient in some way or another.

If nothing else, it's a debasement of a perfectly good word, with healthy and hygienic connotations, which are being subtly extended to insinuate that the people concerned are in some respect dirty, infectious or noisome.

There are those such as the prominent Times journalist who regularly argues, like Humpty Dumpty, that anybody is allowed to assign any meaning they like to a word, and if they do so in sufficient numbers, any particular distortion must eventually be regarded as correct: Vox populi, vox linguae.

George Orwell would have a field day with such arguments. As he forcefully pointed out, the deliberate misuse of language in politics is invariably a factor in creeping totalitarianism, because it dulls and confuses the mind. And it is equally dangerous in sloppy, materialistic democracies, because it muddles social values and moral convictions, so that ultimately a sort of Second Law of Thermolinguistics prevails, in which anything is as good as anything else.

What on earth has this linguistic bee in my bonnet got to do with the Highland Clearances, which began in the late 18th century and persisted well into the 19th? The Highlanders were desperately poor, spoke Gaelic rather than English, were often Catholic or Episcopalian rather than Presbyterian, and occupied grazing land that if aggregated together could be used much more profitably with much larger flocks of sheep, by their feudal landowner.

Of course, the landowner didn't put it to them so bluntly. He (or she) said, via his factors, that the villagers would be far better off if they moved down to the coast and took up, er, fishing as a livelihood. Indeed, they could emigrate to America ... He may even have used financial inducements.

But the Highlanders didn't want to move. They were fiercely attached to their traditional way of life, and the rugged grandeur of their mountainous scenery. They probably asked themselves the Gaelic equivalent of "Cui bono?" and decided that the answer wasn't them.

So they resisted stubbornly, and they were set upon, chivvied and frequently murdered. Their villages were set aflame. They were being "ethnically cleansed" in today's anodyne euphemism. And a good many Scots still feel bitterly, and justifiably, aggrieved about it – indeed the SNP (Scottish National Party) has pledged to break up many of the large estates in Scotland and return them to popular use.

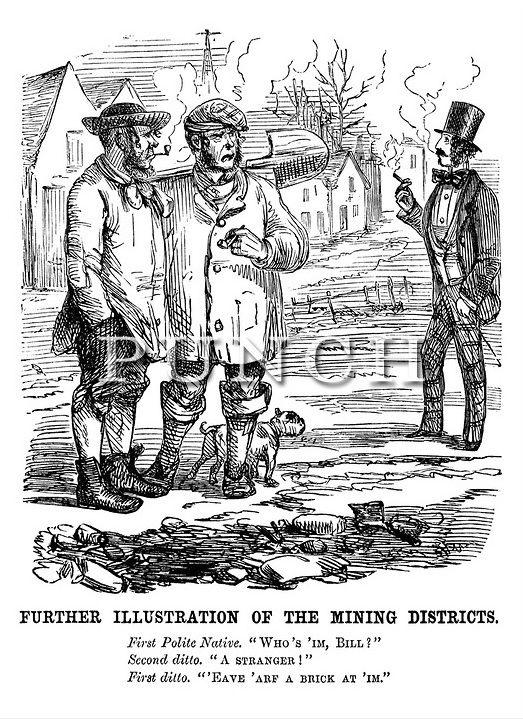

Similar things had been going on in England and Ireland for a long time. In fact of course, "ethnic cleansing" has been going on for thousands of years in societies around the world. Antipathy, or even outright hostility, to those who are somehow different to ourselves seems to be an ineradicable human instinct – as witness the famous Punch cartoon, in which two locals regard a well-dressed individual who appears to be from elsewhere ...

There are innumerable accounts on the internet1, 2, 3, etc and in print §, etc of the Highland Clearances and the particularly notorious part played by Lord and Lady Stafford (as the 1st Duke and Duchess of Sutherland were then called). One in particular ¶ has caught my attention, in a book written nominally for children, but which (like all the best books for children) can be read with equal pleasure or profit by adults.

It's a remarkable polemic, without fear or favour and marvellously illustrated – pretty scabrous about the English, of course, and sometimes about the Scots themselves too. As far as I'm aware, the Highland Clearances were actioned with equal glee by landowners of either descent, English or Scottish. But there was no doubt about the Duke of Sutherland – the Leverson-Gowers were English, as Terry Deary points out, but his factor Patrick Sellar was Scottish (and was the grandfather of W C Sellar, co-author of the impenetrably English humorous classic 1066 and All That, which has to be accounted to his credit side).

That George Granville Leveson-Gower and his wife are so deeply detested by the Scots to this very day gives some idea of the odium in which they were held just under a century ago when the Prince of Wales was debarred from marrying their great grand-daughter Rosemary, in part because of her connection with them.

§ An Illustrated History of Scotland; Elisabeth Fraser, publ Jarrold Publishing, 1997; pp 108-121

¶ Bloody Scotland (a Horrible Histories Special); Terry Deary, publ Scholastic Children's Books, 1998; pp 143-149

One of the more inexplicable aspects of the Eastern European vampire tradition is that the bat-winged blood-sucker has to be invited in before he's able to cross your threshold. You'd think that the potential victim wouldn't fall for that, but she generally did – otherwise there'd be no tradition of course.

What am I getting at, you may well sigh?

My point is that the accursed Normans conquered England, land of the intensely egalitarian Anglo-Saxons, by subterfuge and force, and then proceeded to harry and ravage all pockets of resistance into submission. But to initiate the subjugation of Scotland and Ireland they had to be invited in (Wales was slightly different, though equally sneaky).

They were invited into Scotland by King David I, and into Ireland by King Dermot of Leinster, and the reverberations of those two awful miscalculations echo to this day. The IRA's stirring traditions sing that "The Saxon comes with his long-range guns ...", but for Saxon that should read Norman.

The Celtic tradition was even more egalitarian than the Anglo-Saxon one, but we each got stuffed in due course by the Normans (who of course were also busy carving out an empire in the Mediterranean and Levantine regions).

The Anglo-Saxons were governed by an elected King and his jarls (or Earls, easy-going individuals who mostly preferred feasting and drinking to bossing the peasantry around). The Highland Scots were governed by a very remote King and their more immediate clan chiefs to whom their real allegiance lay. The imposition of the rigid Norman feudal system would cause centuries of strife, unresolved to this day.