Narratives, both published and personal

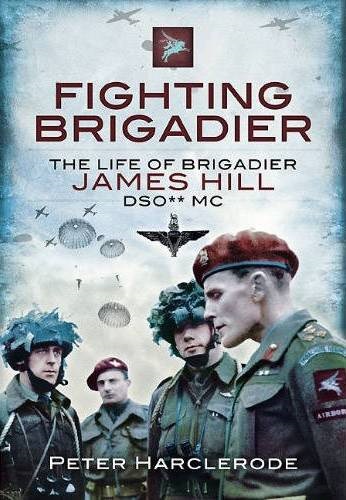

Brigadier James Hill is recognised in Airborne circles as a founding father of The Parachute Regiment, yet his story has not been told until now. Commissioned in 1931 into the Royal Fusiliers, he had to leave the Army five years later because he married under-age. Recalled in 1939, he won his MC with the British Expeditionary Force in France.

An early Airborne Forces volunteer, he joined 1st Parachute Battalion as second - in - command in May 1942. In October by now in command, he took the battalion to North Africa where he earned his first DSO. Badly wounded, he was evacuated back to Britain where he assumed command of the newly formed 9th Parachute Battalion in early 1943. Promoted to brigadier, he formed 3rd Parachute Brigade, which he commanded throughout the Normandy campaign. Wounded twice, he earned a bar to his DSO.

Hill and his brigade returned with 6th Airborne Division to England in September 1944 before fighting in the winter Battle of the Bulge. In March 1945, 3rd Parachute Brigade played a key role in the Rhine Crossing, and the advance to the Baltic in a race against time to block the Russian advance on Denmark. For these and other outstanding achievements Hill received a second bar to his DSO, the US Silver Star and King Haakon VIII of Norway's Liberty Cross.

Post-war, James Hill was a greatly respected figure in The Parachute Regiment, instrumental in forming The Parachute Regimental Association and serving on the Regimental Council for 30 years. In 1974 he was appointed Chairman of the Airborne Assault Normandy Trust, later becoming President and Vice-Patron.

James Hill died in 2006 aged 95. His life-size bronze statue stands prominently at Pegasus Bridge; a fitting memorial, as is this overdue biography, to the Fighting Brigadier.

Brigadier 'Speedy' Hill

18 Mar 2006

Brigadier "Speedy" Hill, who died on Thursday aged 95, won an MC and three DSOs as a commander of airborne forces during the Second World War.

In 1942 Hill took command of the 1st Battalion, Parachute Regiment, which was dropped at Souk El Arba, deep behind enemy lines in Tunisia. His orders were to secure the plain so that it could be used as a landing strip and then to take Beja, the road and rail centre 40 miles to the north east, in order to persuade the French garrison to fight on the Allied side.

To impress the French commander with the size of his unit, Hill marched the battalion through the town twice, first wearing helmets and then changing to berets. The Germans, hearing reports that a considerable British force had occupied Beja, responded by bombing the town.

On learning that a mixed force of Germans and Italians, equipped with a few tanks, was located at a feature called Gue, Hill put in a night attack. But a grenade in a sapper's sandbag exploded, setting off others, and there were heavy casualties when the element of surprise was lost.

Two companies carried out an immediate assault while Hill, with a small group, approached three light tanks. He put the barrel of his revolver through the observation port of the first tank and fired a single round. The Italian crew surrendered at once. He banged his thumbstick on the turret of the second tank, with the same result.

But when he used the method on the third tank, the German crew emerged, firing their weapons and throwing grenades. They were dealt with in short order, though Hill took three bullets in the chest. He was rushed to Beja, where Captain Robb of the 16th Parachute Field Ambulance operated on him and saved his life.

The citation for Hill's first DSO paid tribute to the brilliant handling of his force and his complete disregard of personal danger. The French recognised his gallantry with the award of the Légion d'Honneur.

Stanley James Ledger Hill, the son of Major-General Walter Hill, was born at Bath on March 14 1911. Young James went to Marlborough, where he was head of the OTC, and then won the Sword of Honour and became captain of athletics at Sandhurst.

Nicknamed "Speedy" because of the long strides he took as a tall man, he was commissioned into the Royal Fusiliers, with whom he served with the 2nd Battalion, and ran the regimental athletic and boxing teams.

In 1936 he left the Army to get married, and for the next three years worked in the family ferry company. On the outbreak of war Hill rejoined his regiment, and left for France in command of 2RF's advance party. He led a platoon on the Maginot Line for two months before being posted to AHQ as a staff captain.

In May 1940, Hill was a member of Field Marshal Viscount Gort's command post, playing a leading part in the civilian evacuation of Brussels and La Panne beach during the final phase of the withdrawal. He returned to Dover in the last destroyer to leave Dunkirk, and was awarded an MC.

Following promotion to major and a posting to Northern Ireland as DAAG, Hill was dispatched to Dublin to plan the evacuation of British nationals in the event of enemy landings. He booked into the Gresham Hotel, where several Germans were staying at the time.

Hill was one of the first to join the Parachute Regiment and after being wounded in Tunisia in 1942, he was evacuated to England. Although forbidden to take exercise in hospital, he used to climb out of his window at night to stroll around the gardens. Seven weeks later, he declared himself fit and, in December, he converted the 10th Battalion, Essex Regiment, to the 9th Parachute Battalion.

In April the following year, Hill took command of 3rd Parachute Brigade, consisting of the 8th and 9th Parachute Battalions and the 1st Canadian Parachute Battalion, which he commanded on D-Day as part of the 6th Airborne Division.

Given the task of destroying the battery at Merville and blowing bridges over the River Dives to prevent the enemy bringing in reinforcements from the east, he completed the briefing of his officers with the warning: "Gentlemen, in spite of your excellent training and orders, do not be daunted if chaos reigns. It undoubtedly will."

Things began to go wrong straight away. Many of the beacons for marking the dropping zones were lost, and several of the aircraft were hit or experienced technical problems. Hill landed in the River Dives near Cabourg, some three miles from the dropping zone, and it took him several hours to reach dry land.

The terrain was criss-crossed with deep irrigation ditches in which some of his men, weighed down by equipment, drowned.

Since he did not trust radio, he kept in touch by driving around on a motorcycle, periodically being found directing traffic at crossroads by his advancing men. Near Sallenelles, Hill and a group of men of the 9th Parachute Battalion were accidentally bombed by Allied aircraft; 17 men were killed.

Hill was injured but, after giving morphia to the wounded, he reported to his divisional commander, who confirmed that the battery at Merville had been captured after a ferocious fight, and that Hill's brigade had achieved all its objectives.

Hill underwent surgery that afternoon, but refused to be evacuated and set up his headquarters at La Mesnil. Under his leadership, three weak parachute battalions held the key strategic ridge from Chateau St Côme to the outskirts of Troarn against repeated attacks from the German 346th Division.

On June 10 the 5th Battalion, Black Watch, was put under Hill's command. Two days later, when the 9th Parachute Battalion called for urgent reinforcements, Hill led a company of Canadian parachutists in a daring counter-attack.

The 12th Parachute Battalion, took Bréville, the pivotal position from which 346th Division launched their attacks on the ridge, albeit at great cost. Hill said afterwards that the enemy had sustained considerable losses of men and equipment and a great defensive victory had been won. He was awarded a Bar to his DSO.

The 3rd Parachute Brigade returned to England in September but three months later it was back on the front line, covering the crossings of the River Meuse. In the difficult conditions of the Ardennes and in organising offensive patrolling across the River Maas, Hill's enthusiasm was a constant inspiration to his men.

In March 1945 Hill commanded the brigade in Operation Varsity, the battle of the Rhine Crossing, before pushing on to Wismar on the Baltic, arriving on May 2, hours before the Russians.

He was wounded in action three times. He was awarded a second Bar to his DSO, and the American Silver Star. Hill was appointed military governor of Copenhagen in May and was awarded the King Haakon VII Liberty Cross for his services. He commanded and demobilised the 1st Parachute Brigade before retiring from the Army in July in the rank of brigadier.

He was closely involved in the formation of the Parachute Regiment Association and, in 1947, he raised and commanded the 4th Parachute Brigade (TA).

The next year, Hill joined the board of Associated Coal & Wharf Companies and was president of the Powell Duffryn Group of companies in Canada from 1952 to 1958. He was managing director and chairman of Cory Brothers from 1958 to 1970.

In 1961, Hill became a director of Powell Duffryn and was vice-chairman of the company from 1970 to 1976. Among a number of other directorships, he was a director of Lloyds Bank from 1972 to 1979.

He was for many years a trustee of the Airborne Forces Security Fund and a member of the regimental council of the Parachute Regiment. In June 2004, he attended the 60th Anniversary of the Normandy landings.

A life-size bronze statue of him with his thumbstick, sited at Le Mesnil crossroads, the central point of the 3rd Parachute Brigade's defensive position on D-Day, was unveiled by the Prince of Wales, Colonel-in-Chief of the Parachute Regiment.

James Hill married first, in 1937, Denys Gunter-Jones, with whom he had a daughter and, in 1986, Joan Haywood. At Chichester in his final years he enjoyed pursuing his lifelong hobby of birdwatching.

This is James Hill's account of his D-Day experiences:

I was born in 1911 and went to Sandhurst in 1929. After a spell as an army officer I went into the family business, but I was called up for duty when war broke out in 1939.

In the run-up to D-Day I was commanding the 3rd Parachute Brigade in the 6th Airborne Division. The brigade had been formed in the beginning of 1943 with the sole purpose of taking part in the Normandy landings. The brigade was made up of three county battalions. These battalions were invited to join the parachute brigade, and being good chaps they volunteered to a man.

These chaps were the salt of the earth, prepared to give their lives without arguing the toss. They hadn't joined the army to parachute, but we said, 'Please parachute,' and they said, 'We'll try.'

Training for D-Day

During the physical training we focused on four objectives: speed, control, simplicity and fire effect.

As parachutists we didn't carry much equipment, and we had to make use of this advantage to achieve great speed. If you could give orders twice as fast as anyone else you could gain ten minutes on the enemy.

Coupled with speed was control - it was no good having expensive paratroops if they weren't under control. Simplicity was vital - the simpler things were, the fewer mistakes were made. Fire effect was essential because we didn't carry much ammunition, so every shot had to count.

In order to achieve these four objectives we had to become amazingly fit. The initial training was extremely hard, and many of the volunteers left - they simply couldn't stand the pace of the training.

We knew we would have to fight at night so we spent a great deal of time doing night-time training. For one week every month my brigade used to operate at night, sleeping during the daytime. Of course that was marvellous for all the chaps, but the poor brigade commander still had to spend the day doing administrative work!

I was always keen for my brigade headquarters to do just as well as the chaps of the battalions, so on one occasion I took them for a two-hour march carrying 60 pounds of equipment. This of course included the clerks and the telephone operators! As we were staggering into the town of Bulford I was cheering them on, as you do, so that they would get to the end within the two hours.

On the following Monday I received a notice saying that a deputation from the local Women's Institute wanted to see the brigade commander. They had come to complain about the way I had shouted at the chaps to finish - they thought it had been cruel and brutal. That rather amused me!

It's a dog's life

From January 1943 until D-Day in June 1944, we had to keep the chaps interested and on top form. One of the things I introduced in order to do that was parachuting dogs. A team of paratroops were trained in handling Alsatian messenger dogs. The dogs were given bicycle parachutes, as they were roughly the same weight as bicycles. The first time we took one of the dogs up he didn't want to jump, so we shoved him out. It turns out he enjoyed himself so much that the next time he couldn't wait to go! The dogs were trained to be messengers, but they were really just a sideshow to keep the men amused.

Carrots for night vision

At that time there were two fighter pilots who became known for being highly successful at shooting the enemy down at night - Cat's Eyes Cunningham and a chap called White Boycott, who had been at school with me. Rumour was that they were so good at night fighting because they ate a lot of carrots, and so we also ate carrots until we were quite sick of the things.

I was lucky enough to have lunch with Cat's Eyes Cunningham recently, just before he died, and he told me that their success had nothing to do with eating carrots. The carrot story was just a ruse to prevent the enemy from finding out that they were equipped with the very latest form of radar.

Getting the men to church

I wanted all of my brigade to go to church at least once a month, but some of the chaps didn't like this very much. So to motivate them I would make them carry 60 pounds of equipment to church, which they stacked up outside under guard before going inside. After the service I would take them for a 20-mile march. I thought that might motivate them to enjoy their time at church a bit more!

The interesting thing is that, after D-Day, a number of people told me what a difference those church visits had made. When we were crossing the North Sea on D-Day it was a pretty rough night, and sitting in those planes were men of 22 who had never seen a shot fired in anger and were now flying into enemy territory. Up against something like that, even an atheist wants to pray.

Boosting morale

Napoleon said that 'the moral is to the physical as two is to one'. I found that if you are very fit, your morale is automatically good, and I put an awful lot of effort into getting the chaps extremely fit. It's amazing what a fit young body can take in the way of wounds and survive.

The other thing that is important for morale is to be fighting a noble cause. I could not have fought for six years if I hadn't believed our cause to be completely right. I was asking those chaps to possibly die for the cause, I had to believe the cause to be true.

I loved the men of my brigade, and if you love people they'll love you too, they'll follow you, and they'll have respect for you.

Landing in France

On the night of D-Day we landed in four and a half feet of water in a flooded valley. It was an inaccurate landing, but it could have been worse, as the valley is criss-crossed by irrigation ditches, some of them 14 feet deep. With 60 pounds of equipment, falling into a ditch like that would have meant going down.

The landing was inaccurate because the pilots who flew us over to Normandy had been bomber pilots until about six weeks before D-Day. They had been used to bombing cities from 10,000 feet, now they had to drop paratroops from 700 feet onto a drop zone about 1,000 metres square. I had suspected that the drops might be inaccurate, and had said to my men some weeks before, 'Gentlemen, in spite of your excellent training and very clear orders, don't be daunted if chaos reigns - because it certainly will.'

After the landing we gathered about 42 chaps, and tied ourselves together with our toggle ropes. It meant we were all in control, and if we came across wire under water, we were all there to deal with it.

Attacked from the air

After about 45 minutes marching along a narrow path with bog on both sides, I suddenly heard a horrid noise. I had seen a lot of fighting and knew it was an attack by low-flying aircraft dropping anti-personnel bombs, so I shouted to the chaps to get down. I threw myself down on top of a chap called Lieutenant Peters.

The aircraft passed over and there was the horrible smell of cordite and death hanging in the air. I knew I'd been hit. I saw a leg lying in the middle of the path and I thought, by God that's mine. Then I noticed it had a brown boot on. I didn't allow brown boots in my brigade, and the only person who broke that rule was my friend Lieutenant Peters. I was lying on top of him. He was dead, I wasn't - but I'd been hit and a large chunk of my left backside was gone.

Only two of us were able to get up. The dead and injured were all around us. I was faced with the choice: do I stay and look after the injured, or do I press on? As brigade commander I had a great responsibility, so I had to press on. Before leaving we took the morphine from the dead, and gave it to the living. We set off and the injured chaps gave us a cheer. That memory is as vivid today as it ever was. It was a ghastly sight.

My mother was a soldier's wife, and at the outbreak of war she said to me, 'Darling, if you're going to survive this war, you've got to learn to harden your heart.' That was good advice. You could have a hard heart and still have compassion, and I was full of compassion for the people I left there. But as commander, I had to go where my most important task lay.

The Germans threw the bodies of those chaps into a big shell hole, but a few days later we captured the area and unearthed them, and gave them each a proper burial.

Finding the 9th Battalion

It took us four and a half hours to get to the drop zone where we were meant to have landed in the first place. There I found out my Canadian battalion had achieved their objective to destroy or capture a nearby enemy headquarters.

From there we set off to the battery which Terence Ottway and the men of the 9th Battalion were meant to be capturing before 5.30pm. As we were walking along, dawn was breaking and we saw the most amazing display of fireworks, and heard the thunderous noise of guns as the troops and ships started attacking the shoreline. It was a remarkable sight to see from behind the front line, and it was very encouraging because we knew then that we weren't alone.

As I was approaching the ridge where the 9th Battalion was fighting I passed the field dressing station. The doctor there took one look at me and said, 'James, you look bad for morale.'

I said, 'If you had been in four and a half feet of cold water for hours and then had your left backside shot off, you wouldn't feel good for morale either.'

The doctor told me that Colonel Ottway had taken the battery with just 70 men. Their average age was 22, they'd never seen a shot fired before and all their plans had gone awry - but they achieved their objective.

The doctor said he would give me an injection that would help me, but in fact it knocked me out for about two hours. In this time he patched up my behind. When I came to again they had a ladies' bicycle for me, and a chap who could push it. I very gingerly sat on the back of this bicycle and was pushed down the road to the divisional headquarters. Sometimes we saw Germans running across the road, sometimes Brits, but they were all too busy to worry about a shabby-looking brigade commander on a ladies' bicycle.

At the divisional headquarters at Ranville I met our divisional commander, and the first thing he said to me was, 'James, you'll be delighted to know that your brigade has taken all its objectives.'

A field operation

Just then the ADMS, who is the head doctor in the division, turned up and seized me by the collar, saying, 'I'm taking you off to the main dressing station to have an operation.' I was very unwilling to go, but he promised that he would personally take me back to the brigade headquarters.

As I lay there waiting for my operation at about 1pm, I heard a dense shelling, and thought to myself, 'I hope that the Brits will still be here when I come to, and not a lot of Germans.'

When I came to at about 3pm I was told that I was the first person to be given penicillin, which had just been invented. I had a bottle strapped to my side, and attached to it were tubes that carried penicillin dripping into my wounds. It was rather undignified - half my backside and my trousers shot away, and as brigade commander I usually liked to keep up a bit of style.

We got into a jeep to drive to brigade headquarters, with me balancing myself on my right side. We got there at about 4pm. Alistair Pearson, one of the greatest fighting battalion commanders of the war, had taken command of the brigade in my absence. He was OK apart from having been shot through the hand.

Go, guts and gumption

Communication was obviously difficult on the day. My signaller had been dropped away from me, so until I got to brigade headquarters, my only means of communication was verbal. From headquarters I could keep an eye on the Canadians, and Terrence Ottway was just half a mile away. It was more difficult to communicate with Alistair Pearson of the 8th Battalion, who was about two miles down the road.

But that was the parachuting game - it was part of our training to expect the unexpected. You knew exactly where you had to be and what you had to do, and if things went wrong you had to put them right personally. Our chaps showed great individuality and got themselves out of the most surprising predicaments, like being dropped behind enemy lines.

On the ridge we were fighting a top-ranking German division, 346 Panzer Grenadier Division. They had their own tanks, their own ak-ak guns - everything. But our chaps were tough. We started off with 2,200 men and ended up with about 700 at the most. We were able to see off a fresh infantry division with limited equipment, and the only reason we could do that was through sheer guts.

As a brigade commander going into battle, you have a beautiful map case and sharp pencils, but there I was, minus half my backside, minus a pair of trousers, and all our chaps were in exactly the same boat. It was go, guts and gumption.

The end of the beginning

At the end of D-Day I was sitting at what I called my command post, on the steps leading up to a barn where I had my sleeping bag. Then, away to the south west, I suddenly saw hundreds of gliders coming in. It was the second wave of the 6th Airborne Division, gliding into battle.

It was a wonderful sight. I knew they were carrying supplies, and the sight of them coming in to land made me feel less lonely, just as the sounds of the dawn battle had that morning. I said to myself, 'Remember all these things, because you're never going to see a sight like this again.'

It was a great relief to know that we'd got to France, we had captured our objectives, and we were exactly where we were supposed to be. We knew we still had a fight on our hands, but we had landed. We had a little bit of France and those gliders coming in to land were following us. The battle started from there. Not with beautiful clean clothes and a nice map case, but worn out, wet, dirty and smelly.

Brigadier Stanley James Ledger Hill DSO, MC

Unit: Brigade HQ, 3rd Parachute Brigade

Service No.: 52648

Awards: 2nd Bar to the Distinguished Service Order, Military Cross, Legion d'Honneur, Silver Star, King Haakon VII Liberty Cross.

James Hill was born in 1911. He attended Sandhurst in 1929 and thereafter served as an officer in the Royal Fusiliers before returning to civilian life and a family business. He was recalled to the Army at the outbreak of War, and in 1940, during the Battle of France, he served as a Captain on Lord Gort's staff at the Headquarters of the British Expeditionary Force. For his conduct during the campaign he was awarded the Military Medal. His citation reads:

This officer was detailed to undertake duties in the forward areas in connection with traffic control and the evacuation of refugees. These duties he carried out with enthusiasm and skill, and was often placed in positions of great personal danger. During the final embarkation he was employed at Dunkirk.

He performed valuable work throughout, and I recommend him for the award of the Military Cross.

Following the withdrawal from Dunkirk he joined the Parachute Regiment as one of its earliest members and, after a period as their Second-in-Command, he was promoted to Lieutenant-Colonel in 1942 and given command of the 1st Parachute Battalion. Towards the end of that year, the Battalion, together with the 1st Parachute Brigade, of which it was a part, was transferred to North Africa. In November 1942, each of the three battalions of the Brigade were called upon to undertake one action or another in Tunisia, with varying degrees of success. On the 16th November, the 1st Battalion were dropped deep behind the enemy lines. Their initial task was to secure the Souk el Khemis-Souk el Arba plain so that the RAF could use it as a landing strip, but their chief purpose was to enter the town of Beja and persuade the three-thousand-strong neutral French garrison to fight on the side of the Allies. With this achieved, the 1st Battalion, with the assistance of the French, were to use the town as a firm base from which to harrass the Germans and Italians in their area. The drop went very well and the Battalion received an enthusiastic welcome from the French soldiers in the town. Lieutenant-Colonel Hill felt that the locals might be more encouraged to join the Allied cause if they were made to believe that his force was stronger than it was, and to achieve this he marched the Battalion through the town twice, altering their appearance the second time around by removing their red berets. With the French firmly on his side, Hill decided to cement the relationship by sending his men straight into action. He had been informed that the Germans carried out a routine and regular patrol of a nearby road and so he sent a force to ambush it, which was achieved most effectively.

On the 22nd November, Lieutenant-Colonel Hill discovered that there was a force of some three-hundred Italian soldiers in the vicinity and he made plans to attack them during the night. Attached to the Battalion was a company of French Senegalese soldiers and a group of Royal Engineers, who were to mine the road to the rear of the enemy position to thwart their escape or reinforcement. Unfortunately as the Engineers were moving forward, a faulty grenade amongst their stores exploded and in so doing set off other grenades, a tragedy which killed twenty-five of the twenty-seven sappers. With the enemy alerted and opening fire in response, the 1st Battalion's "R" and "S" Companies immediately attacked what proved to be a mixed force of German and Italian soldiers. The enemy was accompanied by three Italian light tanks, and James Hill took it upon himself to personally force the surrender of their crews. Taking advantage of the general unwillingness of the Italian to fight, he decided not to be too harsh with them. When he approached the first tank he inserted his revolver through an observation port and fired a single shot, which prompted the crew to come out. The second vehicle was similarly disarmed, but with this one he only felt the need to bang on the side of the tank's turret with his walking stick. The third tank, however, contained German soldiers and they came out fighting. They were all killed by members of Hill's party within moments but, caught unawares, Hill himself was hit by three bullets, one went through his chest, another hit his shoulder and the other struck his neck. Hill's wounds were very serious and so he was placed in the sidecar of an Italian motorcycle, together with another badly wounded officer, and driven back to Beja where his life was saved on the operating table. Hill was evacuated to a hospital in Algiers whilst command of the Battalion passed to his deputy, Lieutenant-Colonel Alastair Pearson. The 1st Battalion withdrew to Algiers ten days later.

For his actions behind the lines with the 1st Battalion, Hill was awarded the Distinguished Service Order. His citation reads:

For inspiring leadership and undaunted courage. This officer who led his Battalion after a flight of some 400 miles, and a parachute drop, displayed on every occasion conspicuous gallantry under heavy enemy fire. Leading his Battalion in raids against enemy A.F.V's he personally destroyed at least two and was mainly responsible for the successful results achieved. In a raid on an enemy post he led his Battalion forward under heavy machine gun fire and by his utter disregard of personal danger, and by his brilliant handling, was successful in entirely destroying the post and capturing a number of prisoners. This leadership and courage was an inspiration not only to his own troops but also to the French who recognised his gallantry by the award of the Legion d'honneur. On one occasion although severely wounded he continued to command his battalion until the successful completion of the operation.

Hill was impatient to resume command of his Battalion and so set about getting himself fit as soon as he felt able. He was forbidden to take exercise, but he chose to ignore this advice by climbing out of his window at night to stroll through the hospital gardens. Seven weeks later he declared himself fit and simply strolled out of the hospital and reported to his commander, Brigadier Flavell. By now, however, Lieutenant-Colonel Pearson was firmly in control of the 1st Battalion and there was no other vacancy in the Brigade for Hill to take over. Instead he was sent back to England where, out of regard for his dubious state of health, he was returned to a hospital in Tidworth. While he rested here he was offered the command of the 9th Parachute Battalion, which he eagerly accepted.

One of his first tasks as their commander was to take the Battalion out on a long march. Sergeant Woodcraft recalls: "At the end he addressed us, saying "Gentlemen, you are not fit, but don't let this worry you because from now one we are going to work a six and a half day week. You can have Saturday afternoons off!"". Hill was not joking in the slightest, even when his men attended Church on a Sunday morning, though their weapons were respectfully left outside they were all dressed in their full kit because James Hill would take them out on a march immediately afterwards.

Major Parry said of him, "The Colonel invariably picked on a different officer each day and said "Come along and walk to the office with me." The walk was a breathtaking experience. James Hill invariably carried a thumb stick, which increased the length of his stride. His speed of movement often left the unfortunate officer trotting a couple of paces behind his master, trying to answer his questions but with insufficient breath to do so. The Colonel quickly earned the name "Speedy" from the soldiers."

The 3rd Parachute Brigade had been raised by the much respected Brigadier Lathbury, but in April 1943, when the 6th Airborne Division was formed, Lathbury was sent to North Africa to take up command of the 1st Parachute Brigade. James Hill, as the most senior and experienced commander in the Brigade, was promoted to Brigadier and replaced him. Hill wrote "The brigade was made up of three county battalions. These battalions were invited to join the parachute brigade, and being good chaps they volunteered to a man. These chaps were the salt of the earth, prepared to give their lives without arguing the toss. They hadn't joined the army to parachute, but we said, 'Please parachute,' and they said, 'We'll try.'"

"During the physical training we focused on four objectives: speed, control, simplicity and fire effect. As parachutists we didn't carry much equipment, and we had to make use of this advantage to achieve great speed. If you could give orders twice as fast as anyone else you could gain ten minutes on the enemy. Coupled with speed was control - it was no good having expensive paratroops if they weren't under control. Simplicity was vital - the simpler things were, the fewer mistakes were made. Fire effect was essential because we didn't carry much ammunition, so every shot had to count. In order to achieve these four objectives we had to become amazingly fit. The initial training was extremely hard, and many of the volunteers left - they simply couldn't stand the pace of the training."

"We knew we would have to fight at night so we spent a great deal of time doing night-time training. For one week every month my brigade used to operate at night, sleeping during the daytime. Of course that was marvellous for all the chaps, but the poor brigade commander still had to spend the day doing administrative work! I was always keen for my brigade headquarters to do just as well as the chaps of the battalions, so on one occasion I took them for a two-hour march carrying 60 pounds of equipment. This of course included the clerks and the telephone operators! As we were staggering into the town of Bulford I was cheering them on, as you do, so that they would get to the end within the two hours. On the following Monday I received a notice saying that a deputation from the local Women's Institute wanted to see the brigade commander. They had come to complain about the way I had shouted at the chaps to finish - they thought it had been cruel and brutal. That rather amused me!"

"From January 1943 until D-Day in June 1944, we had to keep the chaps interested and on top form. One of the things I introduced in order to do that was parachuting dogs. A team of paratroops were trained in handling Alsatian messenger dogs. The dogs were given bicycle parachutes, as they were roughly the same weight as bicycles. The first time we took one of the dogs up he didn't want to jump, so we shoved him out. It turns out he enjoyed himself so much that the next time he couldn't wait to go! The dogs were trained to be messengers, but they were really just a sideshow to keep the men amused."

"At that time there were two fighter pilots who became known for being highly successful at shooting the enemy down at night - Cat's Eyes Cunningham and a chap called White Boycott, who had been at school with me. Rumour was that they were so good at night fighting because they ate a lot of carrots, and so we also ate carrots until we were quite sick of the things. I was lucky enough to have lunch with Cat's Eyes Cunningham recently, just before he died, and he told me that their success had nothing to do with eating carrots. The carrot story was just a ruse to prevent the enemy from finding out that they were equipped with the very latest form of radar."

"I wanted all of my brigade to go to church at least once a month, but some of the chaps didn't like this very much. So to motivate them I would make them carry 60 pounds of equipment to church, which they stacked up outside under guard before going inside. After the service I would take them for a 20-mile march. I thought that might motivate them to enjoy their time at church a bit more! The interesting thing is that, after D-Day, a number of people told me what a difference those church visits had made. When we were crossing the North Sea on D-Day it was a pretty rough night, and sitting in those planes were men of 22 who had never seen a shot fired in anger and were now flying into enemy territory. Up against something like that, even an atheist wants to pray."

"Napoleon said that 'the moral is to the physical as two is to one'. I found that if you are very fit, your morale is automatically good, and I put an awful lot of effort into getting the chaps extremely fit. It's amazing what a fit young body can take in the way of wounds and survive. The other thing that is important for morale is to be fighting a noble cause. I could not have fought for six years if I hadn't believed our cause to be completely right. I was asking those chaps to possibly die for the cause, I had to believe the cause to be true. I loved the men of my brigade, and if you love people they'll love you too, they'll follow you, and they'll have respect for you."

Towards the end of May 1944, when the 6th Airborne Division was being moved to its concentration areas, Brigadier Hill decided to place his Headquarters at RAF Down Ampney with the 1st Canadian Parachute Battalion. "I put my headquarters there because perhaps they were the least experienced of the chaps. It was amusing, I remember I used to have strict rules that everybody would be in their tents, and lights out by 10 o'clock. And then of course, a football would hit my tent. They weren't fussy!" On the 4th June, Hill gathered the officers of his Brigade around him for a final briefing. As proceedings were drawing to a close, he offered them some advice to remember during the first few hours of the drop, "Gentlemen, in spite of your excellent orders and training, DO NOT BE DAUNTED IF CHAOS REIGNS. It undoubtedly will."

"In camp, to keep the Canadians amused, I'd given them a football with Hitler's face on it in luminous paint. Everyone knew I was proposing to drop this, along with three bricks, which they had given me with some rather vulgar wording painted on them, on to the beach to astonish the enemy. So there I was, as brigade commander, standing in the door of the aeroplane with a football and three bricks!... Crossing The Channel, looking out, it was quite windy. There were a lot of sea horses all over the place and I remember thinking to myself that I had a good friend called Earl Prior Palmer who was commanding a swimming tank battalion and I thought God, how lucky I am to be in this aeroplane and not going in to battle on D-Day in a swimming tank... Then we came to the beaches, so I threw out my football (I like to imagine it bouncing up and down and when they went to retrieve it, the face of Hitler!), kicked the bricks out to drop, also on the beaches."

"There was flak all around. I don't think undue flak attending to our particular aircraft but plenty of it. So the red light was on and I was all ready." Moments later, Hill and the rest of his stick jumped. "I saw exactly where I was coming down, about a quarter of a mile from Cabourg, and I suppose about three miles from where I should have been... You orientate yourself and I remember it was a cloudy night but the moon was just coming through enough for me to do some orientating. To my horror I found myself dropping in to the flooded valley of the Dives... So in I went into 4½ feet of water. So you sort of re-organise yourself to the circumstances and I remember the first firing that I heard. I heard an exchange of shots and I was in the water. Then I found it was one member of my bodyguard shooting the other bodyguard in the leg by mistake. So that was an additional problem and, being a professional soldier, I had about 60 tea bags sewn in to the top of my battle dress trousers and of course, these tea bags did nothing but make tea and it took me 4 hours to get out of that water and I made cold tea all the time."

"The land had deep irrigation ditches and of course, if you're walking in water you can't see. We gradually gathered the chaps together. We realized we couldn't get on by ourselves... If one chap went down in one of those ditches, which were ten feet deep, of course with all your kit on you couldn't hope to get out... We all carried toggle ropes and everybody that I was able to pick up and collect, we all tied ourselves together with toggle ropes and that helped us. The other thing was the valley had been wired before it was flooded, so you would come up under water against wire barriers and on your own you couldn't get past them but if you walked out together with toggle ropes you could help each other... You got through them but the long and short of it was, 4 hours later we turned up on the edge of the flooded valley... I suppose about a quarter past six or something like that... and I had with me, collected and tied together, forty two chaps. So the first thing I did was to send the Canadians who were supposed to capture the dropping zone and capture the enemy principal headquarters on the edge of it and I sent for an officer to get hold of one to find out what the position was."

"I was able to contact the Company of the Canadian Battalion whose task it was to ensure the safety of the DZ, and who stated that they had captured the local German HQ there, but had not yet been able to winkle the enemy out of certain pillboxes on the perimeter... Then I thought what should I do now? I should be with my Brigade Headquarters on the ridge at four o'clock, and here it was at half past six and I was miles away, so I thought I'd go and see what had happened to the 9th Battalion. So I got hold of a party of very wet stragglers and we went on up towards where the 9th Battalion was, to find out if they'd been successful. My group was led by myself, my Defence Platoon Commander {Johnnie Jones} and one or two others, and we proceeded down a narrow path with water each side."

A little later the Royal Navy began to open fire on the British beaches, and Hill's party got a splendid view of its effect from on top of the ridge. "It was about twenty to seven when it started and I'd never seen such a barrage, which was coming from the sea to the land. It did look like the most glorious and superb firework display, which is once seen never forgotten."

At about the same time, Allied aircraft passed overhead and, mistaking Hill's party for the enemy, proceeded to attack them. "I had with me my brigade defence platoon commander, two parachute sailors who were part of our wireless link with the bombardment ship and one of our parachute Alsatian dogs, together with some thirty-five good chaps. We were making good progress and were encouraged by the tremendous din of the preliminary bombardment which the beach defences were undergoing. We were walking down a lane when I suddenly heard a horrible staccato sound approaching from the seaward side of the hedge... having in battle before, I knew exactly what that noise was... I shouted to everyone to fling themselves down and then we were caught in the middle of a pattern of anti-personnel bombs dropped by a large group of aircraft which appeared to be our own Spitfires... The lane had no ditches to speak of... We all threw ourselves down and I threw myself down on Lieutenant Peters who was the Mortar Officer of the 9th Battalion... While the fumes were dying away the first thought that crossed my mind was that this is the smell of death. I looked round and saw a leg beside me. I thought "My God, that's my leg." I knew I'd been hit. Then I had another look at it and it had a brown boot on it, and the only chap in the Brigade who was wearing a brown boot, strictly against my orders, was Lieutenant Peters. He'd got his boots I think in North Africa from the Americans. I had been saved because I had a towel and a spare pair of pants in the bottom of my jumping smock, but my water bottle had shattered and I had lost most of my left backside. After stumbling to my feet, I found one other man who was able to stand, namely my Defence Platoon Commander, and the lane was littered for many yards with the bodies of groaning and badly injured men. We looked around, saw nothing of Captain Robinson or anyone at the end, and presumed they may have been bombed as well."

"What did you do next? As a commander you either had two choices. You could sit up and patch up your chaps, or you can go on and do your job. So I had to go on and do my job. We took the morphia off the dead and gave it to those still living and injected them with their own morphia, and I suppose there was about a dozen people we did that to. That took us about half an hour. The thing I shall remember all my life is the cheer they gave us as we set off."

By about 10:00, Brigadier Hill and the remainder of his party reached the 9th Battalion's medical post. "I happened to bump into the Medical Officer who was a chap called Doc Watts, a splendid chap, older than most of the others. I think he was older than I was and I had a rule in the Brigade that nobody would parachute if they were thirty-two and over. He must have been among the ones who broke the rule. He was the only chap really of any consequence there, but I got the information I needed. The Doctor knew pretty well what was happening. Anyhow, he took a look at me and was unwise enough to say that I looked bad for morale. So I quickly cut him down to size and I told him what a bloody fellow he was, and if he'd had his left backside removed and spent four and a half hours in the cold water, he wouldn't look very good either! So that kept him quiet. He thought he'd better do something about this, so unbeknown to me he gave me an injection which put me out for two hours."

When Hill eventually regained consciousness he became aware that he could not walk. Furthermore, he had little idea how his Brigade was faring, and so he felt that it was vital that he should report to Divisional HQ for news. "Fortunately they found me a ladies' bicycle and I got a parachute pusher who pushed me down into Ranville, a distance of about two and a half miles, where I met General Gale and exchanged details. He told me the good news that my Brigade had taken all their objectives, so I thought that was heartening and I felt much younger!... I was seized by the ADMS {Colonel MacEwan} who was the Head Doctor, and he was an old boy of the Division, who'd been in the First World War and was covered in decorations. He said to me, "I'm going to take you off to the Main Dressing Station." I said, "You certainly aren't," and he said, "Well, you've got to have an op." So I said, "I'll have an op on one condition. As soon as it's over, you'll promise to take me back yourself to my Brigade Headquarters." So we struck a deal... It was about one o'clock and I was being anaesthetised, chloroform, or whatever it was... and I heard a tremendous concentration come down on Ranville, and that was in fact the counter-attack by 21st Panzer Division. So I rather wondered if, when I came to after my operation, who would be in charge of the hospital! After an hour or so I came to, and I looked round. They were still all our own medics."

As promised, Colonel MacEwan drove Hill to his Headquarters at Le Mesnil, however their trip was not without incident. "Just ahead of us, a number of Germans ran across the road and to my annoyance and consternation the ADMS and his batman left me in his jeep and pursued the Germans into the wood in an endeavour to make a capture. This effort was unsuccessful and at four o'clock that afternoon I reached my destination, some eight hours behind schedule." Once he had arrived, other medics insisted on checking Brigadier Hill's injury. Captain John Woodgate, the Brigade Administration Officer, believed that it may be necessary to evacuate him from the battlefield, but Hill told him in no uncertain terms that he was staying exactly where he was. To this end, Brigadier Hill used his authority as the Brigade Commander to forbid any operations to be carried out on him if their result would be his incapacitation. He did, however, consent to the alternative treatment, which proved successful, of taking large doses of anti-gas serum to prevent gas gangrene.

"Communication was obviously difficult on the day. My signaller had been dropped away from me, so until I got to brigade headquarters, my only means of communication was verbal. From headquarters I could keep an eye on the Canadians, and Terrence Ottway was just half a mile away. It was more difficult to communicate with Alistair Pearson of the 8th Battalion, who was about two miles down the road. But that was the parachuting game - it was part of our training to expect the unexpected. You knew exactly where you had to be and what you had to do, and if things went wrong you had to put them right personally. Our chaps showed great individuality and got themselves out of the most surprising predicaments, like being dropped behind enemy lines."

"I took stock that evening. {Lieutenant-Colonel} Alastair's {Pearson's} 8th Battalion was about 280 strong; the Canadian Battalion was in very good order and had captured their two bridges, and were now digging in at the Le Mesnil crossroads, about 300 men in all. The 9th Battalion, consisting of ninety good chaps, was still on the Le Plein feature. The only snag from my point of view was that they were supposed, that evening, to come into the Chateau {St Côme} which was part of our Brigade Defensive Plan. Of course, they didn't turn up, and the reason they didn't was that the Commandos, who were supposed to come and take over from them were held back at the bridge by General Richard Gale because the situation there was extremely uncertain and unstable. So he held them back there as a reserve. My Brigade Headquarters was depleted. I had no DAA and QMG, no Brigade Major and no Padre, no Commando Liaison Officer and no sailors. The two sailors who were to direct the guns of the Arethusa had been killed in the early bombing raid." Bill Collingwood, the Brigade Major, turned up on the 7th June, having landed with the 6th Airlanding Brigade after a terrifying experience the night before when he his parachute rigging became tangled up in the aircraft as he jumped, and he was dragged behind it for a full twenty minutes before being pulled back inside. "Collingwood arrived at Brigade HQ with his dislocated leg. I had him evacuated thirty-six hours later because I couldn't have a Brigade Major with his leg sticking out!".

"At the end of D-Day I was sitting at what I called my command post, on the steps leading up to a barn where I had my sleeping bag. Then, away to the south west, I suddenly saw hundreds of gliders coming in. It was the second wave of the 6th Airborne Division, gliding into battle. It was a wonderful sight. I knew they were carrying supplies, and the sight of them coming in to land made me feel less lonely, just as the sounds of the dawn battle had that morning. I said to myself, 'Remember all these things, because you're never going to see a sight like this again.' It was a great relief to know that we'd got to France, we had captured our objectives, and we were exactly where we were supposed to be. We knew we still had a fight on our hands, but we had landed. We had a little bit of France and those gliders coming in to land were following us. The battle started from there. Not with beautiful clean clothes and a nice map case, but worn out, wet, dirty and smelly."

Towards the end of the 7th June, the 9th Battalion were finally able to leave Le Plein and they made their way over to the Chateau St Côme. Due to their weak numbers they were unable to firmly defend the full area that they were to have occupied, instead Lieutenant-Colonel Otway consulted with Brigadier Hill and they agreed that the Battalion should concentrate in the Bois de Mont and attempt to deny the Chateau to the Germans through means of constant patrolling.

On the following day, the 8th June, the first of many serious attacks was made on the 3rd Parachute Brigade by the newly arrived 346th Division. Although all the attacks on this day were dealt with, the position of Brigade HQ at Le Mesnil became very difficult when it was heavily engaged by the enemy. Brigadier Hill felt the situation to be so serious that he established contact with Otway to request assistance from the 9th Battalion. Thirty men were sent and they succeeded in getting in behind the enemy, and between their own fire and that of Brigade HQ, the attack was broken.

"On the ridge we were fighting a top-ranking German division, 346 Panzer Grenadier Division. They had their own tanks, their own ak-ak guns - everything. But our chaps were tough. We started off with 2,200 men and ended up with about 700 at the most. We were able to see off a fresh infantry division with limited equipment, and the only reason we could do that was through sheer guts. As a brigade commander going into battle, you have a beautiful map case and sharp pencils, but there I was, minus half my backside, minus a pair of trousers, and all our chaps were in exactly the same boat. It was go, guts and gumption."

Although attacks were directed against many other elements in the 6th Airborne Division, in particular the 1st Special Service Brigade to the north, the main effort of the 346th Division was directed squarely towards the 3rd Parachute Brigade. Because of this, and also due to their weak numbers and the wide front for which they were responsible, the 5th Battalion The Black Watch were placed under Brigadier Hill's command on the 10th June. The Highlanders planned to attack and capture Bréville the following morning, but at this time the Chateau St Côme was still occupied by German troops. "I saw the CO {of the 5th Black Watch} and he said, "The only thing I want is the Chateau to be in our hands." I said, "OK, I'll ensure that the Chateau is freed." I remember going to Terence Otway and I gave him full marks for this one, and telling him that he had got to take the Chateau and make certain it was in our hands that evening, when the Black Watch wanted it. And I thought to myself, "Well really, here is a Battalion, absolutely whacked; they've had a hell of a time and now they've got to go and make certain via a strong patrol or company that they get the Chateau and hand it over to the Black Watch." And he {Otway} never belly-ached, he never blanched, he never did anything. He said, "OK"."

The Chateau was taken, however the attack on Bréville, mounted at first light on the 11th June, was a disaster as the Black Watch were quickly pinned down and forced to retire with approximately three-hundred casualties. Brigadier Hill ordered them to concentrate around the Chateau St Côme, close to the positions of the 9th Battalion. To the surprise of all in the Brigade, an enemy counterattack did not materialise that day, however on the 12th June, German guns pounded the 3rd Parachute Brigade's front and in the afternoon their infantry and armour mounted particularly heavy attacks. After much fighting the Black Watch were forced out of the Chateau and, low on ammunition and with the front line positions in some disarray, Lieutenant-Colonel Otway contacted Brigade HQ to request reinforcements. When he heard of this, Brigadier Hill knew at once that Otway must be in serious difficulty or else he would not have made such a report. "I had no spare bodies so I went to Colonel Bradbrooke {CO, 1st Canadian Parachute Battalion}, whose HQ was 200 yards away at the end of our drive and asked him to help. At that moment German tanks had overrun the road to his right and were shooting up his Company HQ at close range. To his eternal credit he decided that he could deal with this problem and he gave me what he had left of his Reserve Company under Major Hanson, a very hard and excellent commander, together with cooks and any spare men and we set off to the 9th Battalion's area. A young Red Indian aged eighteen, called Private Anderson, informed me that he was going to be my bodyguard."

Hill, with a pistol in one hand and his customary thumbstick in the other, personally led the Canadians of "C" Company forward. On the way his group was reinforced by sappers of the 3rd Parachute Squadron. When they arrived in the area they were confronted with the untidy situation of a woodland in fierce dispute between scattered pockets of the Black Watch and German infantry. With the Canadians at the front and the sappers following to their rear, the group fixed bayonets and moved into the woods. Jan de Vries of the 1st Canadian Parachute Battalion recalls: "In the run to the Chateau, as the noise of battle increased and with more shells and bullets flying around, I remember feeling not very heroic. But seeing the Brigadier totally exposed and urging us on gave me a feeling of resolve and let's get this over with." Brigadier Hill continues: "I was on the road and they {The Black Watch} had a very fine Padre {Tom Nicol}, a great big fellow, stood about six feet two inches, and he was calming these young chaps of the Black Watch, and of course they were in disarray here... We moved up to the far end of the wood near the Chateau and I remember seeing a German tank cruising up and down at close range but we had no means of dealing with it. At this stage my bodyguard had been shot through the arm but insisted on carrying on. However, by this time, the attack on both the Canadians and the 9th Battalion was petering out."

Leaving the Canadians to dig in and deal with the Germans to their front, Brigadier Hill turned back to find the sappers that he had left behind. Lance-Corporal Alan Graham of the 3rd Parachute Squadron recalls: "He personally, despite heavy small arms and mortar fire, guided our Troop to its defensive position to the forward area of a wood some fifty to seventy-five yards to the right of the Chateau. He left us with words of encouragement, and we quickly started digging our "shell scrapes"." Taking command of the battle from this forward position, Brigadier Hill learnt that the Germans were regrouping for another attack, and so he found the Forward Observation Officer, who brought the guns of two warships to bear, which did much to halt and disrupt the enemy's attempt to advance. By 20:00 the situation had been calmed to the point where Brigadier Hill felt able to return to his Headquarters at Le Mesnil, which he reached about an hour later. The position of his Brigade, however, was extremely fragile at this time and it was doubtful whether it could withstand another attack of this magnitude on the following day.

The decision to deal with the cause of the Brigade's troubles, the German occupation of Bréville, had already been taken, however. After consultation with Hill, Major-General Gale had come to the conclusion that afternoon that the village must be taken during the night, and at 21:45 a massive artillery bombardment began. At heavy cost, the 12th Parachute Battalion fought their way through the weakened Bréville garrison and took the village. With this pivotal position removed from the clutches of the 346th Division, the Germans had no effective platform through which to mount an attack upon the ridge, and moreover their offensive strength had been broken after the steady and devastating repulse of their many attacks over the last few days. Brigadier Hill's views on the matter were: "The German losses in both men and material were great and it would be said that we had won a great defensive victory."

James Hill continued to lead the 3rd Parachute Brigade throughout the remainder of the Normandy campaign, and for his efforts he was awarded a Bar to the Distinguished Service Order. His citation reads:

For conspicuous gallantry and devotion to duty from D Day until 1st September. Up to 11th June Brigadier Hill with three weak parachute battalions mustering approximately 1200 men held the important ridge from Chateau St Côme to the outskirts of Troarn. During this time he was repeatedly attacked by the 346 Division: the line at St Come was only held as a result of a brilliant and daring counter-attack by a company of Canadian Parachutists led by Brigadier Hill himself. From 11th June till 17th August his brigade was almost continuously in the line in the Le Mesnil cross-roads area. Here his example and personal courage directly contributed to the high state of morale which the troops under his command maintained. On the 17th August his brigade led the advance of the Division to Dozule. Under his leadership his brigade fought brilliantly and successfully at the Annebault ridge and again at Beuzeville. Throughout the whole period Brigadier Hill has shown an exceptionally high standard of gallantry and devotion to duty. He was wounded at the commencement of the campaign and although this wound often gave him considerable pain he never left his post.

In March 1945, the 6th Airborne Division took part in Operation Varsity, the Rhine Crossing. Brigadier Hill still commanded the 3rd Parachute Brigade at this time, and for his success as a commander and his conduct during the advance into Germany, he was awarded a third Distinguished Service Order:

Brigadier Hill has commanded 3 Parachute Brigade for two years. Throughout the campaign this officer has performed magnificent service. He has raised his Brigade to the very highest pitch of efficiency and fighting spirit.

In Normandy, in spite of being wounded himself and suffering heavy casualties in his brigade, every task set was successfully accomplished. The Brigadier showed the greatest gallantry throughout.

In the difficult conditions in the Ardennes and on the Maas, his unflagging enthusiasm kept his brigade at concert pitch. He was himself the inspiration of the vigorous offensive patrolling carried out across the River Maas.

In Germany Brigadier Hill rose to even greater heights. His men had a fine fighting start, in which, after suffering considerable casualties on landing, they utterly worsted the Germans and killed or captured a great number of them.

In the rapid advance which followed, his brigade gained even greater distinction. On three separate occasions they led the division over long distances into hostile country. Brigadier Hill was the dominant figure in these advances. Travelling well forward himself, showed an unquenchable determination to push on at whatever cost. This not only repeatedly surprised the enemy, but by rapid seizure of distant objectives saved our own troops many casualties. His brigade finished triumphantly by reaching the Baltic at 1400 hrs on 2nd May, after advancing 58 miles in one day.

Brigadier Hill's courage and dash in action are almost legendary. His skilful and inspiring leadership has been largely responsible for the great successes achieved by his Brigade.

After the war, Brigadier Hill was given command of the 4th Parachute Brigade of the Territorial Army, part of the 16th Airborne Division (TA). In June 2004, James Hill attended the 60th anniversary of the Normandy Landings in Normandy. Aged 93 at the time, he was the most senior ranking officer of the Normandy landings still alive. In that year a bronze bust in tribute to him was unveiled at Le Mesnil. James Hill died on the 16th March 2006, aged 95. His obituary in The Times reads as follows:

James Hill laid claim to being the longest-serving fighting brigade commander in the Second World War who was neither sacked nor promoted. He certainly appeared to have a brilliant further military career before him but, although originally a regular officer, he left the Army in 1945 to make his mark in commerce and industry. He also claimed the ornithological triumph of being only the second person to have found a cuckoo's egg in a whinchat's nest.

Stanley James Ledger Hill was the son of Major-General Walter P.H. Hill. He was educated at Marlborough and RMC Sandhurst, where he was captain of athletics and won the sword of honour. Commissioned into the Royal Fusiliers in 1931, when his father was colonel of the regiment, he ran the regimental athletic and boxing teams but transferred to the Supplementary Reserve in 1936 to marry, at what was then considered a very young age. Even so, such was his reputation that when he was recalled on the outbreak of war he was chosen to command the advance party of 2nd Battalion The Royal Fusiliers when they left for France in September 1939.

He commanded a platoon on the Maginot Line until appointed a staff captain at GHQ British Expeditionary Force in January 1940. When the German strategic attack was launched in May, he joined Lord Gort's command post during the battle of France, carried Gort's dispatches to Calais for withdrawal of the BEF and, in the final stage, took charge of the evacuation over the beach at La Panne.

On return to England he was awarded the Military Cross, promoted to major and travelled incognito to Dublin, at the request of the Irish Free State Government, to assist in planning for the evacuation of the city in the event of a German landing. The Germans were already busy on neutral territory - he discovered several staying with him at the Gresham Hotel.

He volunteered for parachute training and was appointed second-in-command of 1st Parachute Battalion on its formation on August 15, 1941. By the time this unit was launched on Operation Torch - the Allied invasion of French North Africa in November 1942 - Hill was in command. On November 15 the 32 Dakota aircraft carrying the battalion took off from Maison Blanche airfield in Algeria but met thick low cloud over Souk el Arba, the planned drop zone, making return the only option. Next day, having been ordered not to return a second time, Hill flew with the pilot of the leading Dakota, selected a DZ through a gap in the cloud using a ¼-inch-to-the-mile French motoring map and was the first man to jump. The battalion advanced briskly to Medjez el Bab, becoming the first Allied troops to engage the enemy in the Tunisian campaign. Hill was shot through the chest, neck and shoulder during an action on November 24 and evacuated to England. He was later awarded his first DSO.

Fit again by February 1943, he was promoted brigadier to raise and command the 3rd Parachute Brigade by converting three infantry battalions to the parachute role. One was later replaced by the 1st Canadian Parachute Battalion. As part of the 6th Airborne Division, this formation was to play a key role in the early hours of D-Day, the invasion of Normandy on June 6, 1944. Speaking after the war, Hill categorised the men under his command as either "soldiers of fortune" - spoiling for a fight and, in consequence, having to be very well disciplined, or as men who volunteered because they thought it their duty. Hill believed he needed to understand the make-up of each battalion exactly if he was to select the right one for every task from Normandy to the Baltic.

The D-Day tasks of 3rd Parachute Brigade were to silence the German artillery battery covering Sword beach from Merville 90 minutes before the first landing craft were due, demolish the bridges over the river Dives at Varaville, Robehomme, Bures and Troarn and then take and hold the high ground north of Troarn to Le Plein to prevent the enemy entering the bridgehead from the east. On the evening before D-Day they were confined to their camps, and Hill told his assembled officers and NCOs: "Gentlemen, in spite of your excellent training and orders, do not be daunted if chaos reigns. It undoubtedly will."

The valley of the Dives was interspersed with 4ft-deep irrigation ditches over much of the seven miles of the brigade front. Hill landed in one soon after midnight June 5-6. He gathered some of his brigade tactical headquarters together but was wounded soon afterwards by low-flying Allied aircraft dropping anti-personnel bombs in the wrong place.

Because of rough weather, poor visibility and instrument failure, men of the brigade were dropped over a far wider area than intended. Many drowned in areas flooded by the Dives but all objectives were taken and the ridge from Troarn to Le Plein was cleared of the enemy by the afternoon.

The battle to hold this ground, from which the enemy could dominate the crossings of the Orne, raged for two days and nights, after which Hill's brigade had lost 50 officers and 1,000 men

Having crossed the Seine by the end of September, 6th Airborne Division was withdrawn to be reinforced and retrained for further airborne operations. In the event Montgomery called for it to help plug the gap in the Allied front caused by Field Marshal von Runstedt's Ardennes offensive in December 1944. The division arrived by sea and reached the front in trucks but returned to England as soon as the offensive was regained. Their next task was to prepare for the Rhine crossing.

Ten thousand aircraft, including 540 Dakotas carrying parachute troops and 1,300 troop-carrying gliders, took part in the largest airborne operation of the war. Hill's brigade dropped on target and on time. The enemy was routed, but more than 1,000 men of the 6th Airborne Division were killed or wounded on March 24, 1945.

Thirty-seven days later, having fought its way across 275 miles of Germany, 3rd Parachute Brigade captured Wismar on the Baltic and became the first British troops to link up with the Russians advancing from the east.

Hill was awarded a Bar to his DSO for gallantry and leadership in Normandy and a second Bar for his service from the Rhine to the Baltic. He received the French Legion of Honour and the US Silver Star for his service in Tunisia and the northwest European campaign respectively. He was briefly military governor of Copenhagen after the liberation of the city in May 1945, then returned to civilian life.

As a Territorial Army officer he raised 4th Parachute Brigade TA in London and commanded it 1947-49. He was much involved in establishing the Parachute Regimental Association and was a trustee of the Airborne Forces Security Fund for 30 years and chairman for five.

He joined the board of Associated Coal and Wharf Companies in 1948 and was a director (1961-76) and vice-chairman (1970-76) of Powell Duffryn of Canada. He was chairman of Cory Brothers 1958-70, a director of Lloyds Bank 1972-79, chairman of Pauls & Whites of Ipswich 1973-76 and a member of Lloyds Banks (UK) Management Committee 1979-81. Bird watching was his principal recreation throughout his life.

He married, first, Denys, daughter of Hubert Gunter-Jones, in 1937 and, second, Joan Patricia Haywood, in 1986. He is survived by his second wife and a daughter from his first marriage.

Brigadier S.J.L. Hill DSO and two Bars, MC, wartime commander 3rd Parachute Brigade, was born on March 14, 1911. He died on March 16, 2006, aged 95.

For its terse, dramatic style, written by somebody who served with or under him and knew him well, this is unbeatable. Nothing has been altered, except for the font.

Brigadier Stanley James Ledger Hill, M.C. DSO x 3

"Speedy"

Service Number: 52648

Born: March 14th 1911 at Bath

Educated: Marlborough School

EARLY LIFE

Stanley James Ledger Hill was born in Bath on the 14th of March 1911. He attended Marlborough College where he headed the Officer Training Corps. He was the son of Major-General Walter Hill.

ENLISTMENT

James "Speedy" Hill joined the Army in 1930 and attended the Military Academy at Sandhurst where he excelled in all aspects of Military life. He was an outstanding athlete, and became the Captain of the athletics team there, and due primarily to his great strides when running was duly nicknamed "Speedy". He became a Sword of Honour recipient whilst at Sandhurst.

Commissioned into the 2nd Battalion The Royal Fusiliers where he continued his sporting prowess by running both the Athletics and Boxing teams. He was an active man who soon became disillusioned with the quiet mundane Military life of pre war England.

RESIGNATION

James Hill resigned his commission in early 1936 and worked for his families Ferry Company for three years, he stated he left the Army to get married, which he duly did in 1937 first, to Denys Gunter-Jones, with whom he had one daughter, and then latterly Joan Haywood.

OUTBREAK OF WAR

In 1939 at the outbreak of the Second World War James Hill re enlisted into his old Regiment and left for France as a Captain in the 2nd Battalion the Royal Fusiliers, advance Party. He led his platoon on the Maginot Line for two months before being posted to Army Headquarters as a staff captain.

In May 1940, James Hill was a member of Field Marshal Viscount Gort's command post, playing a leading part in the civilian evacuation of Brussels and La Panne beach during the final phase of the withdrawal. He returned to Dover in the last destroyer to leave Dunkirk, and was awarded an MC for his actions on the beachhead as rear guard.

PROMOTION

Following promotion to Major in 1940, he was posted to Northern Ireland. He was dispatched to Dublin to plan the evacuation of British nationals in the event of enemy landings in Southern Ireland, something that he had proven experience of carrying out effectively, following Dunkirk.

JOINED PARACHUTE REGIMENT

On the 15th of August, 1941, James Hill was one of the very first officers to join the newly formed Parachute Regiment, and in early 1942 took command of the 1st Battalion.

GUNSHOT WOUNDS

The Battalion's first operation was a parachute assault into Souk El Arba a small town, deep behind German lines in Tunisia. He had received orders to secure the area around the town which was flat so it could be used as an intended airstrip. Whilst there, he was commanded to take the remainder of his Battalion, 40 miles north east of the town to capture a vital rail link at Beja. This objective was to influence the French Garrison there that they should join the Allied cause. Hill carried out a strange tactic here to make the French change their minds and believe that Hill, had indeed a great Force under his command. He first made the Battalion don helmets and march through the main street, and then quickly out of sight, made them change into berets and do it again, influencing the French command structure of far greater Para numbers, and a side worth fighting alongside.

The Germans quickly got wind of the fact that there was a great Parachute Regiment Force at Beja, and responded by bombing the town. In response, Hill had learnt from a small reconnaissance party that the Germans and Italians had taken up residence in a small town called Gue further north of his location. Hill struck fast and furious in a legendary night attack, which was marred at the start by a serious accident. A grenade in a Royal Engineer's sack full of grenades went off prematurely, setting off the remainder, and ruining the surprise.

This killed and wounded many of the soldiers in the immediate area. The explosions alerted the German/Italian force who, manned their tanks and gun positions quickly in response.

Hill lead two companies on a frontal assault and whilst doing so decided to personally take out a number of tanks in line, still parked, but their crews still frantically taking up position within them. He took out his service pistol and thrust it through the open port hole and fired a single shot of the first tank, the Italian crew inside immediately surrendered. He then went to the second tank and tapped on the closed turret with the same result ... immediate surrender.

Thinking he was on a roll, he approached the third tank expecting surrender, only to be faced with a German tank crew who emerged firing their personal weapons and throwing grenades. Hill dispensed with the crew fairly quickly, but before doing so received three gunshot wounds to the chest.

For this action he received his first DSO Distinguished Service Order, his citation reads: For inspiring leadership and undaunted courage. This officer who led his Battalion after a flight of some 400 miles, and a parachute drop, displayed on every occasion conspicuous gallantry under heavy enemy fire. Leading his Battalion in raids against enemy A.F.V's he personally destroyed at least two and was mainly responsible for the successful results achieved. In a raid on an enemy post he led his Battalion forward under heavy machine gun fire and by his utter disregard of personal danger, and by his brilliant handling, was successful in entirely destroying the post and capturing a number of prisoners. This leadership and courage was an inspiration not only to his own troops but also to the French who recognised his gallantry by the award of the Legion d'honneur. On one occasion although severely wounded he continued to command his battalion until the successful completion of the operation.

HOSPITAL

He was rushed back to the Battalion Regimental Aid Post at Beja, where a Captain Robb of the 16th Parachute Field Ambulance operated on him and saved his life. He was evacuated to Algiers and then to England soon after.

LEGION d'HONNEUR

The citation for Hill's first DSO paid tribute to the brilliant handling of his force and his complete disregard of personal danger in this attack at Gue in Tunisia. The French who witnessed at first hand the bravery of this young fit officer, James Hill recognised his gallantry, by presenting him with the Legion d'Honneur.

ENGLAND AND RECOVERY

Whilst in hospital in England, Hill was told that he must rest and not carry out any exercise whilst his chest wounds recovered, but being the man that he had always been, an active athlete, he often exercised at night in the grounds of the hospital, having crept out of the ward window. It took him 2 months to recognise his fitness had returned and in December was discharged.

PARACHUTE REGIMENT CONVERSION

In December 1942 he was responsible for converting the 10th Battalion The Essex Regiment, into the 9th Parachute Battalion. In April 1943, Hill took command of the 3rd Parachute Brigade made up of the 8th and 9th Parachute Battalions and the 1st Canadian Parachute Battalion, which he later commanded on D-DAY as part of the 6th Airborne Division.

MERVILLE BATTERY

Hill was given overall command of the Merville Battery operation that our other Famous Face Lt Col Otway led so gallantly. Hill was also responsible for ensuring that a number of bridges were blown over the River Dives to prevent the Germans from bringing in reinforcements once the landings had commenced. Whilst briefing his officers for these attacks, his famous quote was "Gentlemen, in spite of your excellent training and orders, do not be daunted if chaos reigns. It undoubtedly will." And how right he was, especially with the poor deployment of both the Parachute drop and the Glider landings. Many of the beacons for the drop zones laid by the Pathfinders had been lost, so the intended DZ and LZ were either poorly lit or not lit at all, and a great number of the aircraft used on the assault had been hit or experienced technical faults.

BOMBED ACCIDENTLY BY ALLIED AIRCRAFT