The Peerage

One of the best things about developing a website is getting to understand things better – but it does have a downside, in that you feel compelled to pass this newfound knowledge on to your longsuffering public. Known technically as The Curse Of The Autodidact, it is best relegated to a subordinate link such as this.

In this case, of course, the self-educated body is best buried as deep as possible, because nobody, just nobody, not even God, because he has more pressing matters to attend to, can become fully conversant with, or keep abreast of, the English system of titles and honorifics relating to the Peerage – which could be defined as that fine body of men and women whose titles allow them to take their seats in the House of Lords ... although it's not as straightforward as it could be – for example:

- Ancestral titles still can't be inherited by women – for example, a duchess becomes a duchess solely by marriage to a duke, and not by inheriting her father's ducal title.

- Since the monumental bodge instituted by Prime Minister Blair, not all ancestral titles are now allowed to do so, as they failed some sort of beauty contest possibly suggested by Carol Caplin.

- In additional to the peerage, aka Lords Temporal in this context, the Anglican bishops and archbishops, aka Lords Spiritual, are also members of the House of Lords by right. Other religious leaders such as the Chief Rabbi are frequently ennobled as Life Peers, but it's by no means an automatic entitlement as far as I know.

Many hereditary titles over the years have been conferred for less than honourable reasons, such as turning a blind eye to the Monarch having his wicked way with your wife on a regular basis, or being the illegitimate fruit of such couplings. Others, particularly in the last century or two, have been handed out like cheap cigars at a coconut shy for long-term service in the House of Commons, or more fittingly for directing the affairs of the nation – Clement Attlee was the last Prime Minister to accept the traditional hereditary Earldom on retirement – but more recently such ennoblements have not been hereditary, and are called 'Life Peerages'.

There are also more dignified ways of acquiring a title, particularly by being born into the English Royal Family. But that adds several extra dimensions of complexity, particularly as regards the honorific of Prince (see later).

Let's start with the basics (and for further elaboration please follow the accompanying links to Wikipedia). The five tiers of peerage are as follows (but don't ask why the word "peer" means "equal" despite their being so blatantly disparate). The only ones with real cojones are dukes and earls (and to a lesser extent barons, though in modern accounts of more lawless times "the barons" is used as a collective term for those members of the aristocracy whose knuckles trailed the ground):

| Title | Spouse | Status | Origins |

| Duke | Duchess | Hered. | Originated from Latin dux, meaning military leader. Introduced by the Normans after 1066. |

| Marquess | Marchioness | Hered. | Derived from march, meaning a border area (cf Welsh marches) – complicated derivation from the French marquis. |

| Earl | Countess | Hered. | From the Anglo-Saxon jarl, meaning drinking companion of the king. |

| Viscount | Viscountess | Hered. | Originally a deputy Earl in mediaeval times. |

| Baron | Lady | Hered. | Introduced by Normans in 1066. Thuggish local chieftain. |

| Life | Male political appointee. | ||

| Baroness | n/a | Life | Female political appointee. |

| Baronet (not peer) | Lady | Hered. | Hereditary knighthood. |

| Knight (not peer) | Lady | Life | Ancient chivalric and martial title, but now earned by personal qualities and accomplishments. |

| Dame (not peeress) | n/a | Life | Modern female equivalent of Knight, earned by personal qualities and accomplishments. |

The titles in this table are in order of descending rank, or importance, corresponding to their order of precedence in a ceremonial procession, for example. There is also a minutely detailed protocol or etiquette of how they interleave with the dignitaries of other nations or cultures. It is said, for example, possibly apocryphally, that Debrett's§ once ruled that "The many millions of followers of His Highness the Aga Khan claim that he is directly descended from God – but an English Duke takes precedence."

§ Horses for courses, admittedly, but Debrett's and Who's Who aren't generally too much use for research into blue-blood history, as they both immediately edit-out an entry when he hands in his dinner pail. Burke's happily feature both the quick and the dead, I'm told, and so do my two altogether favourite resources for this purpose, Wikipedia and The Peerage – plus they're free!

Royal Dukes

Taking precedence over the common-or-garden dukes are the Royal Dukes, so-called as they are all close family of the monarch. The current Royal Dukedoms are, in order of precedence:

- Duke of Cornwall, held by Prince Charles, eldest son of the Queen

- Duke of Edinburgh, held by Prince Philip, husband of the Queen

- Duke of York, held by Prince Andrew, second son of the Queen

- Duke of Cambridge, held by Prince William, grandson of the Queen

- Duke of Gloucester, held by Prince Richard, cousin of the Queen

- Duke of Kent, held by Prince Edward, cousin of the Queen

Note that King George V had five sons, Edward VIII (Bad King, died sp), George VI (Good King, father of the Queen), then Prince Henry (father of Prince Richard D of G), then Prince George (killed in a plane-crash, father of Prince Edward D of K), then Prince John (who was kept in seclusion and died at the age of 13½).

- Note that the third son of the Queen, Prince Edward, is the Earl of Wessex (an ancient Kingdom of Saxon Britain) rather than the Duke of Somewhere. This is possibly to avoid confusion with the pre-existing Prince Edward the Duke of Kent.

- Note also that the Duke of Kent's younger brother Michael is designated as Prince Michael of Kent, although he is not the Royal Duke of Anywhere.

- Likewise, had the Duke of Gloucester's elder brother Prince William of Gloucester succeeded to their father's dukedom (instead of being killed in a plane-crash), the present Duke of Gloucester would likewise have been designated simply as Prince Richard of Gloucester, but not as the Duke of Anywhere.

There was of course also the Dukedom of Windsor, especially created for the appalling King Edward VIII, GVR's eldest son, after he abdicated. Fortunately he died without siring a male heir, and so the Dukedom was not perpetuated.

Princes

So what does the title of Prince actually mean? Millions of small girls need to know this, as their Daddy's car has a sticker saying "Princess on board", and they feel totally confident that one day their Prince will come to carry them off to his fairytale castle.

The short answer is "not a lot". It was introduced in 1714 at the insistence of the Elector of Hanover, who got seriously lucky and found himself invited over to England to become King George I, no need to learn the language, just listen to Herr Händel's nice Water Music from your Royal Barge.

But wait. After all, everybody's heard the story of the infant King Edward II, presented to the Welsh people by his father Edward I as their new Prince, "who spake not one word of English", and of the Black Prince of Wales (Edward, the eldest son of Edward III) for whom the dukedom of Cornwall was first created in 1337 – the earliest Dukedom in England – and who was the first (sic) hereditary Prince of Wales.

And indeed all first-born sons of English monarchs since then have been Princes of Wales. But the honorific term Prince seems to have been quite widely used simply as a generic reference to young male offspring of the monarch – as for example The Princes in The Tower.

Nowadays, it seems to be almost synonymous with Royal Dukes, all of whom are also designated as Princes. But (as mentioned above) not all Princes are Royal Dukes – Prince Edward Earl of Essex is not a Duke, and neither is Prince Michael of Kent.

The Gentry

It seems to me that this section of society had its origins in the mediaeval system of apprenticing the sons of noble families to other noble households, at the age of 7, to begin training for knighthood. At this stage they were called pages; they learned how to fight, how to use weapons, and how to ride a horse into battle. They also learned good manners and courteous speech from the nobleman's wife. At the age of 14 or 15, a page could become an esquire. Each esquire was assigned to a knight, though the knight could have several esquires. The esquire assisted the knight to whom he was assigned, as a shield-bearer (indeed the word esquire is a corruption of scutifer, from Latin scutum = shield and ferre = to carry) and armour-bearer at tournaments or in the prelude to a battle. He also continued to learn the art of swordplay and jousting, and the code of chivalry. By the age of about 20 or 21, and when he had proved himself in battle, and his knight felt he was ready, the esquire could become a knight himself.

Really, this was the early prototype of the modern progression from Home Counties mock-Tudor mansion to prep school, thence to public school, and finally passing Go on entry to the family firm. But in the late fifteenth century, the final stage of this process started to fall into desuetude. Firstly, the heavily-armoured knight on his massive charger had become increasingly ineffective militarily with the advent of crossbows and gunpowder. And secondly, the expense involved had become prohibitive anyway. So now many people simply walked away with the soubriquet of Esquire – it was evidence of good birth and upbringing, and that was all they needed – even if they didn't actually acquire a title.

And thus were born the landed gentry – people who were descended from titled forebears, and thereby had inherited a substantial estate, but were no longer actually titled themselves – except that the male line carried the appendage Esquire, rather like a Y chromosome.

Time passed, and estates were forfeited by riotous gambling or were inherited by an elder brother, but still the patina of gentility persisted. And so evolved just the straightforward, proud but impoverished, rural gentry – as would be recognised immediately by readers of Jane Austen.

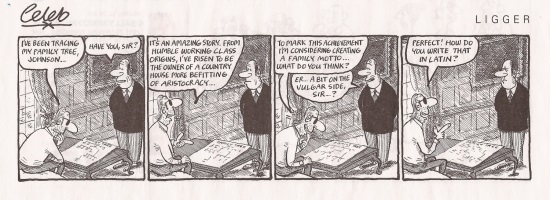

Or maybe, as in the case of John Halifax, Gentleman, long-forgotten hero of the mid-Victorian novelist Dinah Craik, a poor but almost repellently honest and sober young man who eventually bootstraps himself into a position of wealth and gentility, the process occurred in the opposite direction. This upward mobility (which of course has in reality been happening since much further back – think Dick Whittington!) nowadays occurs routinely for rock stars, premier league footballers, IT entrepreneurs, TV comedians and celebrity chefs, to all of whom the very idea of a social class deriving from mediaeval chivalry would be alien.

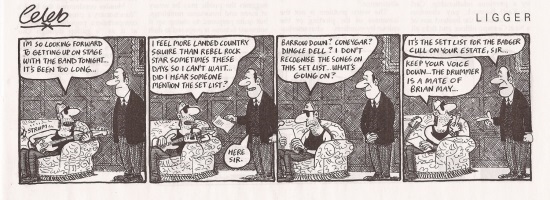

The two-tier concept of gentry – the esquires and the mere gentlemen – is now extinct, except in the phrases 'Old Money' and 'New Money', referring not to £sd as opposed to £.p but to inherited wealth (Good Family Background) versus newly-acquired riches (Nouveau Riche, Slightly Suspect) – think back to the classic BBC comedy To The Manor Born. And even those phrases and the attitudes they embody are obsolescent. We embrace the new elite of wealth and celebrity and see them as complementary to the genuinely aristocratic upper echelons of the Royal Family, in a seamless spectrum of glossiness in the pages of Hello! and OK! magazines.

But the title of squire – a corruption of esquire – has proved altogether more robust and enduring. Indeed the symbolic figure of John Bull, the archetypal Englishman, is the personification of this figure, conflated with the notion of Lord of the Manor. And the part played by squires in the hierarchy of village life right down to modern times has been a vital factor in the social cohesion of rural England during revolutionary times in the Napoleonic era and in the provision of food to desperately-underfed farm workers during the protracted agricultural depressions in Victorian times (see Jennifer Davies, The Victorian Kitchen, p 157, BBC Books, 1991).